Irish Fairy Tales (31 page)

Mongan then took on himself the form of Tibraidè and he turned mac an Dáv into the shape of the clerk.

“My head has gone bald,” said the servant in a whisper.

“That is part of it,” replied Mongan.

“So long as we know!” said mac an Dáv.

They went on then to meet the King of Leinster.

Chapter 16

T

hey met him near the place where the games were played.

“Good my soul, Tibraidè!” cried the King of Leinster, and he gave Mongan a kiss. Mongan kissed him back again.

“Amen, amen,” said mac an Dáv.

“What for?” said the King of Leinster.

And then mac an Dáv began to sneeze, for he didn't know what for.

“It is a long time since I saw you, Tibraidè,” said the king, “but at this minute I am in great haste and hurry. Go you on before me to the fortress, and you can talk to the queen that you'll find there, she that used to be the King of Ulster's wife. Kevin Cochlach, my charioteer, will go with you, and I will follow you myself in a while.”

The King of Leinster went off then, and Mongan and his servant went with the charioteer and the people.

Mongan read away out of the book, for he found it interesting, and he did not want to talk to the charioteer, and mac an Dáv cried amen, amen, every time that Mongan took his breath. The people who were going with them said to one another that mac an Dáv was a queer kind of clerk, and that they had never seen any one who had such a mouthful of amens.

But in a while they came to the fortress, and they got into it without any trouble, for Kevin Cochlach, the king's charioteer, brought them in. Then they were led to the room where Duv Laca was, and as he went into that room Mongan shut his eyes, for he did not want to look at Duv Laca while other people might be looking at him.

“Let everybody leave this room, while I am talking to the queen,” said he; and all the attendants left the room, except one, and she wouldn't go, for she wouldn't leave her mistress.

Then Mongan opened his eyes and he saw Duv Laca, and he made a great bound to her and took her in his arms, and mac an Dáv made a savage and vicious and terrible jump at the attendant, and took her in his arms, and bit her ear and kissed her neck and wept down into her back.

“Go away,” said the girl, “unhand me, villain,” said she.

“I will not,” said mac an Dáv, “for I'm your own husband, I'm your own mac, your little mac, your macky-wac-wac.” Then the attendant gave a little squeal, and she bit him on each ear and kissed his neck and wept down into his back, and said that it wasn't true and that it was.

Chapter 17

B

ut they were not alone, although they thought they were. The hag that guarded the jewels was in the room. She sat hunched up against the wall, and as she looked like a bundle of rags they did not notice her. She began to speak then.

“Terrible are the things I see,” said she. “Terrible are the things I see.”

Mongan and his servant gave a jump of surprise, and their two wives jumped and squealed. Then Mongan puffed out his cheeks till his face looked like a bladder, and he blew a magic breath at the hag, so that she seemed to be surrounded by a fog, and when she looked through that breath everything seemed to be different to what she had thought. Then she began to beg everybody's pardon.

“I had an evil vision,” said she, “I saw crossways. How sad it is that I should begin to see the sort of things I thought I saw.”

“Sit in this chair, mother,” said Mongan, “and tell me what you thought you saw,” and he slipped a spike under her, and mac an Dáv pushed her into the seat, and she died on the spike.

Just then there came a knocking at the door. Mac an Dáv opened it, and there was Tibraidè standing outside, and twenty-nine of his men were with him, and they were all laughing.

“A mile was not half enough,” said mac an Dáv reproachfully.

The Chamberlain of the fortress pushed into the room and he stared from one Tibraidè to the other.

“This is a fine growing year,” said he. “There never was a year when Tibraidès were as plentiful as they are this year. There is a Tibraidè outside and a Tibraidè inside, and who knows but there are some more of them under the bed. The place is crawling with them,” said he.

Mongan pointed at Tibraidè.

“Don't you know who that is?” he cried.

“I know who he says he is,” said the Chamberlain.

“Well, he is Mongan,” said Mongan, “and these twenty-nine men are twenty-nine of his nobles from Ulster.”

At that news the men of the household picked up clubs and cudgels and every kind of thing that was near, and made a violent and woeful attack on Tibraidè's men. The King of Leinster came in then, and when he was told Tibraidè was Mongan he attacked them as well, and it was with difficulty that Tibraidè got away to Cell Camain with nine of his men and they all wounded.

The King of Leinster came back then. He went to Duv Laca's room.

“Where is Tibraidè?” said he.

“It wasn't Tibraidè was here,” said the hag who was still sitting on the spike, and was not half dead, “it was Mongan.”

“Why did you let him near you?” said the king to Duv Laca.

“There is no one has a better right to be near me than Mongan has,” said Duv Laca, “he is my own husband,” said she.

And then the king cried out in dismay:

“I have beaten Tibraidè's people.” He rushed from the room.

“Send for Tibraidè till I apologise,” he cried. “Tell him it was all a mistake. Tell him it was Mongan.”

Chapter 18

M

ongan and his servant went home, and (for what pleasure is greater than that of memory exercised in conversation?) for a time the feeling of an adventure well accomplished kept him in some contentment. But at the end of a time that pleasure was worn out, and Mongan grew at first dispirited and then sullen, and after that as ill as he had been on the previous occasion. For he could not forget Duv Laca of the White Hand, and he could not remember her without longing and despair.

It was in the illness which comes from longing and despair that he sat one day looking on a world that was black although the sun shone, and that was lean and unwholesome although autumn fruits were heavy on the earth and the joys of harvest were about him.

“Winter is in my heart,” quoth he, “and I am cold already.”

He thought too that some day he would die, and the thought was not unpleasant, for one half of his life was away in the territories of the King of Leinster, and the half that he kept in himself had no spice in it.

He was thinking in this way when mac an Dáv came towards him over the lawn, and he noticed that mac an Dáv was walking like an old man.

He took little slow steps, and he did not loosen his knees when he walked, so he went stiffly. One of his feet turned pitifully outwards, and the other turned lamentably in. His chest was pulled inwards, and his head was stuck outwards and hung down in the place where his chest should have been, and his arms were crooked in front of him with the hands turned wrongly, so that one palm was shown to the east of the world and the other one was turned to the west.

“How goes it, mac an Dáv?” said the king.

“Bad,” said mac an Dáv.

“Is that the sun I see shining, my friend?” the king asked.

“It may be the sun,” replied mac an Dáv, peering curiously at the golden radiance that dozed about them, “but maybe it's a yellow fog.”

“What is life at all?” said the king.

“It is a weariness and a tiredness,” said mac an Dáv. “It is a long yawn without sleepiness. It is a bee, lost at midnight and buzzing on a pane. It is the noise made by a tied-up dog. It is nothing worth dreaming about. It is nothing at all.”

“How well you explain my feelings about Duv Laca,” said the king.

“I was thinking about my own lamb,” said mac an Dáv. “I was thinking about my own treasure, my cup of cheeriness, and the pulse of my heart.” And with that he burst into tears.

“Alas!” said the king.

“But,” sobbed mac an Dáv, “what right have I to complain? I am only the servant, and although I didn't make any bargain with the King of Leinster or with any king of them all, yet my wife is gone away as if she was the consort of a potentate the same as Duv Laca is.”

Mongan was sorry then for his servant, and he roused himself.

“I am going to send you to Duv Laca.”

“Where the one is the other will be,” cried mac an Dáv joyously.

“Go,” said Mongan, “to Rath Descirt of Bregia; you know that place?”

“As well as my tongue knows my teeth.”

“Duv Laca is there; see her, and ask her what she wants me to do.”

Mac an Dáv went there and returned.

“Duv Laca says that you are to come at once, for the King of Leinster is journeying around his territory, and Kevin Cochlach, the charioteer, is making bitter love to her and wants her to run away with him.”

Mongan set out, and in no great time, for they travelled day and night, they came to Bregia, and gained admittance to the fortress, but just as he got in he had to go out again, for the King of Leinster had been warned of Mongan's journey, and came back to his fortress in the nick of time.

When the men of Ulster saw the condition into which Mongan fell they were in great distress, and they all got sick through compassion for their king. The nobles suggested to him that they should march against Leinster and kill that king and bring back Duv Laca, but Mongan would not consent to this plan.

“For,” said he, “the thing I lost through my own folly I shall get back through my own craft.”

And when he said that his spirits revived, and he called for mac an Dáv.

“You know, my friend,” said Mongan, “that I can't get Duv Laca back unless the King of Leinster asks me to take her back, for a bargain is a bargain.”

“That will happen when pigs fly,” said mac an Dáv, “and,” said he, “I did not make any bargain with any king that is in the world.”

“I heard you say that before,” said Mongan.

“I will say it till Doom,” cried his servant, “for my wife has gone away with that pestilent king, and he has got the double of your bad bargain.”

Mongan and his servant then set out for Leinster.

When they neared that country they found a great crowd going on the road with them, and they learned that the king was giving a feast in honour of his marriage to Duv Laca, for the year of waiting was nearly out, and the king had sworn he would delay no longer.

They went on, therefore, but in low spirits, and at last they saw the walls of the king's castle towering before them. and a noble company going to and fro on the lawn.

Chapter 19

T

hey sat in a place where they could watch the castle and compose themselves after their journey.

“How are we going to get into the castle?” asked mac an Dáv.

For there were hatchetmen on guard in the big gateway, and there were spearmen at short intervals around the walls, and men to throw hot porridge off the roof were standing in the right places.

“If we cannot get in by hook, we will get in by crook,” said Mongan.

“They are both good ways,” said mac an Dáv, “and whichever of them you decide on I'll stick by.”

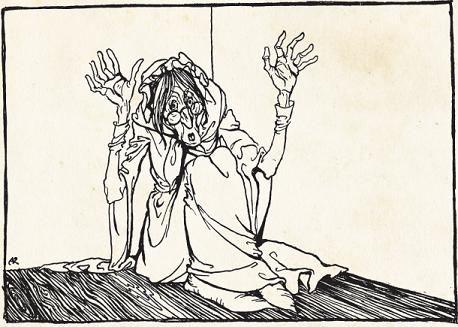

Just then they saw the Hag of the Mill coming out of the mill which was down the road a little.

Now the Hag of the Mill was a bony, thin pole of a hag with odd feet. That is, she had one foot that was too big for her, so that when she lifted it up it pulled her over; and she had one foot that was too small for her, so that when she lifted it up she didn't know what to do with it. She was so long that you thought you would never see the end of her, and she was so thin that you thought you didn't see her at all. One of her eyes was set where her nose should be and there was an ear in its place, and her nose itself was hanging out of her chin, and she had whiskers round it. She was dressed in a red rag that was really a hole with a fringe on it, and she was singing “Oh, hush thee, my one love” to a cat that was yelping on her shoulder.