i bc27f85be50b71b1 (281 page)

Read i bc27f85be50b71b1 Online

Authors: Unknown

In patients with upper-extremity amputation, a sling may

be used to help manage edema.

Phantom limb

Often described as a cramping, squeezing, shoming, or

pain

burning pain felt in the part of the extremity that has

been removed. The physical therapist may use

desensitizing techniques (e.g., massaging the residual

limb), exercise, hot and cold therapy, electrical

stimulation, or other modalities when phantom limb

pain is determined as the cause of the patient's pain.

Hypersensitivity

Patient should be encouraged to rub the residual limb with

increasing pressure as tolera[ed.

Skin condition

Ensure stability of new incision(s) before, during, and

after physical therapy intervention. Examine the incision for any changes in [he appearance (size, shape,

open areas, color), temperature, and moisture level.

Instruct patient and nursing staff on importance of frequent position changes to prevent skin breakdown.

Implement out-of-bed activities as soon as possible.

Instruct patient in active movements and bed mobility

activities such as bridging, rolling, and moving up and

down in the bed.

Sources: 03ra from B Engslrom, C Van de Ven (eds). Thcrapy for Ampurees (3rd cd).

Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingsrone, 1999j27-37, 43-45; B May (cd). Amputations

and Prosrhcrics: A Case Study Approach. Phibdelphia: FA Davis, 1996;73,86-88; and

SN Banerjee (cd). Rehabilirarion Management of Ampurees. Balrimore: Williams &

W;lk;ns, 1982;30-33, 255-258.

APPENDIX VII: AMPlffATION

895

Table VII-4. Specific Considerations and Treatment Suggestions for

Patients with Upper- or Lower-Extremiry Amputation

Consideration

Treatment Suggestions

Joint

Upper extremiry

conrracture

Physical therapy should consist of active movements of all

of the joints above the level of the amputation,

including movementS of the scapula. Patients who use

upper-extremity slings to fixate the arm in elbow

flexion and shoulder internal rotation should be

examined regularly for contractu res.

Lower extremity

The physical therapist should provide the patient and

members of the nursing scaff with education on residual

limb positioning, proper pillow placement, and the use

of splint boards.

Patients with a below-the-knee amputation will be mOst

susceptible to knee flexion contraction. A pillow should

be placed under the tibia rather than under the knee to

promote extension.

Patients with above-the-knee amputations or disarticulations will be most susceptible to hip flexor and

abductor contractures.

The physical therapist should begin active range-of-motion

exercises and provide passive stretching as indicated.

Decreased

Upper extremiry

functional

During ambulation, patients tend to flex their tfunk

mobility

roward the side of the amputation and maintain a stiff

gait panern that lacks normal arm swing. Patients often

need gait, balance, posture retraining, or a combination

of these.

It is important to work on active movements, specifically

the movements that might be used for powering a prosthesis, such as in [he following:

Transradial body powered prosthesis: elbow extension,

shoulder flexion, shoulder girdJe protraction. or a

combination of these

Transhumeral body powered prosthesis: elbow flexion,

shoulder extension, internal rotation, abduction and

shoulder girdle protraction and depression.

896 AClITE CARE HANDBOOK FOR PHYSICAL THERAPISTS

Table VU 4. Continued

-

Consideration

Treannenr Suggestions

Lower extremity

Techniques should range from bed mobiliry training to

transfer training to ambulation or wheelchair mobility.

Patients with bilateral above-knee amputacions will

need a custom wheelchair that places the rear axle in a

more posterior position to compensate for the

alteration in the patient's center of gravity when sitting.

Sources: Data from LA Karacoloff, FJ Schneider (cds). Lower Extrcmity Ampmation: A

guide to Functional Outcomes in Physical Therapy Managcmcnt. Rockville, MD:

Aspen, 1985; B Engstrom, C Van de Ven (cds). Therapy for Amputees (3rd cd). Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone, J999;27-37, 43-45, 243-257; B May (ed). Amputations and Prosthetics: A Case Srudy Approach. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996;86-88; SN Banerjee (cd). Rehabiliration Managemcll( of Amputees. Baltimore: Williams &

Wilkins, 1982;30-33,255-258; and R Ham, L Cofton (cds). Limb Ampuration: From

Aetiology to Rehabilitation. London: Chapman & Hall, 1991;136-143.

References

I. Engsrrom B, Van de Ven C (cds). Therapy for Ampurees (3rd cd). Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingsrone, 1999;27-37, 43-45, 149-150, 187-188, 208.

2. Karacoloff LA, Schneider FJ (eds). Lower Exrremiry Amputation: A

Guide to Functional Outcomes in Physical Therapy Management. Rockville, MD: Aspen, 1985.

3. Thompson A, Skinner A, Piercy J (eds). Tidy's Physiotherapy (12th ed).

Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1992;260.

VIII

Postural Drainage

Michele P. West

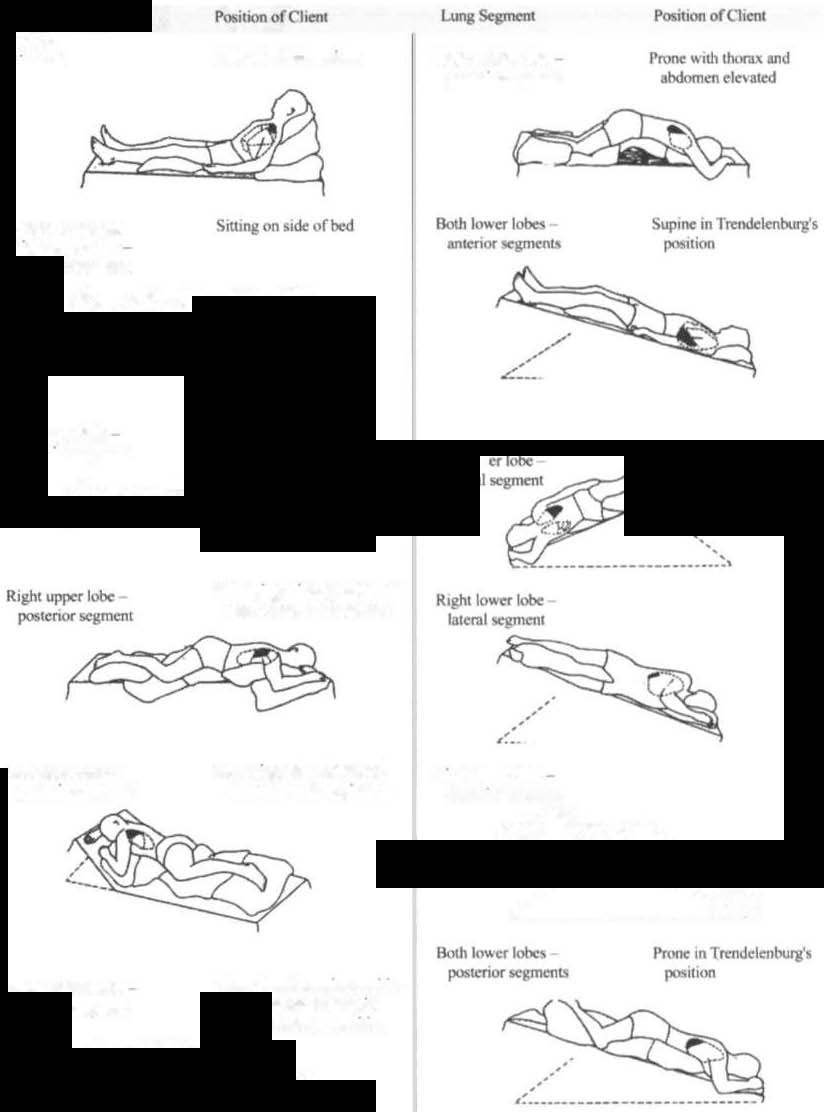

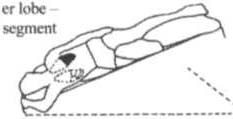

Postural drainage is the positioning of a patient with an involved lung

segment as close to perpendicular to the Aoot as possible to facilitate

the drainage of bronchopulmonary secretions.' Figure Vlll-] demonstrares the various postural drainage positions most applicable in the acute care setting. The lise of postural drainage as an adjunct to other

techniques (mainly breathing and coughing exercises, vibration, shaking, and percussion) can be highly effective for mobilizing retained secretions and maximizing gas exchange. The physical therapist

should note that there are many clinical contraindicarions and considerations for postural drainage that may require position modification to maximize patient safety, comfort, and tolerance.

The contraindications for the use of Trendelenburg (placing the

head of the bed in a downward position) include the following2•3:

•

Patients in which an increase in intracranial pressure should be

avoided

•

Uncontrolled hypertension

• Uncontrolled or unprotected airway with a risk of aspiration

•

Recent gross hemoptysis

897