Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (99 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

In the morning of 16th September the situation again looked bad on Chuykov's city plan. The 24th Panzer Division had conquered the southern railway station, wheeled westward, and shattered the defences along the edge of the city and the hill with the barracks. Costly fighting continued on Mamayev Kurgan and at the main railway station.

Chuykov telephoned Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, Member of the Army Group's Military Council: "A few more

days of this kind of fighting and the Army will be finished. We have again run out of reserves. There is absolute need for two or three fresh divisions."

Khrushchev got on to Stalin. Stalin released two fully equipped crack formations from his personal reserve—a brigade of marines, all of them tough sailors from the northern coasts, and an armoured brigade. The armoured brigade was employed in the city centre around the main river port in order to hold open the supply pipeline of the front. The marines were employed in the southern city. These two formations prevented the front from collapsing on 17th September.

On the same day the German High Command transferred to Sixth Army the complete authority over all German formations engaged on the Stalingrad front. Thus the XLVIII Panzer Corps was detached from Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army and placed under General Paulus's command. Hitler was getting impatient: "This job's got to be finished: the city must finally be taken."

Why the city was not taken, even though the German tankmen, grenadiers, engineers, Panzer Jägers, and flak troops fought stubbornly for each building, is explained by the following figures. Thanks to Khrushchev's determined fight for the Red Army's last reserves, Chuykov received one division after another between 15th September and 3rd October—altogether six fresh and fully equipped infantry divisions. They were fully rested formations, two of them Guards divisions. All these forces were employed in the ruins of Stalingrad Centre and in the factories, workshops, and industrial settlements of Stalingrad North, which had all been turned into fortresses.

The German attack on the city was conducted, during the initial stage, with seven divisions—battle-weary formations, weakened by weeks of fighting between Don and Volga. At no stage were more than ten German divisions employed simultaneously in the fighting for the city.

True enough, even the once so vigorous Siberian Second Army was no longer quite so strong during the first phase of the battle. Its physical and moral strength had been diminished by costly operations and withdrawals. At the beginning of September it still consisted, on paper, of five divisions and five armoured and four rifle brigades—a total of roughly nine divisions. That sounds a lot, but the 38th Mechanized Brigade, for instance, was down to a mere 600 men and the 244th Rifle Division to a mere 1500—in other words, the effective strength of a regiment.

No wonder General Lopatin did not think it possible to defend Stalingrad with this Army, and instead proposed to surrender the city and withdraw behind the Volga. But determination counts for a great deal, and the fortunes of war, which so often follow the vigorous commander, have tipped the scales in more than one battle in the past.

By 1st October Chuykov, Lopatin's successor, already had eleven divisions and nine brigades—

i.e.,

roughly fifteen and a half divisions—not counting Workers' Guards and militia formations.On the other hand, the Germans enjoyed superiority in the air. General Fiebig's well-tried VIII Air Corps flew an average of 1000 missions a day. Chuykov in his memoirs time and again emphasizes the disastrous effect which the German Stukas and fighter-bombers had upon the defenders. Concentrations for counter-attack were smashed, road- blocks shattered, communication lines severed, and headquarters levelled to the ground.

But what use were the successes of the "flying artillery" if the infantry was too weak to break the last resistance? Admittedly the Sixth Army was able, following the settling down of the situation on the Don, to pull out the 305th Infantry Division and to use it later for relieving one of the worn-out divisions of LI Army Corps. But General Paulus did not receive a single fresh division. With the exception of five engineer battalions, flown out from Germany, all the replacements he received for his bled-white regiments had to come from within the Army's zone of operations. In the autumn of 1942 the German High Command had no reserves whatever left on the entire Eastern Front. Serious crises had begun to loom up in the areas of all the Army Groups from Leningrad down to the Caucasus.

In the north Field-Marshal von Manstein was compelled to use the bulk of his former Crimean divisions for counterattacks against Soviet forces which had penetrated deeply into the German front. After fierce defensive fighting on the Volkhov, continuing until 2nd October, Army Group North was forced to gain a little breathing-space for itself in the first battle of Lake Ladoga.

In the Sychevka—Rzhev area Colonel-General Model had to employ all his skill and all his forces in order to ward off Russian break-through attempts. He had to stand up to three Soviet Armies.

In the centre and on the southern wing of the Central Front, Field-Marshal von Kluge likewise had to employ all his forces to prevent a break-through towards Smolensk.

In the passes of the Caucasus and on the Terek, finally, the Armies of Army Group A were engaged in a desperate race against the threatening winter, trying once more, with a supreme effort, to get through to the Black Sea coast and the oilfields of Baku.

In France, Belgium, and Holland, on the other hand, there were a good many divisions. They spent their time playing cards. Hitler, who persistently under-rated the Russians, made the opposite mistake of over-rating the Western Allies. Already, in the autumn of 1942, he feared an Allied invasion. The American, British, and Soviet secret services nurtured his fear by clever rumours about a second front. The skilfully launched spectre of an invasion which was not to materialize for another twenty months was already tying down twenty-nine German divisions, including the magnificently equipped "Leibstandarte" and the 6th and 7th Panzer Divisions. Twenty-nine divisions! A quarter of them might have turned the tide on the Stalingrad-Caucasus front.

- Last Front Line along the Cliff

Chuykov's escape from the underground passage near the Tsaritsa—The southern city in German hands-The secret of Stalingrad: the steep river-bank-The grain elevator-The bread factory—The "tennis racket"-Nine-tenths of the city in German hands.

DURING the night of 17th/18th September Chuykov had to clear out of his bomb-proof shelter near the Tsaritsa. It was virtually a flight, for grenadiers of the Lower Saxon 71st Infantry Division, the division with the clover-leaf for its tactical sign, suddenly appeared at the Pushkin Street entrance to the dug-out towards noon. Chuykov's staff officers had to grab their machine pistols. The underground gallery was rapidly filling with wounded and with men who had become separated from their units. Drivers, runners, and officers smuggled their way into the safety of the dug-out under all kinds of pretexts, "in order to discuss urgent matters." As the underground passages had no ventilation system they were soon filled with smoke, heat, and stench. There was only one thing to do—get out.

The headquarters guard covered the retreat by way of the second exit, into the Tsaritsa gorge. But even there German assault parties of Major Fredebold's 191st Infantry Regiment were already in evidence. Carrying only his most important papers and the situation map, Chuykov surreptitiously made his way through the German lines to the Volga bank, through the night and the fog, and together with Krylov crossed to the eastern side by boat.

Chuykov at once boarded an armoured cutter and recrossed the Volga to the upper landing-stage in the northern city. There he established his battle headquarters in the steep cliff towering above the river, behind the "Red Barricade" ordnance factory—a few caves blasted into the 650-foot-high bluff in the blind angle of the German artillery. The various dug-outs were linked by well-camouflaged communication trenches in the steep scarp.

Glinka's kitchen was accommodated in the inspection shaft of the effluent tunnel of the "Red Barricade" works. Tasya, the serving-girl, had to perform real acrobatics dragging her pots and pans up the steel ladder of the shaft into the daylight and then balancing them down a cat-walk along the cliff-face into the Commander-in-Chief's dug-out.

Admittedly, the number of mouths to be fed at headquarters had greatly diminished. Various senior officers, including Chuykov's deputies for artillery and engineering troops, for armour and for mechanized troops, had slipped away quietly during the move of headquarters and had stayed behind on the left bank of the Volga. "We shed no tears over them," Chuykov records. "The air was cleaner without them."

The move which the C-in-C Stalingrad had to perform was symbolical: the focus of the fighting was shifting to the north. The southern and central parts of the city could no longer be held.

On 22nd September the curtain went up over the last act in the southern city. Assault parties of 29th Motorized Infantry Division, together with grenadiers of 94th Infantry Division and the 14th Panzer Division, stormed the smoke- blackened grain elevator. When engineers blasted open the entrances a handful of Soviet marines of a machine-gun platoon under Sergeant Andrey Khozyaynov came reeling out into captivity, half insane with thirst. They were the last survivors.

Men of the 2nd Battalion of the Soviet 35th Guards Division were lying about the ruins of the concrete block— suffocated, burnt to death, torn to pieces. The doors had been bricked up: in this way the commander and commissar had made all retreat or escape impossible.

The southern landing-stage of the Volga ferry was likewise occupied. Grenadiers of the Saxon 94th Infantry Division under Lieutenant-General Pfeiffer, the division whose tactical sign was the crossed swords found on Meissen porcelain, took over cover duty along the Volga bank on the southern edge of the city.

In Stalingrad Centre, in the heart of the city, Soviet opposition also crumbled. Only a few fanatical nests of resistance, manned by remnants of the Soviet 34th and 42nd Rifle Regiments, were holding out among the debris of the main railway station and along the landing-stage of the big steam ferry in the central river-port.

By 27th September—applying the customary criteria of street fighting—Stalingrad could be said to have been conquered. The 71st Infantry Division, for example, had reached the Volga over the division's entire width—211th Infantry Regiment south of the Minina gorge, 191st Infantry Regiment between the Minina and Tsaritsa gorges, and 194th Infantry Regiment north of the Tsaritsa.

The fighting now centred on the northern part of the city with its workers' settlements and industrial enterprises. The names have gone down not only in the history of this war, but in world history generally—the "Red Barricade" ordnance factory, the "Red October" metallurgical works, the "Dzer-zhinskiy" tractor works, the "Lazur" chemical works with its notorious "tennis racket," as the factory's railway sidings were called because of their shape. These were the "forts" of the industrial city of Stalingrad.

The fighting for Stalingrad North was the fiercest and the most costly of the whole war. For determination, concentration of fire, and high density of troops within a very small area these operations are comparable only to the great battles of material of World War I, in particular the battle of Verdun, where more than half a million German and French troops were killed during six months in 1916. The battle in Stalingrad North was hand-to-hand fighting. The Russians, who were better at defensive fighting than the Germans anyway, benefited from their superior possibilities of camouflage and from the skilful use of their home ground. Besides, they were more experienced and better trained in street fighting and barricade fighting than the German troops. Finally, Chuykov was operating right under Khrushchev's eyes, and therefore he whipped up Soviet resistance to red heat. As each company crossed the Volga into Stalingrad three slogans were impressed on it:

Every man a fortress!

There's no ground left behind the Volga! Fight or die!

This was total war. This was the implementation of the slogan "Time is blood." The chronicler of 14th Panzer Division, Rolf Grams, then a major commanding Motor-cycle Battalion 64, quotes a very illuminating account of an engagement: "It was an uncanny, enervating battle above and below ground, in the ruins, the cellars, and the sewers of the great city and industrial enterprises—a battle of man against man. Tanks clambering over mountains of debris and scrap, crunching through chaotically destroyed workshops, firing at point-blank range into rubble-filled streets and narrow factory courtyards. . . . But all that would have been bearable. What was worse were the deep ravines of weathered sandstone dropping sheer down to the Volga, from where the Soviets would throw ever new forces into the fighting. Across the river, in the thick forests of the lower, eastern bank of the river, the enemy lurked invisible, his batteries and his infantry hidden from sight. But he was there nevertheless, firing, and night after night, in hundreds of boats across the river, sending reinforcements into the ruins of the city."

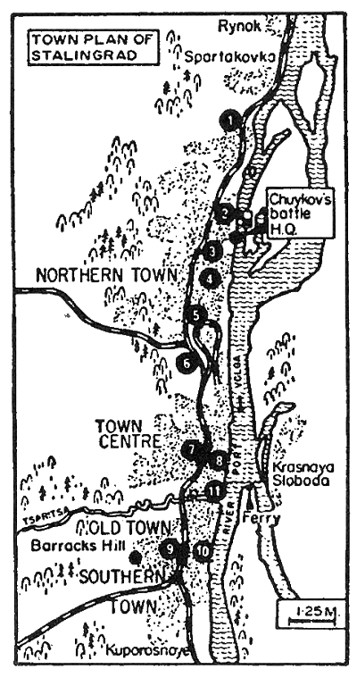

Map 33.

1 Tractor works; 2 "Red Barricade" ordnance factory; 3 bread factory; 4 "Red October" metallurgical works; 5 "Lazur" chemical works with "tennis racket" sidings; 6 Mamayev Kurgan hill; 7 central railway station; 8 Red Square with department store; 9 southern railway station; 10 grain elevator; 11 Chuykov's dugout in the Tsaritsa gorge.These Soviet supplies flowing in steadily across the river to buttress the defenders, this fresh blood continually pumped into the city through the vital artery that was the Volga— these constituted the key problem of the battle. The key to it all was in the weathered sandstone gorges of the Volga bank. The steep bluff, out of reach of the German artillery, contained the Soviet headquarters, the field hospitals, the ammunition dumps. Here were ideal assembly points for the

shipments of men and material across the river at night. Here were the starting-lines for counter-attacks. Here the tunnels carrying the industrial sewage emerged on the surface—now empty underground galleries leading into the rear of the German front. Soviet assault parties would creep through them. Cautiously they would lift a manhole cover and get a machine-gun into position. Suddenly their bursts of fire would sweep the rear of the advancing German formations, mowing down cookhouse parties and supply columns. A moment later the manhole covers would drop back into place and the Soviet assault parties would have vanished.

German assault troops assigned to deal with such ambushes were helpless. The steep western bank of the Volga was worth as much as a deeply echeloned bomb-proof belt of fortifications. Frequently only a few hundred yards divided the German regiments in their operations sectors from the Volga bank.

General Doerr in his essay on the fighting in Stalingrad observes quite correctly: "It was the last hundred yards before the Volga which held the decision both for attacker and defender."

The way to this vital bank in Stalingrad North led through the fortified workers' settlements and industrial buildings. They formed a barrier in front of the vital steep bank. It would take an entire chapter to describe these operations. A few typical examples will testify to the heroism displayed on both sides.

At the end of September General Paulus tried to storm the last bulwarks of Stalingrad, one after another, by a concentrated assault. But his forces were insufficient for an all-embracing large-scale attack on the entire industrial area.

The well-tried 24th Panzer Division from East Prussia, advancing from the south across the airfield, stormed the "Red October" and "Red Barricade" housing estates. The Panzer Regiment and units of 389th Infantry Division also captured the housing estate of the "Dzerzhinskiy" tractor works, and on 18th October fought their way into the brickworks. The East Prussians had thus reached the steep Volga bank. In this sector, at least, the objective had been attained. The division then moved south again into the area of the "Lazur" chemical works and the "tennis racket" railway sidings.

The 24th had tackled their task—but at what cost! Each of the grenadier regiments was just about large enough to make a battalion, and the remnants of the Panzer Regiment were no more than a reinforced company of armoured fighting vehicles. Those crews without tanks were employed as rifle companies.

The huge "Dzerzhinskiy" tractor works, one of the biggest tank-manufacturing enterprises in the Soviet Union, was stormed on 14th October by General Jaenecke's 389th Infantry Division from Hesse and by the regiments of the Saxon 14th Panzer Division. Across the debris of the vast factory grounds the tanks and grenadiers of the 14th drove through to the Volga bank, wheeled south, penetrated into the "Red Barricade" ordnance factory, and thus found themselves immediately in front of the steep bank close to Chuykov's battle headquarters.

The ruins of the gigantic assembly buildings of the tractor plant, where Soviet resistance kept flaring up time and again, were gradually being captured by battalions of the 305th Infantry Division from Baden-Württemberg, the Lake Constance Division, which had been brought from the Don front on 15th October to be employed against Stalingrad's tractor plant. The men from Lake Constance were engaged in protracted fighting with companies of the Soviet 308th Rifle Division under Colonel Gurtyev. The operation was a perfect illustration of General Chuykov's remark in his diary: "The General Staff map is now replaced by the street plan of part of the city, by a sketch plan of the labyrinth of masonry that used to be a factory."

On 24th October the 14th Panzer Division reached its objective—the bread factory at the southern corner of the "Red Barricade." The Motor-cycle Battalion 64 was heading the attack. On the first day of the fighting Captain Sauvant supported the assault on the first building with units of his 36th Panzer Regiment.

On 25th October the attack on the second building collapsed in the fierce defensive fire of the Russians. Sergeant Esser was crouching behind a wrecked armoured car. Across the road, at the corner of the building, lay the company commander—dead. Ten paces behind him the platoon commander —also dead. By his side a section leader was groaning softly —delirious with a bullet through his head.

Quite suddenly Esser went berserk. He leapt to his feet. "Forward!" he screamed. And the platoon followed him. It was some 60-odd yards to the building—60 yards of flat courtyard without any cover. But they made it. Panting, they flung themselves down alongside the wall, they blasted a hole into it with an explosive charge, they crawled through, and they were inside. At the windows across the room crouched the Russians, firing into the courtyard. They never realized what was happening to them when the machine pistols barked out behind them: they just slumped over.

Other books

The Huntress by Michelle O'Leary

Venus in Furs by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch

Filthy Gorgeous Lies: Book 1 by Sophie Night

Pretty is as Pretty Dies (A Myrtle Clover Mystery) by Elizabeth Spann Craig

Under the Never Sky by Veronica Rossi

Beauty by Daily, Lisa

Temptation at Twilight: Lords of Pleasure by Carlisle, Jo

William Falkland 01 - The Royalist by S.J. Deas

The Seventh Sister, A Paranormal Romance by Z L Arkadie