Influence: Science and Practice (15 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

So the toy manufacturers are faced with a dilemma: how to keep sales high during the peak season and, at the same time, retain a healthy demand for toys in the immediately following months. Their difficulty certainly doesn’t lie in motivating kids to want more toys after Christmas. The problem lies in motivating postholiday spent-out parents to buy another plaything for their already toy-glutted children. What could the toy companies possibly do to produce that unlikely behavior? Some have tried greatly increased advertising campaigns, others have reduced prices during the slack period, but neither of those standard sales devices has proved successful. Both tactics are costly, and have been ineffective in increasing sales to desired levels. Parents are simply not in a toy-buying mood, and the influences of advertising or reduced expense are not enough to shake that stony resistance.

Certain large toy manufacturers, however, think they have found a solution. It’s an ingenious one, involving no more than a normal advertising expense and an understanding of the powerful pull of the need for consistency. My first hint of the way the toy companies’ strategy worked came after I fell for it and then, in true patsy form, fell for it again.

It was January, and I was in the town’s largest toy store. After purchasing all too many gifts there for my son a month before, I had sworn not to enter that store or any like it for a long, long time. Yet there I was, not only in the diabolic place but also in the process of buying my son another expensive toy—a big, electric road-race set. In front of the road-race display I happened to meet a former neighbor who was buying his son the same toy. The odd thing was that we almost never saw each other anymore. In fact, the last time had been a year earlier in the same store when we were both buying our sons an expensive post-Christmas gift—that time a robot that walked, talked, and laid waste. We laughed about our strange pattern of seeing each other only once a year at the same time, in the same place, while doing the same thing. Later that day, I mentioned the coincidence to a friend who, it turned out, had once worked in the toy business.

“No coincidence,” he said knowingly.

“What do you mean, ‘No coincidence’?”

“Look,” he said, “let me ask you a couple of questions about the road-race set you bought this year. First, did you promise your son that he’d get one for Christmas?”

“Well, yes I did. Christopher had seen a bunch of ads for them on the Saturday morning cartoon shows and said that was what he wanted for Christmas. I saw a couple of ads myself and it looked like fun; so I said OK.”

“Strike one,” he announced. “Now for my second question. When you went to buy one, did you find all the stores sold out?”

“That’s right, I did! The stores said they’d ordered some but didn’t know when they’d get any more in. So I had to buy Christopher some other toys to make up for the road-race set. But how did you know?”

“Strike two,” he said. “Just let me ask one more question. Didn’t this same sort of thing happen the year before with the robot toy?”

“Wait a minute . . . you’re right. That’s just what happened. This is incredible. How did you know?”

“No psychic powers; I just happen to know how several of the big toy companies jack up their January and February sales. They start prior to Christmas with attractive TV ads for certain special toys. The kids, naturally, want what they see and extract Christmas promises for these items from their parents. Now here’s where the genius of the companies’ plan comes in: They

undersupply

the stores with the toys they’ve gotten the parents to promise. Most parents find those toys sold out and are forced to substitute other toys of equal value. The toy manufacturers, of course, make a point of supplying the stores with plenty of these substitutes. Then, after Christmas, the companies start running the ads again for the other, special toys. That juices up the kids to want those toys more than ever. They go running to their parents whining, ‘You promised, you promised,’ and the adults go trudging off to the store to live up dutifully to their words.”

“Where,” I said, beginning to seethe now, “they meet other parents they haven’t seen for a year, falling for the same trick, right?”

No Pain, No (Ill-gotten) Gain

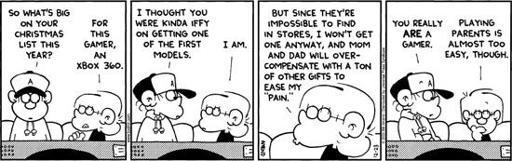

Jason, the gamer in this cartoon, has gotten the tactic for holiday gift success right, but, I think he’s gotten the reason for that success wrong. My own experience tells me that his parents will overcompensate with other gifts not so much to ease his pain but to ease their own pain at having to break their promise to him.

FOXTROT ©

2005 Bill Amend. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

“Right. Uh, where are you going?”

“I’m going to take the road-race set right back to the store.” I was so angry I was nearly shouting.

“Wait. Think for a minute first. Why did you buy it this morning?”

“Because I didn’t want to let Christopher down and because I wanted to teach him that promises are to be lived up to.”

“Well, has any of that changed? Look, if you take his toy away now, he won’t understand why. He’ll just know that his father broke a promise to him. Is that what you want?”

“No,” I said, sighing, “I guess not. So, you’re telling me that the toy companies doubled their profits on me for the past two years, and I never even knew it; and now that I do, I’m still trapped—by my own words. So, what you’re really telling me is, ‘Strike three.’ ” He nodded, “And you’re out.”

In the years since, I have observed a variety of parental toy-buying sprees similar to the one I experienced during that particular holiday season—for Beanie Babies, Tickle Me Elmo dolls, Furbies, Xboxes, Wii consoles etc. But, historically, the one that best fits the pattern is that of the Cabbage Patch Kids, $25 dolls that were promoted heavily during mid-1980s Christmas seasons but were woefully under-supplied to stores. Some of the consequences were a government false advertising charge against the Kids’ maker for continuing to advertise dolls that were not available; frenzied groups of adults battling at toy outlets or paying up to $700 apiece at auction for dolls they had

promised

their children; and an annual $150 million in sales that extended well beyond the Christmas months. During the 1998 holiday season, the least available toy that everyone wanted was the Furby, created by a division of toy giant Hasbro. When asked what frustrated, Furby-less parents should tell their kids, a Hasbro spokeswoman advised the kind of promise that has profited toy manufacturers for decades, “I’ll try, but if I can’t get it for you now, I’ll get it for you later” (Tooher, 1998).

Commitment Is the Key

Once we realize that the power of consistency is formidable in directing human action, an important practical question immediately arises: How is that force engaged? What produces the

click

that activates the

whirr

of the powerful consistency tape? Social psychologists think they know the answer: commitment. If I can get you to make a commitment (that is, to take a stand, to go on record), I will have set the stage for your automatic and ill-considered consistency with that earlier commitment. Once a stand is taken, there is a natural tendency to behave in ways that are stubbornly consistent with the stand. Even preliminary leanings that occur before a final decision has to be made can bias us toward consistent subsequent choices (Brownstein, 2003; Brownstein, Read, & Simon, 2004; Russo, Carlson, & Meloy, 2006).

As we’ve already seen, social psychologists are not the only ones who understand the connection between commitment and consistency. Commitment strategies are aimed at us by compliance professionals of nearly every sort. Each of the

strategies is intended to get us to take some action or make some statement that will trap us into later compliance through consistency pressures. Procedures designed to create commitment take various forms. Some are bluntly straightforward; others are among the most subtle compliance tactics we will encounter. On the blunt side, consider the approach of Jack Stanko, used-car sales manager for an Albuquerque auto dealership. While leading a session called “Used Car Merchandising” at a National Auto Dealers Association convention in San Francisco, he advised 100 sales-hungry dealers as follows: “Put ’em on paper. Get the customer’s OK on paper. Get the money up front. Control ’em. Control the deal. Ask ’em if they would buy the car right now if the price is right. Pin ’em down” (Rubinstein, 1985). Obviously, Mr. Stanko—an expert in these matters—believes that the way to customer compliance is through their commitments, thereby to “control ‘em” for profit.

Commitment practices involving substantially more finesse can be just as effective. For instance, suppose you wanted to increase the number of people in your area who would agree to go door-to-door collecting donations for your favorite charity. You would be wise to study the approach taken by social psychologist Steven J. Sherman. He simply called a sample of Bloomington, Indiana, residents as part of a survey he was taking and asked them to predict what they would say if asked to spend three hours collecting money for the American Cancer Society. Of course, not wanting to seem uncharitable to the survey-taker or to themselves, many of these people said that they would volunteer. The consequence of this subtle commitment procedure was a 700 percent increase in volunteers when, a few days later, a representative of the American Cancer Society did call and ask for neighborhood canvassers (Sherman, 1980). Using the same strategy, but this time asking citizens to predict whether they would vote on election day, other researchers have been able to increase significantly the turnout at the polls among those called (Greenwald, Carnot, Beach, & Young, 1987; Spangenberg & Greenwald, in press). Courtroom combatants appear to have adopted this practice of extracting a lofty initial commitment that is designed to spur future consistent behavior. When screening potential jurors before a trial, Jo-Ellen Demitrius, the woman currently reputed to be the best consultant in the business of jury selection asks an artful question: “If you were the only person who believed in my client’s innocence, could you withstand the pressure of the rest of the jury to change your mind?” How could any self-respecting prospective juror say no? And, having made the public promise, how could any self-respecting selected juror repudiate it later?

Perhaps an even more crafty commitment technique has been developed by telephone solicitors for charity. Have you noticed that callers asking you to contribute to some cause or another these days seem to begin things by inquiring about your current health and well-being? “Hello, Mr./Ms. Targetperson,” they say. “How are you feeling this evening?,” or “How are you doing today?” The caller’s intent with this sort of introduction is not merely to seem friendly and caring. It is to get you to respond—as you normally do to such polite, superficial inquiries—with a polite, superficial comment of your own: “Just fine” or “Real good” or “I’m doing

great, thanks.” Once you have publicly stated that all is well, it becomes much easier for the solicitor to corner you into aiding those for whom all is not well: “I’m glad to hear that, because I’m calling to ask if you’d be willing to make a donation to help out the unfortunate victims of . . .”

The theory behind this tactic is that people who have just asserted that they are doing/feeling fine—even as a routine part of a sociable exchange—will consequently find it awkward to appear stingy in the context of their own admittedly favored circumstances. If all this sounds a bit far-fetched, consider the findings of consumer researcher Daniel Howard (1990), who put the theory to test. Residents of Dallas, Texas, were called on the phone and asked if they would agree to allow a representative of the Hunger Relief Committee to come to their homes to sell them cookies, the proceeds from which would be used to supply meals for the needy. When tried alone, that request (labeled the standard solicitation approach) produced only 18 percent agreement. However, if the caller initially asked, “How are you feeling this evening?” and waited for a reply before proceeding with the standard approach, several noteworthy things happened. First, of the 120 individuals called, most (108) gave the customary favorable reply (“Good,” “Fine,” “Real well,” etc.). Second, 32 percent of the people who got the How-are-you-feeling-tonight question agreed to receive the cookie seller at their homes, nearly twice the success rate of the standard solicitation approach. Third, true to the consistency principle, almost everyone (89 percent) who agreed to such a visit did in fact make a cookie purchase when contacted at home.

The question of what makes a commitment effective has numerous answers. A variety of factors affects the ability of a commitment to constrain our future behavior. One large-scale program designed to produce compliance illustrates how several of the factors work. The remarkable thing about this program is that it was systematically employing these factors decades ago, well before scientific research had identified them.

During the Korean War, many captured American soldiers found themselves in prisoner-of-war camps run by the Chinese Communists. It became clear early in the conflict that the Chinese treated captives quite differently than did their allies, the North Koreans, who favored harsh punishment to gain compliance. Specifically avoiding the appearance of brutality, the Red Chinese engaged in what they termed their “lenient policy,” which was, in reality, a concerted and sophisticated psychological assault on their captives. After the war, American psychologists questioned the returning prisoners intensively to determine what had occurred, in part because of the unsettling success of some aspects of the Chinese program. For example, the Chinese were very effective in getting Americans to inform on one another, in striking contrast to the behavior of American POWs in World War II. For this reason, among others, escape plans were quickly uncovered and the escapes themselves almost always unsuccessful. “When an escape did occur,” wrote psychologist Edgar Schein (1956), a principal American investigator of the Chinese indoctrination program in Korea, “the Chinese usually recovered the man easily by offering a bag of rice to anyone turning him in.” In fact, nearly all American prisoners in the Chinese camps are said to have collaborated with the enemy in one way or another.

1