Influence: Science and Practice (19 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Exposure to cold.

On a winter night, Frederick Bronner, a California junior college student, was taken 3,000 feet up and 10 miles into the hills of a national forest by his prospective fraternity brothers. Left to find his way home wearing only a thin sweat shirt and slacks, Fat Freddy, as he was called, shivered in a frigid wind until he tumbled down a steep ravine, fracturing bones and hurting his head. Prevented by his injuries from going on, he huddled there against the cold until he died of exposure.

Thirst.

Two Ohio State University freshmen found themselves in the “dungeon” of their prospective fraternity house after breaking the rule requiring all pledges to crawl into the dining area prior to Hell Week meals. Once locked in the house storage closet, they were given only salty foods to eat for nearly two days. Nothing was provided for drinking purposes except a pair of plastic cups in which they could catch their own urine.

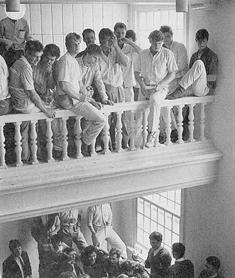

Hazy Daze

Initiation ceremonies are common to all manner of exclusive groups, although the type of initiation experience can vary widely. A Dutch debating society (left) hazes its initiates by requiring public songs and chants, while a Texas street gang (below) pummels a new member.

Eating of unsavory foods.

At Kappa Sigma house on the campus of the University of Southern California, the eyes of eleven pledges bulged when they saw the sickening task before them. Eleven quarter-pound slabs of raw liver lay on a tray. Thick cut and soaked in oil, each was to be swallowed whole, one to a boy. Gagging and choking repeatedly, young Richard Swanson failed three times to down his piece. Determined to succeed, he finally got the oilsoaked meat into his throat where it lodged and, despite all efforts to remove it, killed him.

Punishment.

In Wisconsin, a pledge who forgot one section of a ritual incantation to be memorized by all initiates was punished for his error. He was required to keep his feet under the rear legs of a folding chair while the heaviest of his fraternity brothers sat down and drank a beer. Although the pledge did not cry out during the punishment, a bone in each of his feet was broken.

Threats of death.

A pledge of Zeta Beta Tau fraternity was taken to a beach area of New Jersey and told to dig his “own grave.” Seconds after he complied with orders to lie flat in the finished hole, the sides collapsed, suffocating him before his prospective fraternity brothers could dig him out.

There is another striking similarity between the initiation rites of tribal and fraternal societies: They simply will not die. Resisting all attempts to eliminate or suppress them, such hazing practices have been phenomenally resilient. Authorities, in the form of colonial governments or university administrations, have tried threats, social pressures, legal actions, banishments, bribes, and bans to persuade groups to remove the hazards and humiliations from their initiation ceremonies. None has been successful. Oh, there may be a change while the authority is watching closely, but this is usually more apparent than real—the harsher trials occurring under more secret circumstances until the pressure is off when they can surface again.

On some college campuses, officials have tried to eliminate dangerous hazing practices by substituting a “Help Week” of civic service or by taking direct control of the initiation rituals. When such attempts are not slyly circumvented by fraternities, they are met with outright physical resistance. For example, in the aftermath of Richard Swanson’s choking death at USC, the university president issued new rules requiring that all pledging activities be reviewed by school authorities before going into effect and that adult advisers be present during initiation ceremonies. According to one national magazine, “the new ‘code’ set off a riot so violent that city police and fire detachments were afraid to enter campus.”

Resigning themselves to the inevitable, other college representatives have given up on the possibility of abolishing the degradations of Hell Week. “If hazing is a universal human activity, and every bit of evidence points to this conclusion, you most likely won’t be able to ban it effectively. Refuse to allow it openly and it will go underground. You can’t ban sex, you can’t prohibit alcohol, and you probably can’t eliminate hazing!” (Gordon & Gordon, 1963).

What is it about hazing practices that make them so precious to these societies? What could make the groups want to evade, undermine, or contest any effort to ban the degrading and perilous features of their initiation rights? Some have argued that the groups themselves are composed of psychological or social miscreants whose twisted needs demand that others be harmed and humiliated. The evidence, however, does not support such a view. Studies done on the personality traits of fraternity members, for instance, show them to be, if anything, slightly healthier than other college students in their psychological adjustment (for a review, see C. S.

Johnson, 1972). Similarly, fraternities are known for their willingness to engage in beneficial community projects for the general social good. What they are not willing to do, however, is substitute these projects for their initiation ceremonies. One survey at the University of Washington (Walker, 1967) found that, of the fraternity chapters examined, most had a type of Help Week tradition but that this community service was

in addition

to Hell Week. In only one case was such service directly related to initiation procedures.

The picture that emerges of the perpetrators of hazing practices is of normal individuals who tend to be psychologically stable and socially concerned but who become aberrantly harsh as a group at only one time—immediately before the admission of new members to the society. The evidence, then, points to the ceremony as the culprit. There must be something about its rigors that is vital to the group. There must be some function to its harshness that the society will fight relentlessly to maintain. What?

My own view is that the answer appeared in 1959 in the results of a study little known outside of social psychology. A pair of young researchers, Elliot Aronson and Judson Mills, decided to test their observation that “persons who go through a great deal of trouble or pain to attain something tend to value it more highly than persons who attain the same thing with a minimum of effort.” The real stroke of inspiration came in their choice of the initiation ceremony as the best place to examine this possibility. They found that college women who had to endure a severely embarrassing initiation ceremony in order to gain access to a sex discussion group convinced themselves that their new group and its discussions were extremely valuable, even though Aronson and Mills had rehearsed the other group members to be as “worthless and uninteresting” as possible. Different coeds who went through a much milder initiation ceremony or went through no initiation at all, were decidedly less positive about the “worthless” new group they had joined. Additional research showed the same results when coeds were required to endure pain rather than embarrassment to get into a group (Gerard & Mathewson, 1966). The more electric shock a woman received as part of the initiation ceremony, the more she later persuaded herself that her new group and its activities were interesting, intelligent, and desirable.