Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (97 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

As 23rd August drew to its end the first German tank reached the high western bank of the Volga close to the suburb of Rynok. Nearly 300 feet high, the steep bank towered over the river, which was well over a mile wide at that point. The water looked dark from the top. Convoys of tugs and steamers were moving up and down stream. On the far bank glistened the Asian steppe, losing itself into infinity.

Near the river the division formed a hedgehog for the night, hard by the northern edge of the city. Right in the middle of the hedgehog were divisional headquarters. Wireless-sets hummed; runners came and went. All through the night work continued: positions were being built, mines laid, tanks and equipment serviced, refuelled, and restocked with ammunition for the next day's righting, for the battle for the industrial suburbs of Stalingrad North.

The men of 16th Panzer Division were confident of victory and proud of the day's successes; no one as yet suspected that these suburbs and their industrial enterprises would never be entirely conquered. No one suspected that just there, where the first shot had been fired in the battle of Stalingrad, the last one would be fired also.

The division no longer had any contact with the units following behind; the regiments of 3rd and 60th Motorized Infantry Divisions had not yet come up. That was hardly surprising, since Hübe's armoured thrust to the Volga had covered over 40 miles in a single day. The objective—the Volga— had been reached; all communications across the 40-mile-wide neck of land between Don and Volga had been cut. The Soviets had clearly been taken entirely by surprise by these developments. The division's positions came only under random artillery fire during the night. Maybe Stalingrad would fall the next day, dropping into Hübe's lap like a ripe plum.

- Battle in the Approaches

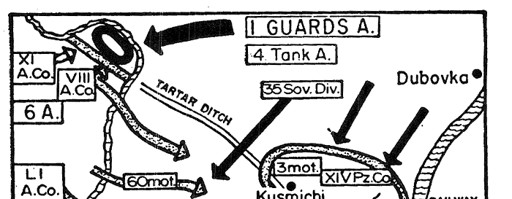

The Tartar Ditch-T-34s straight off the assembly line-Counterattack by the Soviet 35th

Division—Seydlitz's

Corps moves up-Insuperable Beketovka—Bold manœuvre by Hoth-Stalingrad's defences are torn open.ON 24th August, at 0440 hours, the Combat Group Krumpen launched its attack against Spartakovka, Stalingrad's most northerly industrial suburb, with tanks, grenadiers, artillery, engineers, and mortars, preceded by Stukas.

But the enemy they encountered was neither confused nor irresolute. On the contrary: the tanks and grenadiers were met by a tremendous fireworks. The suburb was heavily fortified, and every building barricaded. A dominating hill, known to the troops as "the big mushroom," was studded with pillboxes, machine-gun nests, and mortar emplacements. Rifle battalions and workers' militia from the Stalingrad factories, as well as units of the Soviet Sixty-second Army, were manning the defences. The Soviet defenders fought stubbornly for every inch of ground. The order which pinned them to their positions had said clearly: "Not a step back!"

The two men who saw that this order was ruthlessly implemented were Colonel-General Andrey Ivanovich Yeremenko, Commander-in-Chief Stalingrad and South-east Front, and his Political Commissar and Member of the Military Council, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev. It was then, over twenty years ago, that the officers of the 16th Panzer Division heard this name for the first time from Soviet prisoners.

With the forces available Spartakovka could clearly not be taken. The Soviet positions were impregnable. The determination displayed by the Soviets in holding their positions was further illustrated by the fact that they launched an attack against the northern flank of Hübe's "hedgehog" in order to relieve the pressure on Spartakovka. The Combat Groups Dörnemann and von Arenstorff were hard pressed to resist the increasingly vigorous Soviet attacks.

Brand-new T-34s, some of them still without paint and without gun-sights, attacked time and again. They were driven ofi the assembly line at the Dzerzhinskiy Tractor Works straight on to the battlefield, frequently crewed by factory workers. Some of these T-34s penetrated as far as the battle headquarters of 64th Panzer Grenadier Regiment and had to be knocked out at close quarters.

The only successful surprise coup was that by the engineers, artillery men, and Panzer Jägers of the Combat Group Strehlke in taking the landing-stage of the big railway ferry on the Volga and thereby cutting the connection from Kazakhstan via the Volga to Stalingrad and Moscow.

Strehlke's men dug in among the vineyards on the Volga bank. Large walnut-trees and Spanish chestnuts concealed their guns which they had brought into position against river traffic and against attempted landings from the far bank.

But in spite of all their successes the position of 16th Panzer Division was highly precarious. The Soviets were holding the approaches to the northern part of the city, and simultaneously, with fresh forces brought up from the Voronezh area, put pressure on the "hedgehog" formed by the division. Everything depended on securing the German corridor across the neck of land, and the 16th were therefore anxiously awaiting the arrival of 3rd Motorized Infantry Division.

The advanced units of that division had left the Don bridgeheads side by side.with 16th Panzer Division on 23rd August and moved off towards the east. At noon, however, their ways had parted. Whereas the 16th had continued towards the northern part of Stalingrad, Major-General Schlömer's regiments had fanned out towards the north in order to take up covering positions along the Tartar Ditch in the Kuzmichi area.

The general was moving ahead with the point battalion. Through his binoculars he could see goods trains being feverishly unloaded at Kilometre 564, west of Kuzmichi.

"Attack!"

The motor-cyclists and armoured fighting vehicles of Panzer Battalion 103 raced off. Gunners of Army Flak Battalion 312 sent over a few shells. The Russian columns dispersed.

The goods wagons contained a lot of useful things from America. These had been shipped across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, through the Persian Gulf, across the Caspian Sea, and up the Volga as far as Stalingrad, and thence by railway to the front, to the halt at Kilometre 564. Now these supplies were being gratefully received by Schlömer's 3rd Motorized Infantry Division—magnificent brand-new Ford lorries, crawler tractors, jeeps, workshop equipment, mines, and supplies for engineering troops.

The tanks of the advanced battalion had continued on their way when suddenly five T-34s appeared, evidently in order to recapture the precious gifts from the USA. Their 7'62-cm. shells quite literally dropped into the pea soup which was just being dished up for the division's operations section. The general and the chief of operations dropped their mess- tins and took cover. Fortunately two tanks of the point battalion had got stuck near the goods train with damaged tracks. They knocked out two of the T-34s and saved the situation. The remainder turned tail.

While Schlömer's formations were still following behind 16th Panzer Division more disaster loomed up; a Soviet Rifle Division, the 35th, reinforced with tanks, was driving down the neck of land from the north in forced marches. Its aim

— as revealed by the papers found on a captured courier—was to seal off the German bridgeheads over the Don and keep open the neck of land for the substantial forces which were to follow.

The Soviet 35th Division moved southward in the rear of the German 3rd Motorized Infantry Division; it over-ran the rearward sections of the two foremost divisions of von Wieter-sheim's Panzer Corps, forced its way between the bridgehead formed by the German VIII Infantry Corps and the German forces along the Tartar Ditch, and thereby prevented the German infantry, which was just then moving across the Don into the corridor, from closing up on the forces ahead of them.

As a result, the rearward communications of the two German lead divisions were cut off, and those divisions had to depend upon themselves. True, the 3rd Motorized Infantry Division and the 16th Panzer Division succeeded in linking up, but these two divisions now had to form a "hedgehog" 18 miles wide, extending from the Volga to the Tartar Ditch, in order to stand up to the Soviet attacks from all sides. Supplies had to be brought up by the Luftwaffe, or else escorted through the Soviet lines by strong Panzer convoys.

This unsatisfactory and critical situation persisted until 30th August. Then, at long last, the infantry formations of LI

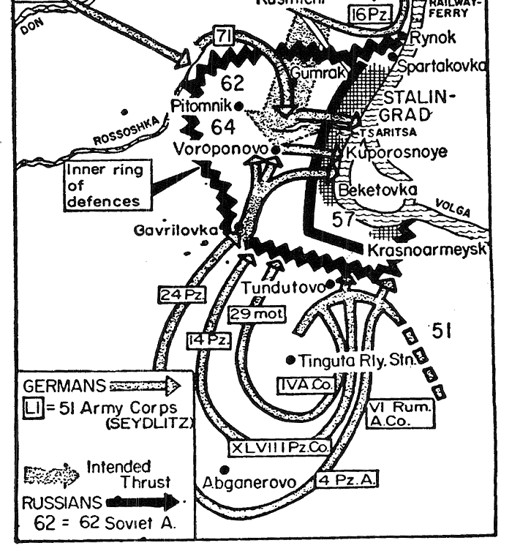

Corps under General of Artillery von Seydlitz moved up with two divisions on the right flank. The 60th Motorized Infantry Division likewise succeeded in insinuating itself into the corridor front after heavy fighting.

As a result, by the end of August, the neck of land between Don and Volga was sealed off to the north. The prerequisites had been created for a frontal attack on Stalingrad, and the outflanking drive by Hoth's Panzer Army from the south was now covered against any surprises from the northern flank.

General von Seydlitz-Kurzbach had been wearing the Oak Leaves to the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross since the spring of 1942. It was then that this outstanding commander of the Mecklenburg 12th Infantry Division had punched and gnawed his way through to the Demyansk pocket with his Corps group and freed Count Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt's six divisions from a deadly Soviet stranglehold.

That was why Hitler was again placing great hopes for the battle of Stalingrad on the personal bravery and tactical skill of this general, born in Hamburg-Eppendorf and bearing the name of an illustrious Prussian military family.

At the end of August Seydlitz launched his frontal attack against the centre of Stalingrad with two divisions striking across the neck of land from the middle of Sixth Army. His first objective was Gumrak, the airport of Stalingrad.

The infantry had a difficult time. The Soviet Sixty-second Army had established a strong and deep defensive belt along the steep valley of the Rossoshka river. These defences formed part of Stalingrad's inner belt of fortifications, which circled the city at a distance of 20 to 30 miles.

Until 2nd September Seydlitz was halted in front of this barrier. Then, suddenly, on 3rd September the Soviets withdrew, Seydlitz followed up, pierced the last Russian positions before the city, and on 7th September was east of Gumrak, only five miles from the edge of Stalingrad.

What had happened? What had induced the Russians to give up their inner and last belt of defences around Stalingrad and to surrender the approaches to the city? Had their troops suddenly caved in? Was the command no longer in control? Those were exciting possibilities.

There can be no doubt that this particular development in the battle of Stalingrad was of vital importance for the further course of operations. The events in this sector have not yet received adequate attention in German publications about Stalingrad—but the battle for the Volga metropolis certainly hung in the balance during these forty-eight hours of 2nd and 3rd September. The fate of the city appeared to be sealed.

Marshal Chuykov, then still a lieutenant-general and Deputy Commander-in-Chief Sixty-fourth Army, casts some light in his memoirs on the mystery of the sudden collapse of Russian opposition in the strong inner belt of fortifications along the Rossoshka stream. The solution is to be found in the actions and decisions of the two outstanding contestants in this mobile battle of Stalingrad—Hoth and Yeremenko.

Map 32.

On 30th August the Fourth Panzer Army tore open Stalingrad's inner belt of defences. Paulus's units were to have driven down from the north at the same time. But XIV Panzer Corps was tied down by enemy attacks. When Hoth's divisions linked up with 71st Infantry Division they were two days too late: the Russians had fallen back to the city outskirts at the last minute.Yeremenko, the bold and dashing, yet also strategically gifted Commander-in-Chief of the "Stalingrad Front" has revealed some interesting details of this great battle in his most recent publications. Chuykov's memoirs fill in many gaps and cast additional light on various aspects.

Colonel-General Hoth, Commander-in-Chief of the Fourth Panzer Army, now living in Goslar, where, before the war, he had served with the Goslar Rifle Regiment, just as Guderian and Rommel, has made available to the present author

his personal notes about the planning and execution of the offensive which brought about the collapse of the Soviet front.

At the end of July, Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army had wheeled away from the general direction of attack against the Caucasus and had been re-directed from the south through the Kalmyk steppe against the Volga bend south of Stalingrad. Its thrust was intended to relieve Paulus's Sixth Army, which even then was being hard pressed in the Don bend.

But once again the German High Command had contented itself with a half-measure. Hoth was approaching with only half his strength: one of his two Panzer Corps, the XL, had had to be left behind on the Caucasus front. His effective strength, in consequence, consisted only of Kempf s XLVIII Panzer Corps, with one Panzer and one motorized division, as well as von Schwedler's IV Corps, with three infantry divisions. Later, Hoth also received the 24th Panzer Division. The Rumanian VI Corps under Lieutenant-General Dragalina with four infantry divisions was subordinated to Hoth to protect his flank.

The Soviets instantly realized that Hoth's attack spelled the chief danger to Stalingrad. After all, his tanks were already across the Don, whereas Paulus's Sixth Army was still being pinned down west of the river by the Soviet defenders.

Other books

The China Study by T. Colin Campbell, Thomas M. Campbell

Forgotten Witness by Forster, Rebecca

Raven Flight by Juliet Marillier

Tiger Billionaire's Virgin Lover #1: Desires by Lynn, Michelle

Hip Deep in Dragons by Christina Westcott

Nightshifted by Cassie Alexander

Inherit the Stars by Tony Peak

The Fourth Man by K.O. Dahl

Siren Song by A C Warneke

Could I Have This Dance? by Harry Kraus