How to Think Like Sherlock (4 page)

Read How to Think Like Sherlock Online

Authors: Daniel Smith

Cut out distractions

If you want to really listen to someone, try to engage in conversation in a place where there isn’t a television showing the football over their shoulder, or where the latest object of your affections isn’t visible. Keeping eye contact with the speaker is a good way of maintaining your listening.

Repeat it

Strange as it sounds, repeating something of particular interest that has been said can help lodge it in your mind. You can repeat it quietly to yourself so as not to unnerve the speaker by seeming to mimic what they are saying.

One of the great advantages of becoming a really good listener is that it builds bonds of trust with those you are listening to and will encourage them to listen to you in turn.

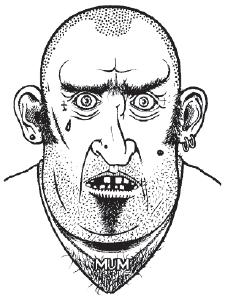

Quiz 5 – Not a Pretty Picture

In this exercise, take a minute to study the artist’s impression of Dangerous Dave, a notorious robber. Reproduce Dave’s face on a separate sheet of paper.

Reading Between the Lines

‘I read nothing except the criminal news and the agony column.’

‘THE ADVENTURE OF THE NOBLE BACHELOR’

It is probably fair to assume that Holmes made the above statement somewhat archly. Able to pluck just the right fact at the most opportune moment, he clearly had a significant breadth of reading. However, his quote about reading only news and gossip columns is suggestive of his ability to fix his focus on the material most useful to the job in hand. But rather than restricting his reading, it is far more likely that Holmes was an accomplished exponent of speed reading, able to digest large amounts of text at a high tempo and extract the information he required.

Studies suggest that an average adult reading speed is somewhere between 175 and 350 words per minute. The trick to speed reading is not merely to see more words in a shorter space of time, but to become more efficient at reading. It is all well and good to scan your eyes over, say, 500 words per minute, but not much use if the meaning of those words does not sink in at such a pace.

Here are a few ideas as to how to become a more efficient reader:

Read in an atmosphere conducive to concentration

Go somewhere quiet. Turn off the television, the radio, your telephone … anything that might distract you.

Learn to chunk!

When we learn to read, we do so in a word-by-word form. However, we are capable of reading blocks of words. Indeed, it has been argued that reading in blocks makes meaning clearer than focussing on each individual word. When an adult reads, their eyes tend to take in more than one word at a time, often scanning ahead of where they think they are in the text. Try it as you read now!

Relax

Typically, your gaze as you read will encompass about four or five words. Now hold this text further away from you and relax your gaze. You may well find you absorb still more words into each block. Your peripheral vision might even take in the end of a line while you are reading in the middle of it. With practise, you should be able to read in chunks of text, significantly cutting down the time required to scan a page.

Learn to focus on key words

Take the following line: ‘This book contains lots of information about the famous detective Sherlock Holmes.’ What are the most important words? Well ‘book’ tells us what we are talking about, while ‘information’ gives us a pretty good idea of the type of contents and ‘Sherlock Holmes’ gives us the specific subject. The other words, while all helpful in their ways, might justifiably be scanned over by a speed reader.

Stop sub-vocalizing

Many of us do something called ‘sub-vocalization’. This means that a little voice in our heads says each word as we read it. A proficient reader really doesn’t need to do this. Your brain understands a word quicker than you can say it. Here is an interesting experiment to show you why we needn’t get caught in the minutiae of words as we read. Consider the following passage of apparent gobbledygook:

I’ts qtuie psolbiese to mkae ssnee of tihs scenetne eevn thguoh olny the fsrit and lsat ltreets of ecah wrod are werhe tehy slhuod be.

Some people are able to discern its meaning almost instantly, while to others it will seem like nothing more than gibberish. So how do some people manage to understand it? Many of us do not read every letter of a word as we scan text. In fact, often we only need the first and last letters of a word. Our brains then do their magic and, by feeding off a mixture of accumulated experience and immediate context, are able to predict what each word is likely to be. (For the record, the passage reads: ‘It’s quite possible to make sense of this sentence even though only the first and last letters of each word are where they should be.’) Sub-vocalization is a bad habit and, like most bad habits, with a bit of willpower, you should be able to stop it.

Stop regressing

Another bad habit is ‘regression’. No, not going back into your subconscious and discovering you were Cleopatra’s favourite eunuch in a past life. When reading, regression is going back over text to check you read it right. Rather than consolidating understanding, this tends to break the flow of concentration and decreases your overall comprehension. Only go back if you really need to.

Use headings

Consider whether your text has any tools to help you speed up your reading. Are there lots of headings summarising contents, or bullet points for you to scan?

Use a finger

Don’t feel you’re too grown up to use a finger to trace your reading. It will help keep your eye focussed on precisely where you are in the text, increasing your pace.

Choose carefully

Accept that some documentation does not lend itself to speed reading. If you’re signing off on a mortgage, for instance, don’t be tempted to take a shortcut on the small print. Similarly, a piece of delicately crafted verse by your one true love should not be read like a set of revision notes.

Armed with this information, have a go at the following exercise.

Quiz 6 – Speed Reading

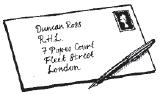

In this extract from ‘The Red-Headed League’, Jabez Wilson, a pawnbroker by trade, is reporting to Holmes a conversation he had with one Duncan Ross, who proposes to employ Wilson in a rather extraordinary position. The passage is 250 words long. Give yourself just thirty seconds to read it, then turn over the page and answer a series of questions to see how much you absorbed.

‘What would be the hours?’ I asked.

‘Ten to two.’

Now a pawnbroker’s business is mostly done of an evening, Mr. Holmes, especially Thursday and Friday evening, which is just before payday; so it would suit me very well to earn a little in the mornings. Besides, I knew that my assistant was a good man, and that he would see to anything that turned up.