Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (93 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

Major Schulze with the 3rd Battalion, 91st Mountain Jäger Regiment, stormed through the Bgalar Pass, and thus found himself immediately above the wooded slopes dropping steeply towards the coastal plain. The coast, the great objective, was a mere 12 miles away.

The Jägers had covered more than 120 miles of mountains and glaciers. With exceedingly weak forces they had fought engagements at altitudes of nearly 10,000 feet, overwhelming the enemy, charging vertiginous rocky ridges and windswept icy slopes and dangerous glaciers, clearing the enemy from positions considered impregnable. Now the men were within sight of their target. But they were unable to reach it.

Von Stettner's combat group had only two guns with twenty-five rounds each at its disposal for the decisive drive against the coast. "Send ammunition," he radioed. "Are there no aircraft? Aren't the Alpini coming with their mules?"

No—there were no aircraft. As for the Alpini Corps, they were marching to the Don, towards Stalingrad.

Colonel von Stettner, the commander of the gallant 91st Mountain Jäger Regiment, was in the Bzyb Valley, 12 miles from Sukhumi.

Major von Hirschfeld was in the Klydzh Valley, 25 miles from the coast.

Major-General Rupp's 97th Jäger Division had fought its way to within 30 miles of Tuapse. Included in this division were also the Walloon volunteers of the "Wallonie" Brigade under Lieutenant-Colonel Lucien Lippert.

But nowhere were the troops strong enough for the last decisive leap. Soviet resistance was too strong. The attacking formations of Army Group A had been weakened by weeks of heavy fighting, and supply lines had been stretched far in excess of any reasonable scale. The Luftwaffe had to divide its forces between the Don and the Caucasus. Suddenly the Soviet Air Force controlled the skies. Soviet artillery was enjoying superiority. The German forces lacked a few dozen fighter aircraft, half a dozen battalions, and a few hundred mules. Now that the decision was within arm's reach these vital elements were missing.

It was the same as on all other fronts: there were shortages everywhere. Wherever operations had reached culmination point and vital objectives all but attained, the German Armies suffered from the same fatal shortages. Before El Alamein, 60 miles from the Nile, Rommel was crying out for a few dozen aircraft to oppose British air power, and for a few hundred tanks with a few thousand tons of fuel. In the villages west of Stalingrad the assault companies of Sixth Army were begging for a few assault guns, for two or three fresh regiments with some anti-tank guns, assault engineers, and tanks. On the outskirts of Leningrad and in the approaches of Murmansk —everywhere the troops were crying out for that famous last battalion which had always decided the outcome of every battle.

But Hitler was unable to let any of the fronts have this last battalion. The war had grown too big for the Wehrmacht. Everywhere excessive demands were being made on the troops, and everywhere the fronts were dangerously over- extended.

The battlefields everywhere, from the Atlantic to the Volga and the Caucasus, were haunted by the spectre of impending disaster. Where would it strike first?

- Long-range Reconnaissance to Astrakhan

By armoured scout-car through 80 miles of enemy country— The unknown oil railway—Second Lieutenant Schliep telephones the station-master of Astrakhan—Captain Zagorodnyy's Cossacks.

IN the area of First Panzer Army, which formed the eastern part of Army Group A, the 16th Motorized Infantry Division was covering the exposed left flank by means of a chain of strongpoints.

The date was 13th September 1942, and the place was east of Elista in the Kalmyk steppe. "Hurry up and get ready, George—we're off in an hour!"

"Slushayu, gospodin Oberleutnant—yes, sir," shouted George the Cossack, and raced off. First Lieutenant Gottlieb was delighted with his eagerness.

George came from Krasnodar. He had learnt his German at the Teacher Training College there. In the previous autumn, while acting as a messenger, he had run straight into the arms of the motor-cyclists of 16th Motorized Infantry Division. Since then he had been doing all kinds of services for 2nd Company—first as assistant cook and later, after volunteering for the job, as interpreter. George had numerous good reasons for disliking Stalin's Bolshevism, and there was not a man in the company who did not trust him. In particularly critical situations George had even helped out as a machine-gunner.

Lieutenant Gottlieb had just returned from a conference with the Commander of Motor-cycle Battalion 165—the unit which later became Armoured Reconnaissance Battalion 116. There the last details had been discussed for a

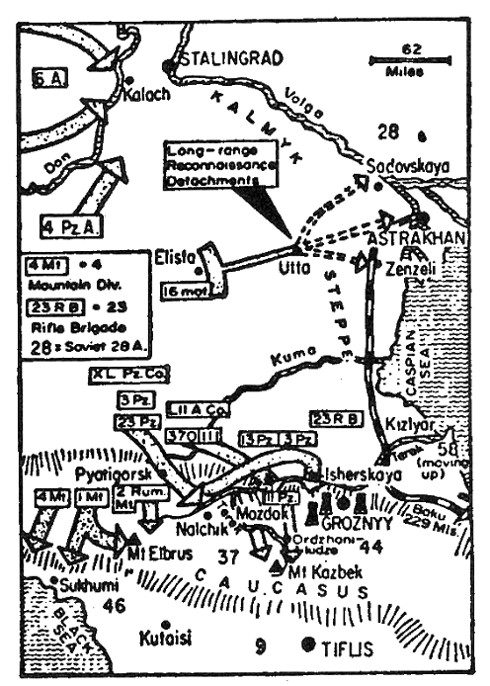

reconnaissance operation through the Kalmyk steppe to the Caspian. Lieutenant-General Henrici, commanding 16th Motorized Infantry Division, who had recently relieved LII Corps at Elista, wanted to know what was going on in the vast wilderness along the flank of the Caucasus front. Between the area south of Stalingrad and the Terek river, which 3rd Panzer Division had reached near Mozdok on 30th August with 394th Panzer Grenadier Regiment under Major Pape, there was a gap nearly 200 miles wide. Like a huge funnel this unknown territory extended between Volga and Terek, the base of the triangle being the coast of the Caspian. Any kind of surprise might come from there. That was why the area needed watching.

The task of guarding this huge no-man's-land had been assigned at the end of August to virtually a single German division—16th Motorized Infantry Division. It was based on Elista in the Kalmyk steppe. The actual surveillance and reconnaissance as far as the Caspian Sea and the Volga Delta was done, to begin with, by long-range reconnaissance formations. Reinforcements were not to be expected until the end of September, when Air Force General Felmy would bring up units under his Special Command "F."

It was then that the 16th Motorized Infantry Division earned its name of "Greyhound Division"—a name which the subsequent 16th Panzer Grenadier Division and, later still, 116th Panzer Division continued to bear with pride.

Apart from a few indispensable experts, the operation was mounted by volunteers alone. The first major expedition along both sides of the Elista-Astrakhan road was staged in mid-September. Four reconnaissance squads were employed. These were their tasks :

( 1 ) Reconnoitre whether any enemy forces were present in the gap between Terek and Volga, and if so where; whether the enemy was attempting to ferry troops across the Volga; which were his bases; and whether any troop movements were taking place along the riverside road between Stalingrad and Astrakhan.

(2) Supply detailed information on road conditions, the character of the coast of the Caspian Sea and the western bank of the Volga, as well as about the new, and as yet unknown, railway-line between Kizlyar and Astrakhan.

The force started out on Sunday, 13th September, at 0430 hours. A cutting wind was blowing from the steppe: it was going to be exceedingly cold until the sun broke through.

For their adventurous drive 90 miles deep into unknown, inhospitable enemy country the reconnaissance squads were appropriately equipped. Each squad had two eight-wheeled armoured scout cars with 2-cm. anti-aircraft guns, a motorcycle platoon of twenty-four men, two or three 5-cm. anti-tank guns—either self-propelled or mounted on armoured infantry carriers—and one engineer section with equipment. There were, moreover, five lorries—two each carrying fuel and water and one with food-supplies—as well as a repair and maintenance squad in jeeps. Finally, there was one medical vehicle with a doctor, and signallers, dispatch-riders, and interpreters.

Second Lieutenant Schroeder's reconnaissance squad had bad luck from the start. Shortly after setting out, just beyond Utta, the squad made contact with an enemy patrol. Second Lieutenant Schroeder was killed; Maresch, the interpreter, and Sergeant Weissmeier were wounded. The squad returned to base and set out again on the following day under the command of Second Lieutenant Euler.

Lieutenant Gottlieb, Second Lieutenant Schliep, and Second Lieutenant Hilger had meanwhile advanced with their own long-range reconnaissance squads to the north, to the south, and immediately along the great road from Elista to Astrakhan. Lieutenant Gottlieb, having advanced first along the road and then turned away north-east, into the steppe in the direction of Sadovskaya, had reached a point 25 miles from Astrakhan on 14th September. On 15th September he was within 15 miles of the Volga. From the high sand-dunes there was an open view all the way to the river. Sand and salt swamps made the ground almost impassable—but armoured reconnaissance squads invariably found a way.

The maps which Gottlieb had taken with him were not much good. At every well, therefore, George the Cossack had to engage in lengthy palavers with nomadic Kalmyks to find out about roads and tracks. These Kalmyks acted in a friendly way towards the Germans.

"The great railway? Yes—there are several trains each day between Kizlyar and Astrakhan."

Map 30.

The gap between the Caucasus front and Stalingrad was nearly 200 miles wide. Reconnaissance patrols of 16th Motorized Infantry Division got as far as the approaches of Astrakhan."And the Russkis?"

"Yes—they ride about a lot. Only yesterday a large number of them spent the night by the next well, about an hour's march to the east from here. They came from Sadovskaya. There must be a lot of them there."

"Really?" George nodded and gave the friendly nomad a few cigarettes.

Their laughter was abruptly cut short by a shout. One of them pointed to the north. Two horsemen were approaching at a gallop—Soviets.

The Kalmyks melted away. The two German armoured scout cars were behind a dune and not visible to the Russians.

Lieutenant Gottlieb called out to George: "Come back!" But the Cossack did not reply. He stuffed his forage-cap under his voluminous cloak, sat down on the well-head, and lit a cigarette.

Cautiously the two Russians approached—an officer and his groom. George called out something to them. The officer dismounted and walked up to him.

Lieutenant Gottlieb and his men could see the two talking and laughing together. They were standing next to each other. "The dirty dog," the wireless operator said. But just then they saw George quickly whip out his pistol. Clearly he was saying

"Ruki verkh"

because the Soviet officer put up his hands and was so much taken by surprise that he called out to his groom to surrender as well.Gottlieb's reconnaissance squad returned to Khalkhuta with two valuable prisoners.

Second Lieutenant Euler's special task was to find out exactly what the defences of Sadovskaya were like and whether any enemy troops were being ferried across the Volga in this area north of Astrakhan.

The distance from Utta to Sadovskaya, as the crow flew, was about 90 miles. Euler almost at once turned off the great road towards the north. After driving some six miles Euler suddenly caught his breath: a huge cloud of dust was making straight for his party at considerable speed. "Disperse vehicles!" he commanded. He raised his binoculars to his eyes. The cloud was approaching rapidly. Suddenly Euler started laughing. The force that was charging them was not Soviet armour, but a huge herd of antelopes, the sayga antelope which inhabits the steppe of Southern Russia. At last, getting scent of the human beings, they wheeled abruptly and galloped away to the east. Their hooves swept over the parched steppe grass, raising a cloud of dust as big as if an entire Panzer regiment were advancing across the endless plain.

Euler next reconnoitred towards the north-east and found the villages of Yusta and Khazyk strongly held by the enemy. He bypassed them, and then turned towards Sadovskaya, his principal target.

On 16th September Euler with his two armoured scout cars was within 3 miles of Sadovskaya, and thus only just over 4 miles from the lower Volga. The distance to Astrakhan was another 20 miles. Euler's reconnaissance squad probably got farthest east of any German unit in the course of Operation Barbarossa, and hence nearer than any other to Astrakhan, on the finishing-line of the war in the East.

What the reconnaissance squad established was of prime importance: the Russians had dug an anti-tank ditch around Sadovskaya and established a line of pillboxes in deep echelon.

This suggested a well-prepared bridgehead position, evidently designed to cover a planned Soviet crossing of the Lower Volga.

When the Russian sentries recognized the German scout cars wild panic broke out in their positions. The men, until then entirely care-free, raced to their pillboxes and firing-pits and put up a furious defensive fire with anti-tank rifles and heavy machine-guns. Two Russians, who raced across the approaches in the general confusion, were intercepted by Euler with his scout car. He put a burst in front of their feet.

"Ruki verkh!"Terrified, the two Red Army men surrendered—a staff officer of Machine-gun Battalion 36 and his runner. It was a rare catch.

Second Lieutenant Jürgen Schliep, the commander of the Armoured Scout Company of 16th Motorized Infantry Division, had likewise set out with his party on 13th September. His route was south of the main road. His chief task was to find out whether—as the interrogation of prisoners seemed to suggest—there was really a usable railway-line from Kizlyar to Astrakhan, though no such line was marked on any map. Information about this oil railway was most important, since it could be used also for troop transports.

Schliep found the railway. He recalls: "In the early morning of our second day out we saw the distant salt lakes glistening in the sun. The motor-cycles had great difficulty in negotiating the deep sand, and our two-man maintenance

team with their maintenance vehicle was kept busy with minor repairs."

When Schliep eventually spotted the railway-track through his binoculars he left the bulk of his combat group behind, and with his two scout cars and the engineer party drove on towards a linesman's hut. In fact, it was the station of Zenzeli.

Schliep's account continues: "From afar we saw fifty or sixty civilians working on the permanent way. It was a single- track line, protected along both sides by banks of sand. The men in charge of the party skedaddled the moment they saw us, but the rest of the civilian workers welcomed us with cheers. They were Ukrainian families—old men, women, and children—who had been forcibly evacuated from their homes and had been employed there on this work for the past few months. Many of the Ukrainians spoke German and hailed us as their liberators."

While the troops were talking to the Ukrainians a wisp of smoke suddenly appeared in the south. "A train," the workers shouted.

Schliep brought his scout car into position behind a sand-dune. An enormously long goods train, composed of oil and petrol tankers, was approaching with much puffing. It was hauled by two engines. Six rounds from the 2-cm. guns— and the locomotives went up. Steam hissed from their boilers and red-hot coal whirled through the air. The train was halted. And now one tanker wagon after another was set on fire.

"A damned shame—all that lovely fuel!" the gunners were grumbling. But the Ukrainians clapped their hands delightedly each time another tanker went up in flames. Finally the German engineers blew up the rails and the permanent way.

Just as they were getting ready to blow up the station shack the telephone rang. The engineers nearly jumped out of their skins. "Phew—that gave me quite a turn," said Sergeant Engh of the maintenance squad. But he quickly collected himself and shouted across to Schliep: "Herr Leutnant—telephone!"

Other books

Let Me Love You (Australian Sports Star Series Book 2) by Blobel, Iris

RESCUED BY THE RANCHER by Lane, Soraya

Amy, My Daughter by Mitch Winehouse

Breadfruit by Célestine Vaite

Into the Blue by Robert Goddard

Play With Me (Pleasure Playground) by Gayle, Eliza

Alien Tongues by M.L. Janes

The Best American Poetry 2015 by David Lehman

The Single Dad's Redemption by Roxanne Rustand

The Importance of Being Seven by Alexander Mccall Smith