Jacquards' Web (14 page)

Authors: James Essinger

Another inspired aspect of Babbage’s punched-card system was that it provided a

permanent

record of the machine’s read-out. Furthermore, if the operator was certain that the correct series of punched cards had been installed in the machine at the start of the calculation, the operator could be confident that the

entire calculation

would be done without error.

Babbage also developed his own methods for reducing the number of operations needed to perform a particular calculation.

Some of these are so complex that even today they are not fully understood. In addition, he designed systems by which his Engines would be self-correcting in the event that anything went wrong with them. In particular, his plans included measures that would render the machine unable to act on instructions from, say, a card that had inadvertently slipped out of place. These techniques used a system of locking devices that immobilized certain wheels during a calculating cycle, so that they would not be at risk of accidental movement. Babbage also designed 92

The Analytical Engine

mechanisms to ensure that a wheel could only be moved by an input from a legitimate source. He stated specifically in his plans that when the machine was working properly, it would be impossible for an operator to take any action that would produce false results.

As Babbage applied and extended Jacquard’s ideas, he developed a passion for finding out all he could about the life and work of the French inventor. The first and most important consequence of this was the letter, already quoted, which he wrote in December

1839

to his friend Jean Arago asking the Frenchman to obtain two woven portraits of Jacquard if they were commercially available, or at least one if they were not. In the same letter, as we have seen, he also begged Arago to send him any ‘memoir’ that might shed some light on Jacquard’s life.

A few weeks later, on

24

January

1840

, Babbage received a reply in French. Arago wrote:

My dear friend and colleague

I fear that the person from Lyons of whom I have made enquiries for information about the Jacquard portrait must be out of town. I haven’t had any answer to my queries … Please be assured that I will completely fulfil,

con amore

, the commission with which you have charged me. I do not want you to have the slightest reason to doubt the high esteem in which I hold your talents and your character, nor the importance I attach to our friendship.

Your devoted friend Jean Arago.

Arago was as good as his word. He stuck to the task, and by the spring appears to have been successful in obtaining at least one of the woven portraits that Babbage longed to own.

Driven on by curiosity and admiration, Babbage made a personal pilgrimage to Lyons later that year to see Jacquard’s 93

Jacquard’s Web

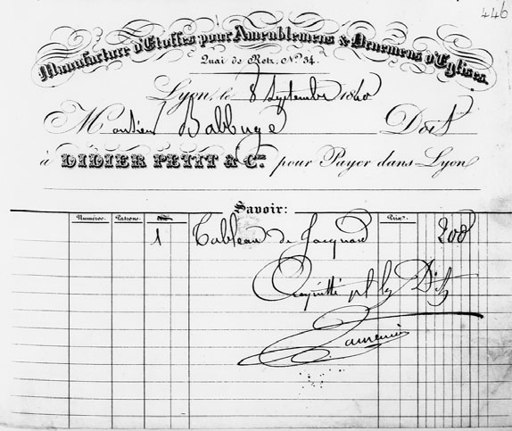

Babbage’s own invoice for the portrait he so much desired. This clearly shows the sum he paid— 200 francs.

loom in action. His visit to Lyons is yet further evidence of how intimately he felt his own work to be related to Jacquard’s.

The story of Babbage’s visit to Lyons contains some intriguing surprises. Buried in the Babbage papers at the British Museum there is an invoice, dated

8

September

1840

, issued by the French Society for the Manufacture of Fabrics for the Furnishing and Decoration of Churches. This relates to the purchase of a ‘tableau’ (that is, the woven portrait) of Jacquard produced by the Lyons firm of Didier Petit & Co. The invoice is made out to ‘Monsieur Babbage’. It seems quite clear that Babbage kept the invoice as a record of having purchased the woven portrait and of how much it cost him.

The firm of Didier Petit & Co no longer exists. The official 94

The Analytical Engine

guidebook for Lyons of

1835

reveals the company to have been a manufacturer of rich fabrics used in furnishing and church decoration. The address is given as

34

Quai de Retz. This is now known as Quai Jean Moulin (after the heroic World War II Resistance leader) and is located on the east side of La Presqu’île, just south of Croix Rousse. The invoice is for

200

francs. The daily average wage of an artisan in

1840

was about four francs.

Comparing wage rates today with

1840

, we can conclude that Babbage paid about £

2500

(about $

4000

) at modern prices for his woven portrait of Jacquard—the clearest indication of how badly he wanted it.

It is natural to assume that the invoice in Babbage’s papers relates to the woven portrait of Jacquard that Babbage obtained through Arago, and which he put on show at his soirées. But in fact this was not the case. Instead, the invoice turns out to be for a

second

portrait of Jacquard that Babbage obtained under rather more exotic circumstances.

In June or July

1840

, Babbage had been invited by the Italian mathematician Giovanni Plana to attend a meeting of Italian scientists scheduled to take place in September in Turin, then the capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Babbage was invited to a similar meeting the previous year but had declined, pleading that he was too busy with his work on the Analytical Engine. This time he accepted. Very likely he did so because of the extraordinary insight into the importance of the Analytical Engine shown by Plana in his letter of invitation.

In his autobiography, Babbage recalled:

In

1840

I received from my friend M. Plana a letter pressing me strongly to visit Turin at the then approaching meeting of Italian philosophers. M. Plana stated that he had enquired anxiously of many of my countrymen about the power and mechanism of the Analytical Engine. He remarked that from all the information he could collect the case seemed to stand thus: ‘Hitherto the

legislative

department of our analysis has 95

Jacquard’s Web

been all-powerful—the

executive

all feeble. Your engine seems to give us the same control over the executive which we have hitherto only possessed over the legislative department.’

Considering the exceedingly limited information which could have reached my friend respecting the Analytical Engine, I was equally surprised and delighted at this exact prevision of its powers.

Plana’s comment in effect amounted to a recognition that the Analytical Engine might be able to solve the long-standing problem of the lack of processing power to evaluate complex mathematical formulae. It was an extraordinarily far-sighted observation, and it is hardly surprising that Babbage was so thrilled at Plana’s perceptiveness.

The German Romantic poet and philosopher Novalis once remarked: ‘It is certain my conviction gains infinitely, the moment another soul will believe in it.’ This could be a motto for all of Babbage’s life; it explains much of his behaviour, especially during the long and often lonely years when he was labour-ing on his cogwheel computers. With no efficient working version of a Difference Engine or Analytical Engine to show the world, he was obliged to seek what seemed the next-best thing; the society of those who appeared to understand what he was trying to do. The fact that he was prepared to travel all the way to Italy—a far from easy journey in

1840

, even for a man of Babbage’s financial resources and energy—suggests how cut off from empathy and support at home he perceived himself to be.

Very possibly he was also influenced in his decision to make the journey by the fact that the journey to Turin offered an ideal opportunity to visit Lyons on the way, and find out more about Joseph-Marie Jacquard. The Lyons silk industry had sprung up there partly because of the city’s proximity to Italy, and now Babbage was exploiting that very fact to combine his excursion to Turin with a visit to Lyons.

96

The Analytical Engine

Babbage left England for Paris in the middle of August

1840

.

In the capital, he collected letters of introduction from Arago and other friends to people in Lyons.

Towards the end of August he arrived in Jacquard’s birth-place. As he relates in

Passages

:

On my road to Turin I had passed a few days at Lyons, in order to examine the silk manufacture. I was especially anxious to see the loom in which that admirable specimen of fine art, the portrait of Jacquard, was woven. I passed many hours in watching its progress:

What Babbage says here is ambiguous. Does he mean that he spent the ‘many hours’ just watching a Jacquard loom operating, or that he actually watched the loom weaving a

24 000

-card Jacquard portrait? There is the tantalizing implication that the latter is the case.

If he had watched the portrait being woven, it would indeed have been an undertaking requiring ‘many hours’. Assuming that the weaver was working at the usual Jacquard loom speed of about forty-eight picks per minute (say,

2800

per hour), the entire weaving process for the

24 000

picks would have taken more than eight hours per portrait, excluding breaks at the local

bouchon

. When Babbage was immersed in an intellectual pursuit, the intensity of his concentration was beyond compare. Whether he did in fact watch a Jacquard portrait being woven, is it not at least perfectly possible to

imagine

him observing the creation of the woven portrait of his hero from the very first pick of the shuttle to the very last?

And what about the invoice? The truth is that this relates not to the Jacquard portrait Arago procured for Babbage, but rather to a

second

woven portrait that Babbage obtained while in Lyons.

This portrait, which he quite possibly witnessed being made, he did not keep for himself. Instead, later in his travels he made a present of it, in Turin, to the Queen of Piedmont and Sardinia, whose brother the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Leopold II, had 97

Jacquard’s Web

extended friendship and hospitality to Babbage twelve years earlier, when Babbage visited Italy on the European tour he made to console himself after his wife Georgiana’s death.

98

A question of faith and funding

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ❚ 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ❚ 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ❚ 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 ❚ 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 ❚ 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 ❚ 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5

6 6 6 6 6 6 ❚ 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6

7 7 7 ❚ 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7

8 8 8 8 ❚ ❚ 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8

9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 ❚ 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ❚ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

In public Babbage kept up a bold front but his private letters tell a different story. He had little hope of an Analytical Engine being built in his lifetime. The government of the Duke of Wellington and the reform government had come and gone, and with them all hope of securing the necessary support for such a project in nineteenth century Britain. With no expectation of public support or backing, the courage and determination with which he pursued the work in the face of enormous difficulties is very impressive.

Anthony Hyman,

Charles Babbage, Pioneer of the Computer

,

1982

When we think of Babbage leaving for Turin to discuss the Analytical Engine with Giovanni Plana and other leading Italian scientists in the summer of

1840

, and meeting royalty, it is easy to romanticize the situation and assume Babbage was at the pinnacle of his achievements.

But this was not the case at all. The truth is that when Babbage left for Italy, his career at home was in shreds. Yes, 99

Jacquard’s Web

among some of Europe’s greatest minds, Babbage could look forward to receiving the respect and understanding he longed for. Back in Britain, though, negotiations with the Government over the provision of funding to continue his work had foundered.

This was to a large extent because Babbage was finding it increasingly difficult to get taken seriously in his native land. He was a genius, but diplomacy was not his strong point. Back in

1834

he had made the fatal, and really rather stupid, mistake of telling the British Government he had abandoned work on the Difference Engine because he had invented another machine which ‘superseded’ it. The other machine was, of course, the Analytical Engine.

Why did Babbage inform the Government he had abandoned work on the very machine the Government had supported with such lavish financial grants? The confession did not even turn out to be strictly true: he never entirely abandoned his labours on the Difference Engine and was still conducting useful work on it in the

1850

s. But Babbage was obsessively honest and throughout his life motivated by a sense of justice so pronounced that it often placed his own interests in jeopardy. He felt it was, in effect, only fair to mention the new direction his work was taking. Another likely factor was that he was proud of his new idea and keen to tell people about it.