How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (23 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

“Well, eight and three

do

make eleven, dear,” one of the women told her, and instead of becoming angry Sophia threw back her head and laughed.

do

make eleven, dear,” one of the women told her, and instead of becoming angry Sophia threw back her head and laughed.

“Sara, you were right after all,” she called to the back of the room, where Sara perched quietly on the staircase. “Let's go back up and practice numbers some more.” In the manner of well-raised children in company, Sophia curtsied to the grown-ups before she turned to leave the room.

“Is Sara your sister, dear?” the woman asked. Before Sophia could answer, her mother said sharply, “Oh, no, not at all. She's the daughter of one of the servants. We sometimes allow her to play with Sophia, however.”

“How

democratic

of you, Margaret,” the woman said, and back on the staircase I saw Sara's cheeks flush bright red before she turned and followed her friend Sophia. So, along with intelligence and ambition she also had pride.

democratic

of you, Margaret,” the woman said, and back on the staircase I saw Sara's cheeks flush bright red before she turned and followed her friend Sophia. So, along with intelligence and ambition she also had pride.

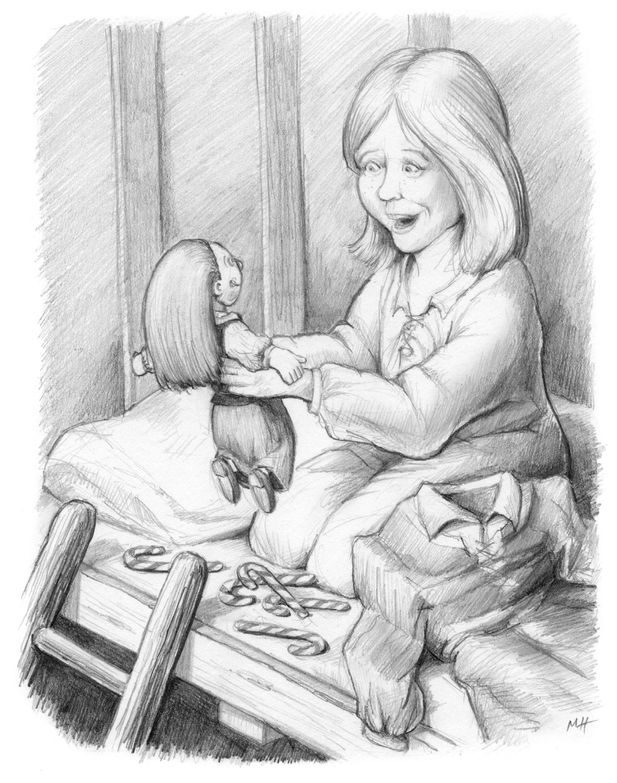

So eight-year-old Sara woke up on the morning of December 25, 1642, to discover a dress and a doll by her pallet, as well as several candy canes on her pillow. She shrieked with delight, trying to pull the dress on over her nightgown while cuddling the doll at the same time.

CHAPTER

Thirteen

Thirteen

Â

Â

Â

Â

T

hat night, Elizabeth asked if I would take Sara home. She explained she'd just heard a friend was about to give birth, and needed to go to her and help with the delivery of the baby. While rich women brought their babies into the world surrounded by physicians and midwives, poor women usually had to rely on their friends. I told Elizabeth I'd be glad to, and went upstairs to fetch Sara from Sophia's bedroom. I found the girls sprawled on a wide bed with silk covers and a canopy. Sophia was talking about a dress her father had promised to buy her, and Sara was bent over a slate, studying arithmetic.

hat night, Elizabeth asked if I would take Sara home. She explained she'd just heard a friend was about to give birth, and needed to go to her and help with the delivery of the baby. While rich women brought their babies into the world surrounded by physicians and midwives, poor women usually had to rely on their friends. I told Elizabeth I'd be glad to, and went upstairs to fetch Sara from Sophia's bedroom. I found the girls sprawled on a wide bed with silk covers and a canopy. Sophia was talking about a dress her father had promised to buy her, and Sara was bent over a slate, studying arithmetic.

“Time to go home, Sara,” I interrupted. “Your mother has to go help a friend, so it will be just you and me.”

“You're Sara's Aunt Layla, aren't you?” Sophia inquired. “The one who's come to stay at her house while your husband's in the colonies? Do you like living with Sara and her mother? How long do you expect to stay with them?”

“I really don't know,” I replied, trying to sound respectful as befitted a servant speaking to an employer's child. “I'm just glad Sara and her mother have offered me their hospitality.”

“Sara says she likes you,” Sophia observed, and I felt immensely pleased to hear it, though Sara had never said anything to me that indicated like or dislike, for that matter. “She's glad you're her aunt.”

“I'm glad, too,” I said, and Sara and I set out for the cottage. Since it was just the two of us, I thought the girl might chat with me along the way, but she didn't. We walked in companionable silence though. I found pleasure simply in her presence. It occurred to me that, although Nicholas and I and the rest of the companions had devoted our lives to children, we never actually spent time with them besides briefly coming into their homes at night to leave holiday gifts.

When we reached the cottage we went inside and lit some candles. Today, with electric lights that shine brightly at the touch of a switch, that Canterbury cottage in 1642 would probably seem like a dark, depressing place. But back then, a few candles and their meager light were what we were used to, and so Sara and I found their glow cheerful. Neither of us had eaten, so she fetched water and I sliced bread and washed a few carrots and pears. As we ate our simple meal I asked, “What cities do you want to visit someday?”

“Paris,” Sara said promptly. “Athens, in Greece. Rome, of course, and Alexandria. I suppose I'll start with London, since it's the nearest great capital and I haven't even been there, yet. What is it like?”

I told her about the high towers and palaces, the great hall of Parliament, and the other impressive buildings. Then I described London Bridge over the wide Thames, and the marketplaces where so many things were for sale, and the theaters and gardens and the streets with cobblestones. I did leave out details about trash and smells, because this little girl had plenty of time to temper her dreams with reality, as we all must eventually do. Sara smiled hugely as she listened, and after I'd talked about London I couldn't resist beginning to describe Paris.

“You've been to

Paris

?” she exclaimed. “However did you get there?” I explained that my husband Nicholas was a craftsman and trader, and that his work had brought us all over the world. When Elizabeth finally came home around midnight, reporting that her friend had given birth to a healthy baby boy, Sara and I were still at the table, and I was describing the unique scent of tabouli that permeated the streets of Constantinople.

Paris

?” she exclaimed. “However did you get there?” I explained that my husband Nicholas was a craftsman and trader, and that his work had brought us all over the world. When Elizabeth finally came home around midnight, reporting that her friend had given birth to a healthy baby boy, Sara and I were still at the table, and I was describing the unique scent of tabouli that permeated the streets of Constantinople.

“Cousin Layla, I'm glad you and Sara have had such fine conversation, but eight-year-olds need their sleep!” Elizabeth said. “Young lady, off to bed with you! We all have to get up early.”

Sara obediently rose and walked over to the short ladder that led to her pallet in the loft. “I'm glad the baby is fine, Mother. Good night. And good night, Auntie Layla.” Now I was

Auntie

rather than the more formal

Aunt.

That thought warmed me as Elizabeth chatted for a bit about her friend and the baby, and when we blew out the candles and went to bed ourselves I almost hoped Sara was still awake in the loft pallet we shared so I could tell her more about the places she wanted to go, but the child was fast asleep. And soon, so was I.

Auntie

rather than the more formal

Aunt.

That thought warmed me as Elizabeth chatted for a bit about her friend and the baby, and when we blew out the candles and went to bed ourselves I almost hoped Sara was still awake in the loft pallet we shared so I could tell her more about the places she wanted to go, but the child was fast asleep. And soon, so was I.

For a few more weeks, life remained simple and mostly good. All day from Monday through Friday, and then half-days on Saturdays, I worked in the Sabine house, doing all sorts of chores. Saturday afternoons were spent with Elizabeth and Sara shopping in town or enjoying walks through the green hills around Canterbury. On Sunday mornings there was churchâI was pleased Elizabeth attended one where the minister did not adhere to the stern tenets of the Puritansâand then, afterward, perhaps a picnic.

After so many centuries of magical gift-giving, it was in some ways pleasing to live what would be considered a “normal” life. I was often reminded, though, that I was still a fugitive. Reports of the war reached us regularly, often in my letters from Arthur and Elizabeth's from Pamela, which they sent whenever they knew someone who was going between London and Canterbury. In those letters, we learned the king was winning most of the battles against the Roundheads, but he was never quite able to end the war by marching all the way into London.

“Even without Cromwell, who is still supposedly training his troops, the rebels fight just well enough to keep the king from complete triumph,” Arthur wrote. “The Puritans still go around saying God will not let them lose. They're trying to convince the working people that few, if any, real Englishmen are fighting for Charles at all. Their new rude nickname for the king's troops is

Cavaliers,

which, I think, is based on the French

chevalier

or âcavalry.' If the rebels don't win a major battle soon, I don't think they can hold out much longer.”

Cavaliers,

which, I think, is based on the French

chevalier

or âcavalry.' If the rebels don't win a major battle soon, I don't think they can hold out much longer.”

But besides the English rebels, Charles had other troubles. The Scots kept raiding up along the northern border, and there was outright rebellion in Ireland, where most people were Catholics who wanted English Protestantism completely gone from their country. It was rumored that the Roundheads were holding talks with the Scots, Arthur said, hoping to form an alliance with them against Charlesâwho, other rumors had it, was trying to get the Irish Catholics to join him!

It was all very confusing, and ordinary people had trouble keeping track of who was doing exactly what. So long as Avery Sabine was in charge, Canterbury would officially belong to the Roundheads, but as fall 1642 turned into winter, it seemed quite likely Charles was going to beat the rebels of Parliament. In Canterbury's markets and streets, working people began to grumble about Sabine, and how the king might just wreak some awful vengeance on the town in retaliation for its mayor supporting his enemies.

Almost everyone, I think, began looking forward to Christmas that year as an especially welcome time to forget the war. I personally found it quite odd, when October gave way to November, not to be part of annual holiday preparations at either the London or the Nuremberg toy factory. There, I knew, Arthur and Leonardo and Attila and Dorothea and St. Francis and Willie Skokan would be overseeing toy production and planning who would deliver what and where, while, over in America, Nicholas and Felix were doing much the same. I hadn't heard directly from my husband while I was in Canterbury. Arthur mentioned he'd had one letter from Felix saying everything there was fine, and that he'd replied all was generally well in England, though I was away from London for a while.

I missed Nicholas terribly, and planned to join him in America just as soon as the war in England was over, which promised to be soon. The king would win, the Puritans would be commanded to give up trying to force their beliefs on everyone else, and Christmas would once again be safe. At that time, I would no longer be a fugitive, and it would be possible for me to move on and resume my life as an ageless gift-giver. I longed for that moment and, yet, I knew I would be sorry to leave Elizabeth, who I'd grown to love as a sister, and Sara, who I certainly loved like a daughter. She talked to me all the time now, about her dreams and also her disappointments, such as often being reminded in little ways that although she could be friends with Sophia, she could never be considered her equal.

“I'm actually better than Sophia at spelling and sums, but the teacher only praises her and not me, Auntie Layla,” Sara said. “Sophia talks all the time about

her

education and the important man

she

will marry and how I'll be

her

lady-in-waiting. It doesn't matter how smart I am; I'll always be the servant, and, if I marry at all, it will probably have to be to some farmer in Canterbury. I don't think it's fair.”

her

education and the important man

she

will marry and how I'll be

her

lady-in-waiting. It doesn't matter how smart I am; I'll always be the servant, and, if I marry at all, it will probably have to be to some farmer in Canterbury. I don't think it's fair.”

“Much in life isn't fair, Sara,” I replied. “It's for us to find and take advantage of its possibilities, though, instead of being controlled by gloomy thoughts. I had a dear aunt who told me often to keep my dreams and make as many of them come true as I could. That's my advice to you, my love.”

“Your aunt sounds very special,” Sara said. “What was her name?”

“Lodi,” I answered.

“That's a pretty name. Is she still living?”

“In my heart, at least, and now in yours,” I said, and gave Sara a huge hug.

In early December, a package arrived from Arthur along with the usual letter. Anticipating Christmas morning, I had asked that Leonardo personally craft a fine doll for Sara, one with blonde hair and painted blue eyes. He'd outdone himself, fashioning a marvelous wooden toy with real working joints, and I felt some satisfaction that Sophia Sabine, for all her father's wealth, would never own a finer one. There was something in the package that I hadn't expected, too, wrapped carefully in paper. I had never seen the likes of the candy that spilled into my hands.

“Leonardo and Willie Skokan have been collaborating,” Arthur wrote. “These things they call âcandy canes' are the result. Willie says you were the one who suggested them.”

The peppermint sweets had been stretched into sticks about four inches long, and then one end had been curved around in the shape of an upside-down

u,

mimicking exactly the sort of canes older people used to walk, and also resulting in a shape that could, as Willie hoped, dangle as a decoration from the branches of Christmas trees in those countries like Germany that had developed this new holiday tradition. Leonardo's striking red stripes remained on the canes, and they were lovely in their color and simplicity. Since neither Elizabeth or Sara was aroundâI wanted to keep the confectionary as a surprise holiday treatâI sampled a cane, and the sharp peppermint taste was astonishing.

u,

mimicking exactly the sort of canes older people used to walk, and also resulting in a shape that could, as Willie hoped, dangle as a decoration from the branches of Christmas trees in those countries like Germany that had developed this new holiday tradition. Leonardo's striking red stripes remained on the canes, and they were lovely in their color and simplicity. Since neither Elizabeth or Sara was aroundâI wanted to keep the confectionary as a surprise holiday treatâI sampled a cane, and the sharp peppermint taste was astonishing.

I knew it would be all right for Sara to wake up on Christmas day to discover Father Christmas had left her a doll and some candy, because Elizabeth had assured me he was a welcome visitor in their home.

“Of course, Father Christmas can't be everywhere, so my husband, Alan, and I are careful to help him with Sara's presents,” she said. “It's been a hard year with Alan away at sea, but still there will be a new dress for her on Christmas morning.” When I told her I would like to give a doll, she hugged me in thanks for adding to her child's holiday joy.

“It's really a gift straight from Father Christmas and his companions,” I said truthfully, and Elizabeth stared at me in surprise.

“Father Christmas has companions?” she asked.

“Of course,” I replied, smiling.

In my months at Canterbury, I had been accepted into the community, with my plain looks and unremarkable job. Though I'd been careful to make no close friends other than Elizabeth and SaraâI didn't want questions about where I'd come from, because in Avery Sabine's town I assumed there would be Puritan informersâI did have passing acquaintance with a number of people, including the other women who worked for Margaret Sabine. They began talking, during the second week in December, about what the Canterbury mayor might do to discourage the celebration of Christmas.

Other books

Luna the Moon Wolf by Adam Blade

How I Won the Yellow Jumper by Ned Boulting

Iron Sunrise by Charles Stross

Kaleidoscope by Gail Bowen

The Solstice Mistletoe Effect by Serena Yates

Sleepside: The Collected Fantasies by Greg Bear

Justine by Marqués de Sade

The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven: A Remarkable Account of Miracles, Angels, and Life Beyond This World by Kevin Malarkey; Alex Malarkey

Reign of Shadows by Sophie Jordan

Wild Irish (Book 1 of the Weldon Series) by Jennifer Saints