In the Valley of the Kings (23 page)

Read In the Valley of the Kings Online

Authors: Daniel Meyerson

Tags: #History, #General, #Ancient, #Egypt

“I will leave the reader to decide whether the great cat was the malevolent spirit which … had burst its way through the bandages and woodwork and had fled into the darkness; or whether the torn embalming cloths represented the natural destructive work of Time, and the grey cat was a night wanderer which had strayed into my room and had been frightened by the easily explained bursting apart of the two sides of the ancient Egyptian figure.”

Naturally or supernaturally, the cat was out of the coffin; and with the necropolis feline as tutelary spirit, Carnarvon’s new career was under way. He continued digging with undiminished enthusiasm—though he uncovered nothing of importance (or rather nothing that he considered important). Among his finds, though, there was an old wooden tablet that had cracked in half—but what of it? Carnarvon was looking for some beautiful objet d’art and tossed the tablet into a basket along with the other ancient debris, potsherds, and scraps of mummy bandages.

His carelessness caused three crucial lines to be lost, for the tablet is inscribed. On one side were the sayings of the sage Ptahhotep, while the other contained a record from one of the least documented periods in Egyptian history—the national rebellion against the invading Hyksos, nomadic “shepherd kings” who ruled Egypt for some two and a half centuries (ca.

1800 BC

). It will become known as “the Carnarvon Tablet,” though at the time it was only the Carnarvon washboard, some ancient junk he dropped off at the inspector’s office on his way back to Cairo. As it turned out, though, Carnarvon’s washboard would be his calling card with Carter.

Weigall, as inspector responsible for overseeing the Valley of the Kings, wrote indignantly to the linguist Francis Llewellyn Griffith, “Towards the end of the work [Carnarvon’s dig], I had to go

away, and when I returned to Luxor, Lord Carnarvon had gone, leaving his antiquities in my office. There was a basket full of odds and ends. Amongst these, stuffed anyhow into the mouth of the basket was this tablet, in two pieces, and I am sure this rough handling is responsible for some of the flaking. A sadder instance of the sin of allowing amateurs to dig could not be found. Lord Carnarvon does his best, and sits over his work conscientiously; but that is not enough.”

Griffith replied, “It is grievous to think the plaque may have been perfect when found. I have worked at it again since I wrote to you … the three lines from the middle are a great loss. It is the most important document we have next to the el Kab Ahmosi inscriptions.”

Sir Alan M. Gardiner, the most respected linguistic authority of the day, wrote in the

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology

, “No single inscription has been more important in the last ten years.”

The grieved linguists pored over the now only half-comprehensible boasts of the warrior Kamose (a distant ancestor of Tutankhamun’s), who “at the time of the perfuming of the mouth [early morning] pounced on the foreign enemy like a hawk, destroying his wall, slaying his people, carrying off slaves, cattle, fat and honey—the hearts of my soldiers rejoicing.” Meanwhile, Carnarvon—oblivious to the archaeological suffering he had caused, enthusiastically made boasts of his own. Speculating on the endless possibilities before him, he announced, “I would rather discover a royal tomb than win the Derby!”

The archaeologists appealed to Maspero, who, continually harassed for funds, was not anxious to alienate Carnarvon. On the one hand, a wealthy patron was not easy to come by. On the other, Maspero was a scholar sensitive to his colleagues’ concerns. What was more, he saw the situation as a way of rehabilitating Carter, whose talents he valued and whose situation he deplored. Why

not arrange it so that Carnarvon’s excavations were carried out by Carter—surely a satisfactory arrangement from every point of view, Maspero decided.

Carnarvon agreed immediately—a “learned man” was just what he required since he hadn’t had the time to sufficiently “get up” on the subject. Though he’d heard the gossip about Carter, the man’s stubbornness attracted him rather than otherwise—for he was unconventional himself, down to the rebellious brown shoes he wore to Ascot.

For Carter, who had been languishing in the twilight world of dealers and picturesque watercolors since his resignation as inspector in 1905, this opportunity was nothing less than a resurrection. He went to meet Carnarvon at Luxor’s Winter Palace, where they sat on the hotel’s Nile-side terrace and discussed the upcoming 1909 season. And where they took stock of each other. Though “Dr. Johnny”—Carnarvon’s personal physician, whom he frequently kept by his side—hovered in the background, Carter could see that the nobleman was determined and energetic, if inexperienced. And Carnarvon immediately liked Carter, who obviously lived with only one thought in mind—to make a great find.

The American entrepreneur Theodore Davis had held the excavation concession for the Valley itself since 1902 and showed no sign of relinquishing it. For the time being, they would have to dig around the Valley proper: in the cliffs above Hatshepsut’s temple, at the bottom of the slopes of Dra Abu el-Naga, the Birabi, the Assasif, and at the edge of the cultivation, the lush green land flooded by the Nile. It was not the Valley of the Kings proper, but still there was no telling what they might find here. Carter unrolled his map, while Carnarvon—defying both Dr. Johnny and the odds—raised a glass to their partnership.

And so the match was made, courtesy of Maspero, archaeological cupid, with good results soon following. “After perhaps ten days work we came upon what proved to be an untouched tomb,”

the thrilled Carnarvon wrote of “his first.” “I shall never forget the sight. There was something extraordinarily modern about it. Several coffins were in the tomb, but the first that arrested our attention was a white brilliantly painted coffin with a pall loosely thrown over it, a bouquet of flowers lying just at its foot. There these coffins had remained untouched and forgotten for two thousand five hundred years.”

Over the next seven years, from 1907 until the outbreak of World War I, they made many such discoveries in the Theban hills. Carnarvon in his elegant Edwardian getup hovered nearby, while Carter like a conjuror brought up from the earth mummies, mirrors, game boards, statues, jewelry, musical instruments, and magical oars—along with the so-called beds of Osiris, the resurrected god of the dead torn to bits by his evil brother, Seth, and pieced together by his wife-sister, Isis. The hollow wooden Osiride boxes (shaped in the god’s form) were filled with seeded soil that began to sprout millennia ago under their mummy bandages, a symbol of the irrepressible, enduring nature of life and its triumph—even in the tomb—over death.

There was almost no knowing what or who would appear next as the dour archaeologist presented his patron with the artifacts of a vanished world. Carnarvon watched, awed, deferential; Carter was gruff, focused, sometimes aloof, sometimes taking the time to explain. This was the nature of their relationship from now until the end. A colleague (Arthur Mace) recorded later that when he was working with the two in Tut’s tomb, Carnarvon was always wandering about, pestering Carter with questions, and that Carter “spoke to him as if he were a naughty child!”

By that time, they had lived through more than sixteen years of shared disappointments, victories, and anxieties: Would a fragile antiquity survive as sand was brushed from its surface? Would the overhanging tomb masonry collapse or hold? Which museums should receive one of the sixty-four painted coffins from tomb

#37? How best to pack up the Amunemheb statue—a breathtaking bronze of a naked young boy, his shaven head thrown back, his lithe body striding forward, his expression alert, intent, alive.

But through all the years of Carter’s preliminary work with Carnarvon, he never stopped brooding over “the Valley.” The activities of the American millionaire Theodore Davis, who held the concession to dig there, were widely reported. Carter followed Davis’s excavations step by step as numerous tombs were uncovered, some royal, some not, all plundered in antiquity with one exception: the almost intact tomb of Thuya and Yuya, parents of Queen Tiye. The tomb created a sensation with its fine furniture and perfectly preserved mummies, but it was soda pop next to the champagne of Tut’s tomb—which Davis suddenly announced to the world that he had discovered as well.

Imagine that you are Carter. You are in the middle of the complicated excavation of a reused Middle Kingdom tomb (ca.

2000 BC

) that has evidence of intrusive burials all the way down the line: fine New Kingdom coffins (ca.

1500 BC

) and late dynastic mummies (ca.

900 BC

) and piles of Graeco-Roman “junk” (ca.

330 BC-AD 200

). It requires all your concentration as you work in the mongrel tomb with its intermingled remains. But how can you keep your mind on Tetiky, ancient mayor of Thebes—or even on Tetiky’s unwrapped wife, two mummified miscarriages between her legs, when you hear that that arrogant, careless, filthy rich American had finally gotten the prize you most desired?

Davis was jubilant—he went crowing all over the Valley—now there would be another royal find to his credit! And another one of his lush, expensive, leather-bound publications to announce it. Volumes notoriously and maddeningly short on crucial archaeological detail—Davis had no patience with the vital facts and information compiled by his archaeologists—and equally notoriously and maddeningly long on “modest” bows by the immodest Davis. And in fact

The Tombs of Harmhabi and Toutânkhamanou (The

Tombs of Horemheb and Toutankhamun)

by Theodore Davis was just such a work—glossy, flashy, vain, and, archaeologically speaking, useless.

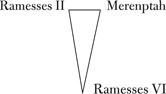

Davis was triumphant—while Carter was left with what, after years of calculation? A hatched map showing the area where Tut’s tomb must be, a triangle formed by three royal tombs that Carter had marked out with a firm, experienced hand:

Which was just where that damned Davis found him.

But then Carter learned the details. The tomb (given the number 58) was one room—a naked little rough chamber barely five feet by four and six feet in depth. Surely it was not a royal tomb, Carter decided.

Surely it was, Davis announced, shrugging off its unroyal proportions: The insignificant boy Tut, son of a despised heretic, would not have been given a grand burial. Among other evidence in the tomb, a strip of thick gold foil had been found, gilding torn off a royal chariot. Tut’s figure was engraved on the foil, riding in a chariot and shooting arrows at a target to which foreign captives were bound.

There was no mistaking the cartouche with Tut’s throne name inscribed in the middle—the basket for Neb, or “Lord of;” the dung beetle for Kheperure, or “Manifestation of” (literally: “Becoming”); and the disk for Ra, or “Sun”: Nebkheperure, Lord of the Sun’s Manifestation.

Davis announced that now everything that was to be found in

the Valley had been found. He “fears the Valley is now exhausted,” as he put it, and he gave up the now worthless concession.

Which Carter tried to convince Carnarvon to take up. Carnarvon hesitated. A long list of experts agreed with Davis—the Valley had been “done.” The consensus of archaeological opinion was against Carter; and even Maspero, renowned for his scholarship, suggested that Carnarvon would do better to dig elsewhere.

Carter insisted that Davis was wrong, that the gold foil with Tut’s name was not original to the tomb. It had most probably been carried in by later flooding, he argued. Every instinct told him that #58 was not a royal burial, but an ordinary pit tomb like nearby #54, also stumbled upon by Davis some years earlier.

At the time, Davis had attached no importance to #54 with its meager contents: satchels of a mineral used in embalming (natron), earthenware pots, mummy bandages, and floral wreaths thrown together with bones from an ancient funeral feast. Davis had torn to bits some of the floral wreaths at a dinner party and given away the worthless find for the asking—the asker being Herbert Winlock of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, who wanted to take the objects back to America for further study (the find can still be seen in a small room in the Met).

But if Davis was not interested in the undramatic contents of #54, Carter was. He noted the Eighteenth Dynasty pots (Petrie’s training) and took to heart Winlock’s opinion that the material had been used in a royal burial. In addition, Carter pointed out to Carnarvon that a green faience cup bearing Tut’s name had been found behind a boulder in “the triangle.”

If Davis was wrong and Tut’s tomb still remained to be discovered, and if Tut was in fact buried in the Valley (as the embalming cache and faience cup seemed to indicate), then, Carter argued, there was a good chance it was unplundered. He pointed to the lists of the ancient priests of Amun who had overseen the royal necropolis. During Ramesside times, they had recorded the royal

tombs that had been broken into, the royal burials that had to be “renewed”—Carter could reel them off by heart and knew that Tutankhamun’s name was not among them.

Carnarvon took his time deciding. Once he backed Carter, he would back him all the way, but it was daunting to put up a fortune—not to mention being thought a fool by those in the know—on the basis of some old mummy rags and lists drawn up by priests three thousand years ago. Any day a donkey’s leg could go through the ground and in some underground cache or other another ancient list of plundered tombs might be found with Tutankhamun’s name on top.