Jessen & Richter (Eds.) (66 page)

Read Jessen & Richter (Eds.) Online

Authors: Voting for Hitler,Stalin; Elections Under 20th Century Dictatorships (2011)

E L E C T I O N S , P L E B I S C I T A R Y E L E C T I O N S , A N D P L E B I S C I T E S

253

Kershaw, Ian (1991).

Hitler

. London: Longman.

— (2001).

The “Hitler Myth”. Image and Reality in the Third Reich

. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Klemperer, Victor (2000).

Testimoniare fino all’ultimo. Diari 1933–1945

. Eds. Anna Ruchat and Paolo Quadrelli. Milan: Mondadori.

Kotze, Hildegard von, and Helmut Krausnick (1966).

“Es spricht der Führer”. 7 exem-plarische Hitler-Reden

. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann.

Leonetti, Alfonso [Saraceno, Guido] (1929).

“No”. Come si è votato il 24 marzo in

Italia. (Fatti e documenti sul Plebiscito fascista)

. Paris: Edizioni italiane di coltura sociale.

Maraviglia, Maurizio (1929). Dopo il plebiscito. In

Momenti di vita italiana

, 236–41.

Rome: Pinciana.

Minuth, Karl-Heinz (ed.). (1983).

Akten der Reichskanzlei. Regierung Hitler 1933–1938

.

Vols. I/1, I/2. Boppard am Rhein: Boldt.

Mussolini, Benito (1923). Forza e consenso.

Gerarchia

, 2, 802–03.

— (1957). La diana del nuovo tempo. In

Opera omnia

. Vol. XXIII, 267–73.

Florence: La Fenice.

Omland, Frank (2006).

“Du wählst mi nich Hitler!”. Reichstagwahlen und Volksabstimmungen in Schleswig-Holstein 1933–1938

. Hamburg: Books on demand.

Pavone, Claudio (1996). Appunti sul principio plebiscitario. In Giuseppe Carbone (ed.).

La virtù del politico

, 151–81. Venice: Marsilio.

Poetzsch-Heffter, Fritz, Carl-Hermann Ule, and Carl Dernedde (1935). Vom Deut-

schen Staatsleben (30. Januar bis 31. Dezember 1933).

Jahrbuch des öffentlichen

Rechts

, 22, 1–272.

Pombeni, Paolo (1997). Typologie des populismes en Europe (19e–20e siècles).

Vingtième siècle

, 56, 48–76.

Rapone, Leonardo (2010). Un plebiscitarismo riluttante. I plebisciti nella cultura politica e nella prassi del fascismo italiano. In Enzo Fimiani (ed.).

Vox populi?

Pratiche plebiscitarie in Francia, Italia, Germania (secoli XVIII–XX)

, 145–77.

Bologna: Clueb.

Rocco, Alfredo (1928).

Atti Parlamentari, Camera dei Deputati, Documenti parlamentari,

XXVII Legislatura, sessione 1924–1928, Disegni di Legge-Relazioni, Relazione Alfredo

Rocco

, 27 febbraio.

Santomassimo, Gianpasquale (ed.). (2003).

La notte della democrazia italiana. Dal

regime fascista al governo Berlusconi

. Milan: il Saggiatore.

Schmitt, Carl (1935). Stato, movimento, popolo. Le tre membra dell

’

unità politica.

In Delio Cantimori (ed.).

Principii politici del nazionalsocialismo. Scritti scelti

, 173–

231. Florence: Sansoni.

Silva, Umberto (1973).

Ideologia e arte del fascismo

. Milan: Mazzotta.

Ungari, Paolo (1963).

Alfredo Rocco e l’ideologia giuridica del fascismo

. Brescia: Morcel-liana.

“Germany Totally National Socialist”—

National Socialist

Reichstag

Elections and

Plebiscites, 1933–1938: The Example of

Schleswig-Holstein

Frank Omland

On November 12, 1933, the first two ballots of the Nazi dictatorship were

held. Voters were asked both to elect a new National Socialist single-party

parliament and to approve Germany’s withdrawal from the League of

Nations. On the following day, the

Kieler Zeitung

, a pro-Nazi newspaper, ran the headline: “The miracle of November 12. Germany totally National

Socialist”. And its chief editor and Party member, Max Gröters, com-

mented:

A miracle really has happened. The millions who voted yesterday in what was a

record turnout—a turnout, indeed, unprecedented in German history—made this

miracle possible: Marxism and Bolshevism have disappeared from Germany. The

forces of evil that brought about Germany’s downfall have been destroyed; and it was the sheer force of National Socialism in both principle and practice that dealt them their death blow. It is only when we bear in mind that yesterday’s ballot was secret, and that every single German citizen could vote as he wished, that the true scale of the miracle becomes clear; it is the miracle of unanimous faith in the aims and politics of Adolf Hitler [...] Germany has become a single-party state, an

organism constructed and led according to wholly National Socialist principles.1

This comment was not mere propaganda. Although the results of the first

two ballots in the single-party state may not have been a “miracle” in the

strict sense, the fact that nearly 90 per cent of those entitled to vote had

registered their support for the Party took the National Socialists by sur-

prise. What made the result even more credible to those in power and to

their supporters was that the ballot had supposedly been secret—some-

thing that did not fail to impress their opponents, too. Although not all of

——————

1

Kieler Zeitung

, November 13, 1933. “The miracle of 12 November: Germany totally National Socialist”.

“ G E R M A N Y T O T A L L Y N A T I O N A L S O C I A L I S T ”

255

Germany had become “totally National Socialist”, what was apparent to

both sides was that the regime’s opponents had been marginalized.

Many of the questions concerning ballots in dictatorships are raised by

this episode: What do people do when they have to vote in a dictatorship?

Why and for what purpose does a regime stage elections, when it does not

wish to give people a choice? How are the results of such ballots inter-

preted by those in power and by the persecuted opposition? And can we

draw conclusions on the nature of society in a dictatorship from what

happened in the elections and from the election results?.

Possible answers to these questions can be found in numerous sources:

election statistics, NSDAP reports, administrative files, files belonging to

the apparatus of persecution, and documents from the illegal workers’

movement (Omland 2006a, 13–15, 243–44).2 These sources enable us to

reconstruct the election campaigns and to show what room for maneuver

those entitled to vote really had. Moreover, by analyzing the election re-

sults, we can make judgments concerning the extent to which National

Socialism was embedded within the population as a whole. When brought

together, these sources enable us to answer the question: Who voted where

and how against or for the Nazi regime, and which conditions encouraged

or discouraged voting behavior either way?

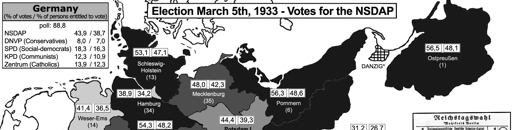

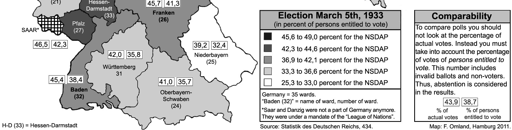

My focus is on the region of Schleswig-Holstein, which had already

been an early NSDAP stronghold during the Weimar Republic. From 1928

onwards, this Prussian province in Northern Germany was one of the

most important regions in the Party’s ascent, which can be seen not only in

the Party’s growing membership, but also in their election successes. Be-

tween 1928 and 1933, the Party generally won over 10 per cent more of the

votes in Schleswig-Holstein than in the other regions of Prussia and the

German

Reich

.3 It was only in the

Reichstag

election of March 5, 1933 (47.1

per cent in Schleswig-Holstein compared to 38.7 per cent as a national

average) that Schleswig-Holstein was toppled from its position of

ascendancy by five other constituencies, but it nonetheless remained a

stronghold for the Party.4 What is all the more remarkable, then, is that, in

——————

2 For literature and statistics, see also my database of election statistics at www.akens.-

org/akens/texte/diverses/wahldaten/index.html (accessed on January 2, 2011).

3 Percentage according to number of those entitled to vote rather than according to number of valid votes cast. Distortions due to electoral participation are thereby avoided.

4

Reichstag

election September 14, 1930: 22.1 per cent (German

Reich

14.9 per cent);

Landtag

election April 24, 1932: 43.3 per cent (Prussia: 29.6 per cent);

Reichstag

election