How to Think Like Sherlock (2 page)

Read How to Think Like Sherlock Online

Authors: Daniel Smith

Understanding Sherlock

‘I play the game for the game’s own sake.’

‘THE ADVENTURE OF THE BRUCE-PARTINGTON PLANS’

Dear old Sherlock has rather acquired a reputation over the years as an anti-social, unfeeling machine with a fearsome streak of arrogance. Such a description is not entirely unjustified. Even faithful Watson – in one of his more exasperated moments – described him as ‘a brain without a heart, as deficient in human sympathy as he was pre-eminent in intelligence’. Then, in a more considered moment, Watson called him ‘the best and wisest man whom I had ever known’.

In truth, Holmes nestled somewhere uncomfortably between these two descriptions. The ordinary, everyday world largely bored him, which could make him seem distant, disinterested and even callous. This was an unfortunate side effect of his on-going quest for excitement, for the unusual, for the sort of problem that could only be solved by his particular type of mind.

‘I know, my dear Watson,’ said Holmes in ‘The Red-Headed League’, ‘that you share my love of all that is bizarre and outside the conventions and humdrum routine of everyday life.’ It was this desire to rise above the mundane that so often drove him, sometimes onwards and upwards, sometimes into extreme danger and sometimes toward the terrible black dogs of his depression.

What cannot be in doubt is that the Great Detective took on all his work wholeheartedly, risking his own wellbeing in pursuit of his chief goal: defeating the worst criminal minds in the land. It was work that imperilled his life but which fulfilled a deep-seated need within him for intellectual challenge and heart-stopping adrenalin rushes. Take this short extract from ‘The Boscombe Valley Mystery’, which exquisitely captures Holmes as the thrill of the chase takes him over:

Sherlock Holmes was transformed when he was hot upon such a scent as this. Men who had only known the quiet thinker and logician of Baker Street would have failed to recognise him. His face flushed and darkened. His brows were drawn into two hard black lines, while his eyes shone out from beneath them with a steely glitter. His face was bent downward, his shoulders bowed, his lips compressed, and the veins stood out like whipcord in his long, sinewy neck. His nostrils seemed to dilate with a purely animal lust for the chase, and his mind was so absolutely concentrated upon the matter before him that a question or remark fell unheeded upon his ears, or, at the most, only provoked a quick, impatient snarl in reply.

There were many counterpoints to these moments of exhilaration. In the absence of suitable cases to invigorate his soul, Holmes displayed classic signs of depression and resorted to such unsavoury outlets for his energies as cocaine abuse. ‘I get in the dumps at times,’ he told Watson in

A Study in Scarlet

, ‘and don’t open my mouth for days on end. You must not think I am sulky when I do that. Just let me alone, and I’ll soon be right.’

Equally destructive was his inability to consider his own basic physiological requirements when faced with an unresolved conundrum. In these circumstances, Watson memorably recorded how he ‘would go for days, and even for a week, without rest, turning it over, rearranging his facts, looking at it from every point of view until he had either fathomed it or convinced himself that his data were insufficient’. Had he been a fan of those signs one sometimes finds in a certain kind of office environment, he might well have had one on his desk at 221B Baker Street that read: ‘You don’t have to be mad to work here. But it helps!’

All of which is to say, being Holmes was no easy option, and to follow in his intellectual footsteps is not a journey for the faint-hearted. Holmes went about his work because he had no other choice – it was what made him who he was. Without it, there was little to define him. He alluded to his enormous sense of duty in

A Study in Scarlet

: ‘There’s the scarlet thread of murder running through the colourless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it, and isolate it, and expose every inch of it.’ Meanwhile, Watson would say of him that ‘like all great artists’ he ‘lived for his art’s sake’.

Do You Have the Personality?

‘The strong, masterful personality of Holmes dominated the tragic scene …’

‘THE ADVENTURE OF THE SOLITARY SCIENTIST’

We all make sweeping judgements about people. Him over there is arrogant, her in the corner is needy, and as for her friend … well, where do I start?

The truth is that many of the judgements we make about personality are instinctive and say as much about us as they do about the person we are judging. The study of personality can never amount to an exact science. However, there is a body of long-established research into personality that gives us a good basis for discussion. So how does your personality type match up against that of Holmes?

The founding father of the psychological classification of personality types is Carl Jung, who published his landmark study

Psychological Types

in 1921. He outlined two pairs of cognitive functions. On the one hand, the ‘perceiving’ (or ‘irrational’) functions of sensation and intuition, while on the other hand, the ‘judging’ (or ‘rational’) functions of thinking and feeling. In layman’s terms, sensation is perception as derived from the senses; thinking is the process of intellectual and logical cognition. Intuition is perception as derived from the subconscious while feeling is the result of subjective and empathetic estimation.

As if all this weren’t quite complicated enough, Jung threw in another element: an individual’s personality may be classified as extrovert (literally ‘outward-turning’) or introvert (‘inward-looking’). In Jung’s analysis, each individual has elements of all four functions to a greater or lesser degree, with each manifesting in an introverted or extroverted way.

Jung’s philosophy was subsequently developed by many different parties over the years. Among them were the mother-and-daughter team of Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers, who developed the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), a trademarked assessment first published in 1962 that categorises personality into one of sixteen types based on four dichotomies:

Extraversion (E) – Introversion (I)

Sensing (S) – Intuition (N)

Thinking (T) – Feeling (F)

Judging (J) – Perception (P)

Personality types are represented by a four-letter code comprising the relevant abbreviations noted above. Of course, Sherlock Holmes never underwent such a personality test because he pre-dates them, is fictional, and would have had no truck with psychobabble. However, others have retrospectively attempted to assess him, with a broad consensus that he would probably lie somewhere between an INTP and ISTP classification: introverted, favouring intellectual reasoning over reliance on his feelings, and generally acting in response to information gathered rather than pre-judging a situation. The question of whether he best fits the sensing or intuition classification is much less clear. Incidentally, it has been suggested that Watson’s profile best fits an ISFJ classification.

But what about you? Are you more of a Holmes or a Watson? Surely not a Moriarty? The MBTI test can be undertaken under the supervision of registered practitioners but there are many other Jungian-based tests that are free on the internet and can be self-administered. However, it is worth noting that personality testing should not be treated as a game nor as an exact science. Answering half a dozen questions on the internet cannot define your personality, for better or worse! But using a reputable personality test might offer you some useful insights into how you operate.

Developing an Agile Mind

‘I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix.’

‘THE ADVENTURE OF THE MAZARIN STONE’

While Holmes’s personality and motivations are endlessly interesting enigmas, were it not for his remarkable intellectual capacity, you would not be here reading about him. There are plenty of interesting characters in life and literature, but very few able to solve an apparently unsolvable riddle like the Great Detective.

Alas, few of us can ever hope to match Holmes in the bulging brains department. That need not be a source of shame, though, for has there ever been a more penetrating intellect in literature than Holmes? ‘You have brought detection as near an exact science as it ever will be brought in this world,’ Watson told him in

A Study in Scarlet

(a piece of flattery that had even Holmes ‘flushed up with pleasure’). ‘Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner,’ Holmes himself would declare in

The Sign of Four

.

However, do not be fooled into thinking that Holmes is only concerned with cold analysis and the weighing up of empirical evidence. Holmes talked about his work as much in terms of art as science. It was a sentiment he returned to in ‘The Problem of Thor Bridge’, when he spoke of ‘that mixture of imagination and reality which is the basis of my art.’ In

The Valley of Fear

, he reiterated the necessity for creative thinking: ‘How often is imagination the mother of truth?’

The great news is that if you don’t feel like you are using your grey matter to Holmesian levels, you can train it to work better for you. This is not some self-help claptrap but scientifically proven fact. The brain is incredibly durable and can grow and change to cope with any number of new demands made upon it. You just have to make sure you get it into shape to meet new challenges.

Do you want proof? How about London’s registered taxi cab drivers. To join the profession, applicants must undertake years of study known as ‘the Knowledge’, learning some 320 key routes encompassing thousands of streets within a six mile radius of Charing Cross in central London. Research students of ‘the Knowledge’ have typically shown an increase in the volume of the hippocampus (a part of the brain integral to memory).

The most famous winner of the television quiz was the 1980 champion Fred Housego, a cabbie who kept up his licence even after becoming a media celebrity. No wonder Holmes was accustomed to seeking out hansom cab drivers as fonts of information in so many of his cases!

Warming-Up

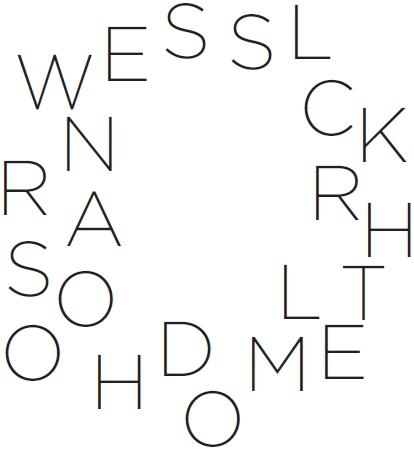

Regularly exercising your brain by playing mental games and doing quizzes has been shown to offer a defence against dementia in older people. But you are never too young to get into the habit. Here is a mixture of word and number games.

Quiz 1 – Letter Scramble

There are two words to find in the first puzzle and two in the second.