How to Think Like Sherlock (6 page)

Read How to Think Like Sherlock Online

Authors: Daniel Smith

7 Bonneparte, Boney, The Little Corporal, Corsican Ogre, Husband of Josephine, Emperor of the French

8

9

10 Cu + Copacabana/Bondi/Venice

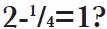

Quiz 9 – What Next?

In this quiz, attempt to complete each sequence by filling in the last two missing elements. There is a clear pattern behind each sequence but you will have to rack your brains to work out just what it is.

1.

Genesis Exodus Leviticus Numbers Deuteronomy Joshua Judges Ruth __________ __________

2.

M T W T F __ __

3.

31 28 31 30 31 30 31 31 30 31 __ __

4.

M V E M J S __ __

5.

A S D F G H J __ __

6.

Moscow, Los Angeles, Seoul, Barcelona, Atlanta, Sydney, Athens, Beijing, __________, __________

7.

1660 1685 1688 1702 1714 1727 1760 1820 1830 1837 1901 1910 _____ _____

8.

Czech Republic, Slovakia, Eritrea, Palau, Timor Leste, Montenegro, __________, __________

(Write your answers on a separate sheet of paper)

Quiz 10 – What on Earth?

Some lateral-thinking teasers to tax you.

1.

A man walks into a bar and asks for a glass of water. The barman goes to pour one when he suddenly lurches at the customer across the bar, letting rip a blood-curdling roar. The customer thanks the barman and leaves. Why?

2.

Louise’s father has three daughters. The oldest is called April and the next oldest is called May. What is the youngest called?

3.

Tom goes into Harry’s shop and asks Harry how much a chocolate bar costs. Harry says it’s sixty pence for one or a pound for two. Tom puts a pound down on the counter and Harry asks if he wants one or two bars. A few minutes later, Dick enters the shop and asks Harry the same question about price, receiving the same answer. Dick also puts a pound down on the counter and Harry gives him two bars without asking how many he wants. Why?

4.

Is it legal for a woman to marry her widower’s brother?

5.

A French plane crashes in Luxembourg. Where should the survivors be buried?

6.

A grove has three crates labelled ‘Oranges’, ‘Lemons’ and ‘Oranges & Lemons’. Each of the boxes is incorrectly labelled. How can you work out which label goes on which box by removing one piece of fruit from one box only?

7.

Dodgy Don is suspected of theft from a company he has just been visiting. He is stopped by the police but they find nothing incriminating either on him or in the van he is driving. Nonetheless, the police arrest him and charge him with theft. What had he stolen?

Choosing Your Friends Wisely

‘I confess, my dear fellow, that I am very much in your debt.’

‘THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES’

For all that Holmes stands alone as the greatest detective in English literature, he was but one half of a remarkable double act even though he was sometimes reluctant to admit it. Holmes was self-confident (even arrogant) and occasionally teased Watson mercilessly. Even when he was ‘being nice’, his compliments could be distinctly double-edged. In

The Hound of the Baskervilles

, he told Watson rather condescendingly: ‘It may be that you are not yourself luminous, but you are a conductor of light. Some people without possessing genius have a remarkable power of stimulating it.’

Some portrayals in television and film productions (notably Nigel Bruce’s Watson alongside Basil Rathbone’s Holmes in the Hollywood movies of the 1930s and 1940s), depicted Watson as a bungler. He was not. Here was a qualified doctor who had served his country in India and Afghanistan. He had foibles of his own (there are numerous suggestions of a historic overfondness for alcohol and gambling), but in his partnership with Holmes he was never less than loyal and extraordinarily brave, and often provided that dose of humanity lacking in the Great Detective.

Holmes knew this too. When he baited Watson, it was usually done with the mischievous affection common to strong male friendships. Holmes had the insight to recognise that Watson filled some of the gaps in his own personality and was the perfect ally whenever he was needed. Watson was Holmes’s ‘someone … on whom I can thoroughly rely’. During their Baskerville adventure, Sherlock admitted that ‘There is no man who is better worth having at your side when you are in a tight place’.

Crucially, Watson was also an impeccable foil for Holmes, someone with whom the Great Detective could discuss his train of thought (though he often did so in an infuriatingly enigmatic manner). Holmes even stated: ‘Nothing clears up a case so much as stating it to another person.’ If there were gaps in his thinking, talking over his deductions with Watson was a sure way to expose them.

Watson in his turn understood what he brought to the crime-fighting party. ‘I was a whetstone for his mind,’ he wrote in ‘The Adventure of the Creeping Man’. ‘I stimulated him.’ In ‘His Last Bow’, a troubled Holmes told his old friend: ‘Good old Watson! You are the one fixed point in a changing age.’ But perhaps Holmes summed it up best in ‘The Adventure of the Dying Detective’: ‘You won’t fail me. You never did fail me.’

Holmes, a man who by his own admission had ‘never loved’, knew that, in the words of John Donne, ‘no man is an island’. He understood that a trusted friendship did not lessen him or steal glory away from him but made him more than he otherwise would have been. He would, no doubt, have agreed with the seventeenth-century English poet Abraham Cowley:

Acquaintance I would have, but when it depends

Not on the number, but the choice of friends.

Accepting Good Fortune

‘We have certainly been favoured with extraordinary good luck.’

‘THE ADVENTURE OF THE BERYL CORONET’

It is easy to assume that Sherlock’s great mind guaranteed success in his cases but he was subject to luck – good and bad – just like the rest of us. In ‘The Adventure of Black Peter’, the case was solved ‘simply by having the good fortune to get the right clue from the beginning.’ Alternatively, in

The Hound of the Baskervilles

, Watson talked of how ‘Luck had been against us again and again in this enquiry, but now at last it came to my aid.’

None of us can control the influence of good fortune on our lives but it may just be possible to tip the odds in our favour. In 2003, Professor Richard Wiseman revealed the results of his ten-year study into good and bad luck. His findings suggested that ‘lucky’ people generate their own good luck. He wrote in the

Daily Telegraph

:

My research revealed that lucky people generate good fortune via four basic principles. They are skilled at creating and noticing chance opportunities, make lucky decisions by listening to their intuition, create self-fulfilling prophesies via positive expectations, and adopt a resilient attitude that transforms bad luck into good.

Wiseman is not the first authority to suggest that we can influence our own fortune. Ovid wrote, ‘Luck, affects everything; let your hook always be cast; in the stream where you least expect it, there will be a fish.’ The great movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn noted ‘The harder I work, the luckier I get.’

There is anecdotal evidence, too, that great things can spring from a slice of good luck. Everything from Christopher Columbus stumbling upon America while searching for a new eastern passage, to Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin and even the invention of Coca-Cola, all owed a great deal to good fortune.

In short, if good fortune chooses to search you out, do not reject it. Embrace it. Sherlock Holmes certainly did when it came around.

Learning From Your Mistakes

‘I made a blunder, my dear Watson – which is, I am afraid, a more common occurrence than anyone would think who only knew me through your memoirs.’

‘SILVER BLAZE’

Everybody makes mistakes. Even the Great Detective. But he knew that to make a mistake is forgivable so long as you make it only once. Consider his comments on the subject in ‘The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax’:

‘Should you care to add the case to your annals, my dear Watson,’ said Holmes that evening, ‘it can only be as an example of that temporary eclipse to which even the best-balanced mind may be exposed. Such slips are common to all mortals, and the greatest is he who can recognise and repair them. To this modified credit I may, perhaps, make some claim.’

Today, making a mistake is considered an integral factor in progressing and developing. In 2007, Robert Sutton, a professor of management science and engineering at Stanford University, wrote a blog for the Harvard Business Review: