i bc27f85be50b71b1 (54 page)

Read i bc27f85be50b71b1 Online

Authors: Unknown

MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM 175

A

B

c

o

E

F

Figure 3-3. Examples of ullstable pelvic fractures include (A. 8. and C) vertical shear (Malgaigne) fractures involving ischiopubic rami and disruption of all ipsilateral sacroiliac joint, he they fA) throughout the ioint itself, (B)

through a (racture of the sacral wing, or (e) through a (racture on the iliac

bone. D. Straddle (rac/ures, involving all four ischiopubic rami, E. Buckethandle fractures, involving all ischiopubic ramus and contralateral sacroiliac joint. F. Dislocations invo{/Jing one or hoth sacroiliac joints and the symphysis pubis. (With permission from LN McKinnis /ed). Fundamentals of Orthopedic Radiology. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1997:225.) fractures only and can decrease post-traumatic hemorrhage. It is a good

choice if abdominal injuries are present. External fixation will not stabilize vertical displacement." ORIF techniques are the optimal choice of treatmem for anterior and posterior pelvic displacement. Risks are

high and should be taken only when benefits of anatomic reduction and

rigid fixation ourweigh problems of hemorrhage and infection."

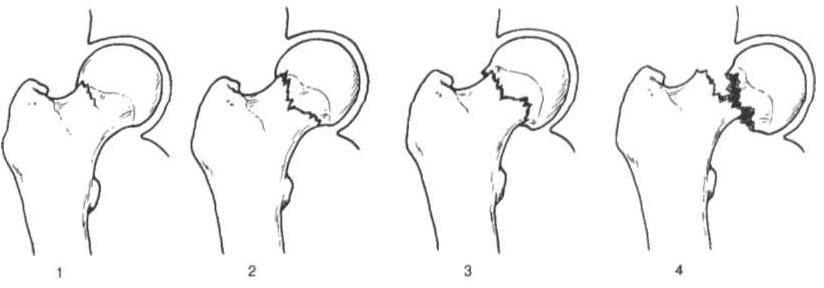

Acetabular Fracture

Acetabular fracture occurs when a high-impaCt blunt force is transmitted at one of four main points: the greater trochanter, a flexed knee, the foot (with the knee extended), or the posterior pelvis." The

exact location and severity of the fracture (Figure 3-4), with or without dislocation, can depend on the degree of hip flexion and extension, abduction and adduction, or internal and external rotation at the time of injury." Acetabular fractures are highly associated with

multiple injuries and shock. Common immediate and early complications associated with acetabular fracture include retroperitoneal

176

AClJTE CARE HANDBOOK FOR PHYSICAL TIIERAPIST!t

A

B

c

o

Figure 3-4. Classificatioll of acetabular fractures. A. Anterior column.

B. Posterior column. C. Transversel involving both columns. D. Complex or

T shaped, involving both columns. (With permission from LN M,K",nis led/.

Fundamentals of Orthopedic Radiology. New York: Oxford Umverstty Press,

1997;227.)

hematoma, gastrointestinal or urologic injury, degloving injury, deep

venous thrombosis (OVT), pulmonary embolism, infection, and sciatic and superior gluteal nerve injury.13 Common late complications include AVN of the femoral head or acetabular segment, hypertrophic

ossification, and post-traumatic arthritis." Chapter Appendix Table

3-A.2 describes the classification and management of acetabular fractures. Acetabular fractures are by nature intra-articular; hence, the management revolves around the restoration of a functional weightbearing joint while avoiding osteoarthritis.13 An acetabular fracture is a complex injury. Determinants of outcome include fracture partern,

degree of injury to the vascular Status of the femoral head, the presence of neurologic injury, and the accuracy of reduction of the roof of the acetabulum."

Hip Dislocatioll

Hip dislocation is the result of a high-velocity impact force and can

occur in isolation or with a femoral or acerabular fracture. The

majority of hip dislocations occur in a posterior direction, and anterior dislocations are rare.16 A patient with a posteriorly dislocated hip has a limb that is shortened, internally rotated, and adducted in

slight flexion.'7 An anteriorly dislocated hip appears adducted and

externally rotated.16

Management of hip dislocation without fracture includes closed

reduction under consciolls sedation and muscle relaxation followed

MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

177

by traction or open reduction if closed reduction fails. Functional

mobility (typically partial weight-bearing or weight-bearing as tolerated), exercise, and positioning are per physician order based on hip joint stability and associated neurovascular injury. Hip dislocation

with fracture typically warrants surgical repair.

Clillical Tip

• Posterior hip dislocation precautions typically exist

after hip dislocation reduction. This limits hip flexion to

80-90 degrees, internal rotation to 0 degrees, and adduction to 0 degrees.

• Indirect restriction of hip movement after posterior dislocation during rest or functional activity can be achieved with the use of a knee immobilizer or hip abduction brace.

This may be beneficial if the patient is confused or noncompliant.

Femoral Head and Neck Fractures

Femoral head and neck fractures are often referred to as hip fractures.

They can be classified as intracapsular or extracapsular. Femoral head

and neck fractures occur from a direct blow to the greater trochanter,

from a force with the hip externally rotated, or from a force along the

femoral shaft. IS In the elderly, a femoral neck fracture can occur with

surprisingly little force owing to osteoporosis of the proximal femur.

Femoral neck fractures in younger adults are almost always rhe result

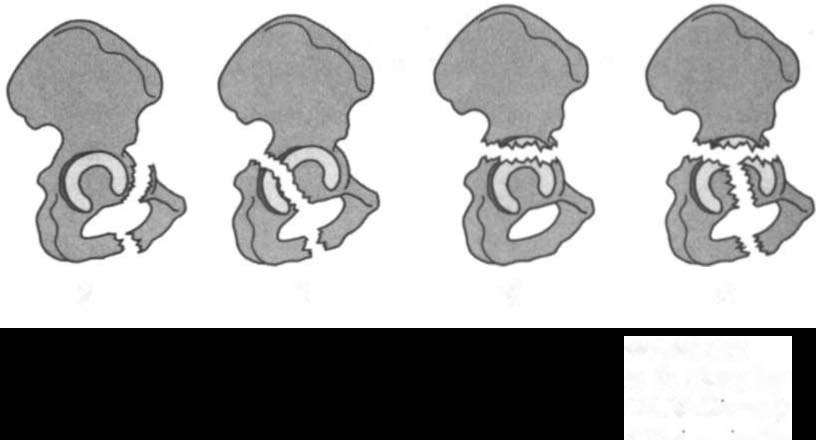

of high-impact forces, such as mOtor vehicle accidents (MVAs). Intracapsular fractures are located within the hip capsule and are also called subcapital fractures. The four-stage Garden Scale (Chapter

Appendix Table 3-A.3) is used to classify femoral neck fractures and

is based on the amount of displacement and the degrees of angulation

(Figure 3-5). Clinically, Garden III and IV fractures are complicated

by a disruption of the blood supply to the femoral head as a result of

extensive capsular trauma . Poor blood supply from the circumflex

femoral artery can lead to AVN of the femoral head, fracture nonunion, or both.1

Extracapsular fractures occur outside of the hip capsule. They can

be further classified as intertrochanteric or subtrochanteric. Intertrochanteric fractures occur between the greater and lesser trochanters.

Subtrochallteric fractures occur in the proximal one-third of the fem-