Influence: Science and Practice (22 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Strangely enough, though, when the publicity factor was no longer a possibility, these families did not merely maintain their fuel-saving effort, they heightened it. Any of a number of interpretations could be offered for that still stronger effort, but I have a favorite. In a way, the opportunity to receive newspaper publicity had prevented the homeowners from fully owning their commitment to conservation. Of all the reasons supporting the decision to try to save fuel, it was the only one that had come from the outside; it was the only one preventing the homeowners from thinking that they were conserving gas because they believed in it. So when the letter arrived canceling the publicity agreement, it removed the only impediment to these residents’ images of themselves as fully concerned, energy-conscious citizens.

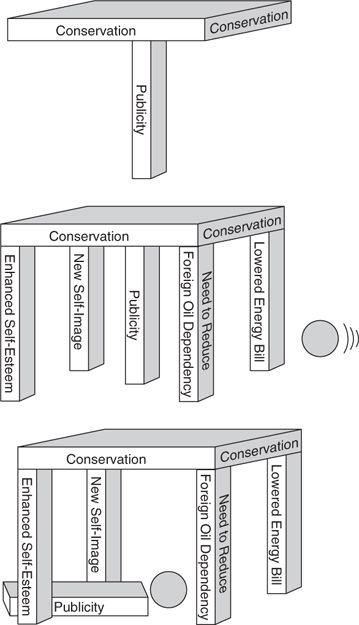

Figure 3.2

The Low-Ball for the Long-Term

In this illustration of the Iowa energy research, we can see how the original conservation effort rested on the promise of publicity

(top)

. Before long, however, this energy commitment led to the sprouting of new, self-generated supports, allowing the research team to throw its low-ball

(middle).

The consequence was a persisting level of conservation that stood firmly on its own legs after the initial publicity prop had been knocked down

(bottom)

.

This unqualified, new self-image then pushed them to even greater heights of conservation. Much like Sara, they appeared to have become committed to a choice through an initial inducement and were still more dedicated to it after the inducement had been removed.

5

5

Fortunately, it is not necessary to use so deceptive an approach as the low-ball technique to employ the power of the commitment/consistency principle in public-service campaigns. An impressive series of studies by Richard Katzev and his students at Reed College has demonstrated the effectiveness of commitment tactics like written pledges and foot-in-the-door procedures in increasing such energy conservation behaviors as recycling, electricity usage, and bus ridership (Bachman & Katzev, 1982; Katzev & Johnson, 1983, 1984; Katzev & Pardini, 1988; Pardini & Katzev, 1983-84).

Defense

The only effective defense I know against the weapons of influence embodied in the combined principles of commitment and consistency is an awareness that, although consistency is generally good, even vital, there is a foolish, rigid variety to be shunned. We must be wary of the tendency to be automatically and unthinkingly consistent, for it lays us open to the maneuvers of those who want to exploit the mechanical commitment-consistency sequence for profit.

Since automatic consistency is so useful in allowing us an economical and appropriate way of behaving most of the time, however, we can’t decide merely to eliminate it from our lives altogether. The results would be disastrous. If, rather than whirring along in accordance with our prior decisions and deeds, we stopped to think through the merits of each new action before performing it, we would never have time to accomplish anything significant. We need even that dangerous, mechanical brand of consistency. The only way out of the dilemma is to know when such consistency is likely to lead to a poor choice. There are certain signals– two separate kinds of signals—to tip us off. We register each type in a different part of our bodies.

Stomach Signs

The first signal is easy to recognize. It occurs right in the pit of our stomachs when we realize we are trapped into complying with a request we

know

we don’t want to perform. It has happened to me a hundred times. An especially memorable instance, though, took place on a summer evening well before I began to study compliance tactics. I answered my doorbell to find a stunning young woman dressed in shorts and a revealing halter top. I noticed, nonetheless, that she was carrying a clipboard and was asking me to participate in a survey. Wanting to make a favorable impression, I agreed and, I do admit, stretched the truth in my interview answers in order to present myself in the most positive light. Our conversation went as follows:

Stunning Young Woman:

Hello! I’m doing a survey on the entertainment habits of city residents, and I wonder if you could answer a few questions for me.

Cialdini:

Do come in.

SYW:

Thank you. I’ll just sit right here and begin. How many times per week would you say you go out to dinner?

C:

Oh, probably three, maybe four times a week. Whenever I can, really; I love fine restaurants.

SYW:

How nice. And do you usually order wine with your dinner?

C:

Only if it’s imported.

SYW:

I see. What about movies? Do you go to the movies much?

C:

The cinema? I can’t get enough of good films. I especially like the sophisticated kind with the words on the bottom of the screen. How about you? Do you like to see films?

SYW:

Uh . . . yes, I do. But let’s get back to the interview. Do you go to many concerts?

C:

Definitely. The symphonic stuff mostly, of course. But I do enjoy a quality pop group as well.

SYW:

(writing rapidly).

Great! just one more question. What about touring performances by theatrical or ballet companies? Do you see them when they’re in town?

C:

Ah, the ballet—the movement, the grace, the form—I love it. Mark me down as

loving

the ballet. See it every chance I get.

SYW:

Fine. Just let me recheck my figures here for a moment, Mr. Cialdini.

C:

Actually, it’s Dr. Cialdini. But that sounds so formal. Why don’t you call me Bob?

SYW:

All right,

Bob

. From the information you’ve already given me, I’m pleased to say you could save up to $1,200 a year by joining

Clubamerica!

A small membership fee entitles you to discounts on most of the activities you’ve mentioned. Surely someone as socially vigorous as yourself would want to take advantage of the tremendous savings our company can offer on all the things you’ve already told me you do.

C:

(trapped like a rat).

Well . . . uh . . . I . . . uh . . . I guess so.

I remember quite well feeling my stomach tighten as I stammered my agreement. It was a clear call to my brain, “Hey, you’re being taken here!” But I couldn’t see a way out. I had been cornered by my own words. To decline her offer at that point would have meant facing a pair of distasteful alternatives: If I tried to back out by protesting that I was not actually the man-about-town I had claimed to be during the interview, I would come off a liar; trying to refuse without that protest would make me come off a fool for not wanting to save $1,200. I bought the entertainment package, even though I knew I had been set up. The need to be consistent with what I had already said snared me.

No more, though. I listen to my stomach these days, and I have discovered a way to handle people who try to use the consistency principle on me. I just tell them exactly what they are doing. This tactic has become the perfect counterattack for me. Whenever my stomach tells me I would be a sucker to comply with a request merely because doing so would be consistent with some prior commitment I was tricked into, I relay that message to the requester. I don’t try to deny the importance of consistency; I just point out the absurdity of foolish consistency. Whether, in response, the requester shrinks away guiltily or retreats in bewilderment, I am content. I have won; an exploiter has lost.

I sometimes think about the way it would be if that stunning young woman of years ago were to try to sell me an entertainment-club membership now. I have it all worked out. The entire interaction would be the same, except for the end:

SYW:

. . . Surely someone as socially vigorous as yourself would want to take advantage of the tremendous savings our company can offer on all the things you’ve already told me you do.

C:

(with great self-assurance).

Quite wrong. You see, I recognize what has gone on here. I know that your story about doing a survey was just a pretext for getting people to tell you how often they go out and that, under those circumstances, there is a natural tendency to exaggerate. And I refuse to allow myself to be locked into a mechanical sequence of commitment and consistency when I know it’s wrong-headed. No

click

,

whirr

for me.

SYW:

Huh?

C:

Okay, let me put it this way: (1) It would be stupid of me to spend money on something I don’t want. (2) I have it on excellent authority, direct from my stomach, that I don’t want your entertainment plan. (3) Therefore, if you still believe that I will buy it, you probably also still believe in the Tooth Fairy. Surely, someone as intelligent as yourself would be able to understand that.

SYW:

(trapped like a stunning young rat)

Well . . . uh . . . I . . . uh . . . I guess so.

Heart-of-Hearts Signs

Stomachs are not especially perceptive or subtle organs. Only when it is

obvious

that we are about to be conned are they likely to register and transmit that message. At other times, when it is not clear that we are being taken, our stomachs may never catch on. Under those circumstances we have to look elsewhere for a clue. The situation of my neighbor Sara provides a good illustration. She made an important commitment to Tim by canceling her prior marriage plans. The commitment has grown its own supports, so that even though the original reasons for the commitment are gone, she remains in harmony with it. She has convinced herself with newly formed reasons that she did the right thing, so she stays with Tim. It is not difficult to see why there would be no tightening in Sara’s stomach as a result. Stomachs tell us when we are doing something we think is wrong for us. Sara

thinks

no such thing. To her mind, she has chosen correctly and is behaving consistently with that choice.

Yet, unless I badly miss my guess, there is a part of Sara that recognizes her choice as a mistake and her current living arrangement as a brand of foolish consistency. Where, exactly, that part of Sara is located we can’t be sure, but our language does give it a name: heart of hearts. It is, by definition, the one place where we cannot fool ourselves. It is the place where none of our justifications, none of our rationalizations penetrate. Sara has the truth there, although right now she can’t hear its signal clearly through the noise and static of the new support apparatus she has erected.

If Sara has erred in her choice of Tim, how long can she go without clearly recognizing it, without having a massive heart-of-hearts attack? There is no telling. One thing is certain, however: As time passes, the various alternatives to Tim are disappearing. She had better determine soon whether she is making a mistake.

Easier said than done, of course. She must answer an extremely intricate question: “Knowing what I now know, if I could go back in time, would I make the same choice?” The problem lies in the “knowing what I now know” part of the question. Just what does she now know, accurately, about Tim? How much of what she thinks of him is the result of a desperate attempt to justify the commitment she made? She claims that, since her decision to take him back, he cares for her more, is trying hard to stop his excessive drinking, has learned to make a wonderful omelet, etc. Having tasted a couple of his omelets, I have my doubts. The important issue, though, is whether

she

believes these things, not just intellectually—but in her heart of hearts.

There may be a little device Sara can use to find out how much of her current satisfaction with Tim is real and how much is foolish consistency. Psychological evidence indicates that we experience our feelings toward something a split second before we can intellectualize about it (Murphy & Zajonc, 1993; van den Berg et al., 2006). My suspicion is that the message sent by the heart of hearts is a pure, basic feeling. Therefore, if we train ourselves to be attentive, we should register the feeling ever so slightly before our cognitive apparatus engages. According to this approach, were Sara to ask herself the crucial “would I make the same choice again?” question, she would be well advised to look for and trust the first flash of feeling she experienced in response. It would likely be the signal from her heart of hearts, slipping through undistorted just before the means by which she could kid herself flooded in.

6