Irish Fairy Tales (28 page)

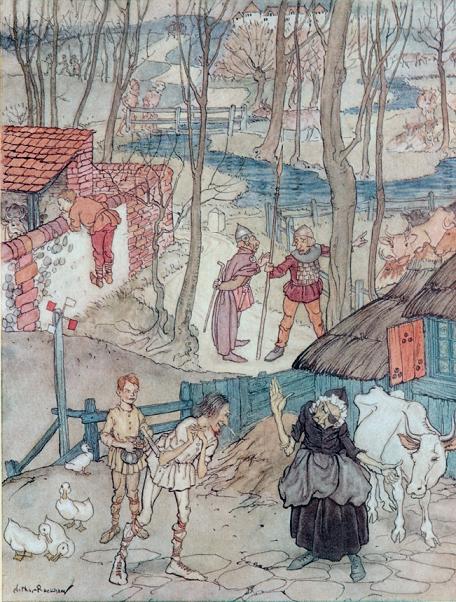

They offered a cow for each leg of her cow, but she would not accept that

offer unless Fiachna went bail for the payment

Chapter 6

A

year passed, and one day as he was sitting at judgement there came a great noise from without, and this noise was so persistent that the people and suitors were scandalised, and Fiachna at last ordered that the noisy person should be brought before him to be judged.

It was done, and to his surprise the person turned out to be the Black Hag.

She blamed him in the court before his people, and complained that he had taken away her cow, and that she had not been paid the four cows he had gone bail for, and she demanded judgement from him and justice.

“If you will consider it to be justice, I will give you twenty cows myself,” said Fiachna.

“I would not take all the cows in Ulster,” she screamed.

“Pronounce judgement yourself,” said the king, “and if I can do what you demand I will do it.” For he did not like to be in the wrong, and he did not wish that any person should have an unsatisfied claim upon him.

The Black Hag then pronounced judgement, and the king had to fulfil it.

“I have come,” said she, “from the east to the west; you must come from the west to the east and make war for me, and revenge me on the King of Lochlann.”

Fiachna had to do as she demanded, and, although it was with a heavy heart, he set out in three days' time for Lochlann, and he brought with him ten battalions.

He sent messengers before him to Big Eolgarg warning him of his coming, of his intention, and of the number of troops he was bringing; and when he landed Eolgarg met him with an equal force, and they fought together.

In the first battle three hundred of the men of Lochlann were killed, but in the next battle Eolgarg Mor did not fight fair, for he let some venomous sheep out of a tent, and these attacked the men of Ulster and killed nine hundred of them.

So vast was the slaughter made by these sheep and so great the terror they caused, that no one could stand before them, but by great good luck there was a wood at hand, and the men of Ulster, warriors and princes and charioteers, were forced to climb up the trees, and they roosted among the branches like great birds, while the venomous sheep ranged below bleating terribly and tearing up the ground.

Fiachna Finn was also sitting in a tree, very high up, and he was disconsolate.

“We are disgraced!” said he.

“It is very lucky,” said the man in the branch below, “that a sheep cannot climb a tree.”

“We are disgraced for ever!” said the King of Ulster.

“If those sheep learn how to climb, we are undone surely,” said the man below.

“I will go down and fight the sheep,” said Fiachna. But the others would not let the king go.

“It is not right,” they said, “that you should fight sheep.”

“Some one must fight them,” said Fiachna Finn, “but no more of my men shall die until I fight myself; for if I am fated to die, I will die and I cannot escape it, and if it is the sheep's fate to die, then die they will; for there is no man can avoid destiny, and there is no sheep can dodge it either.”

“Praise be to god!” said the warrior that was higher up.

“Amen!” said the man who was higher than he, and the rest of the warriors wished good luck to the king.

He started then to climb down the tree with a heavy heart, but while he hung from the last branch and was about to let go, he noticed a tall warrior walking towards him. The king pulled himself up on the branch again and sat dangle-legged on it to see what the warrior would do.

The stranger was a very tall man, dressed in a green cloak with a silver brooch at the shoulder. He had a golden band about his hair and golden sandals on his feet, and he was laughing heartily at the plight of the men of Ireland.

Chapter 7

I

t is not nice of you to laugh at us,” said Fiachna Finn.

“Who could help laughing at a king hunkering on a branch and his army roosting around him like hens?” said the stranger.

“Nevertheless,” the king replied, “it would be courteous of you not to laugh at misfortune.”

“We laugh when we can,” commented the stranger, “and are thankful for the chance.”

“You may come up into the tree,” said Fiachna, “for I perceive that you are a mannerly person, and I see that some of the venomous sheep are charging in this direction. I would rather protect you,” he continued, “than see you killed; for,” said he lamentably, “I am getting down now to fight the sheep.”

“They will not hurt me,” said the stranger.

“Who are you?” the king asked.

“I am Manannán, the son of Lir.”

Fiachna knew then that the stranger could not be hurt.

“What will you give me if I deliver you from the sheep?” asked Manannán.

“I will give you anything you ask, if I have that thing.”

“I ask the rights of your crown and of your household for one day.”

Fiachna's breath was taken away by that request, and he took a little time to compose himself, then he said mildly:

“I will not have one man of Ireland killed if I can save him. All that I have they give me, all that I have I give to them, and if I must give this also, then I will give this, although it would be easier for me to give my life.”

“That is agreed,” said Mannanán.

He had something wrapped in a fold of his cloak, and he unwrapped and produced this thing.

It was a dog.

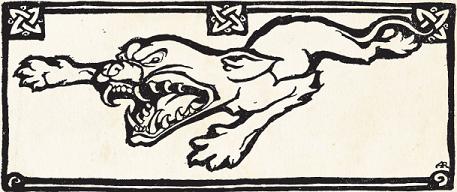

Now if the sheep were venomous, this dog was more venomous still, for it was fearful to look at. In body it was not large, but its head was of a great size, and the mouth that was shaped in that head was able to open like the lid of a pot. It was not teeth which were in that head, but hooks and fangs and prongs. Dreadful was that mouth to look at, terrible to look into, woeful to think about; and from it, or from the broad, loose nose that waggled above it, there came a sound which no word of man could describe, for it was not a snarl, nor was it a howl, although it was both of these. It was neither a growl nor a grunt, although it was both of these; it was not a yowl nor a groan, although it was both of these: for it was one sound made up of these sounds, and there was in it, too, a whine and a yelp, and a long-drawn snoring noise, and a deep purring noise, and a noise that was like the squeal of a rusty hinge, and there were other noises in it also.

“The gods be praised!” said the man who was in the branch above the king.

“What for this time?” said the king.

“Because that dog cannot climb a tree,” said the man.

And the man on a branch yet above him groaned out “Amen!”

“There is nothing to frighten sheep like a dog,” said Manannán, “and there is nothing to frighten these sheep like this dog.”

He put the dog on the ground then.

“Little dogeen, little treasure,” said he, “go and kill the sheep.”

And when he said that the dog put an addition and an addendum on to the noise he had been making before, so that the men of Ireland stuck their fingers into their ears and turned the whites of their eyes upwards, and nearly fell off their branches with the fear and the fright which that sound put into them.

It did not take the dog long to do what he had been ordered. He went forward, at first, with a slow waddle, and as the venomous sheep came to meet him in bounces, he then went to meet them in wriggles; so that in a while he went so fast that you could see nothing of him but a head and a wriggle. He dealt with the sheep in this way, a jump and a chop for each, and he never missed his jump and he never missed his chop. When he got his grip he swung round on it as if it was a hinge. The swing began with the chop, and it ended with the bit loose and the sheep giving its last kick. At the end of ten minutes all the sheep were lying on the ground, and the same bit was out of every sheep, and every sheep was dead.

“You can come down now,” said Manannán.

“That dog can't climb a tree,” said the man in the branch above the king warningly.

“Praise be to the gods!” said the man who was above him.

“Amen!” said the warrior who was higher up than that.

And the man in the next tree said:

“Don't move a hand or a foot until the dog chokes himself to death on the dead meat.”

The dog, however, did not eat a bit of the meat. He trotted to his master, and Manannán took him up and wrapped him in his cloak.

“Now you can come down,” said he.

“I wish that dog was dead!” said the king.

But he swung himself out of the tree all the same, for he did not wish to seem frightened before Manannán.

“You can go now and beat the men of Lochlann,” said Manannán. “You will be King of Lochlann before nightfall.”

“I wouldn't mind that,” said the king.

“It's no threat,” said Manannán.

The son of Lir turned then and went away in the direction of Ireland to take up his one-day rights, and Fiachna continued his battle with the Lochlannachs.

He beat them before nightfall, and by that victory he became King of Lochlann and King of the Saxons and the Britons.

He gave the Black Hag seven castles with their territories, and he gave her one hundred of every sort of cattle that he had captured. She was satisfied.

Then he went back to Ireland, and after he had been there for some time his wife gave birth to a son.

Chapter 8

Y

ou have not told me one word about Duv Laca,” said the Flame Lady reproachfully.

“I am coming to that,” replied Mongan.

He motioned towards one of the great vats, and wine was brought to him, of which he drank so joyously and so deeply that all people wondered at his thirst, his capacity, and his jovial spirits.

“Now, I will begin again.”

Said Mongan:

There was an attendant in Fiachna Finn's palace who was called An Dáv, and the same night that Fiachna's wife bore a son, the wife of An Dáv gave birth to a son also. This latter child was called mac an Dáv, but the son of Fiachna's wife was named Mongan.

“Ah!” murmured the Flame Lady.

The queen was angry. She said it was unjust and presumptuous that the servant should get a child at the same time that she got one herself, but there was no help for it, because the child was there and could not be obliterated.

Now this also must be told.

There was a neighbouring prince called Fiachna Duv, and he was the ruler of the Dal Fiatach. For a long time he had been at enmity and spiteful warfare with Fiachna Finn; and to this Fiachna Duv there was born in the same night a daughter, and this girl was named Duv Laca of the White Hand.

“Ah!” cried the Flame Lady.

“You see!” said Mongan, and he drank anew and joyously of the fairy wine.

In order to end the trouble between Fiachna Finn and Fiachna Duv the babies were affianced to each other in the cradle on the day after they were born, and the men of Ireland rejoiced at that deed and at that news. But soon there came dismay and sorrow in the land, for when the little Mongan was three days old his real father, Manannán the son of Lir, appeared in the middle of the palace. He wrapped Mongan in his green cloak and took him away to rear and train in the Land of Promise, which is beyond the sea that is at the other side of the grave.