John Quincy Adams (45 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

When the clerk read the next resolution and called his nameâhis was third on the alphabetical rollâhe tried to stand, his right hand gripping

his desk as he rose. Then he slumped to his leftâfortunately, into the arms of a fellow congressman who had been watching him.

his desk as he rose. Then he slumped to his leftâfortunately, into the arms of a fellow congressman who had been watching him.

Â

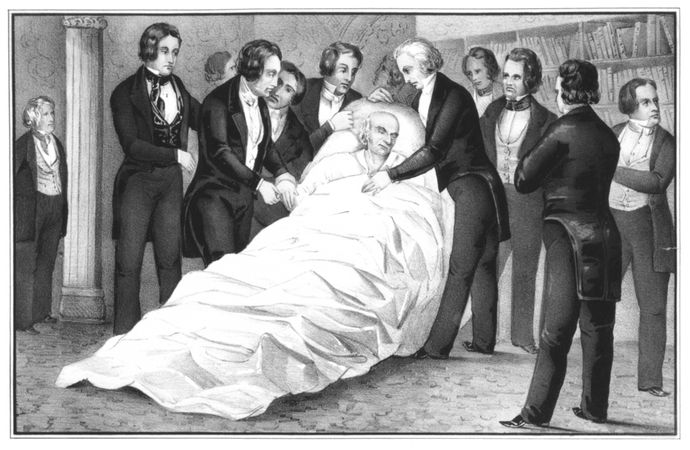

The death of John Quincy Adams in the Capitol he loved, with, presumably, his former secretary of state Henry Clay holding his right hand.

(FROM A NATHANIEL CURRIER LITHOGRAPH, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(FROM A NATHANIEL CURRIER LITHOGRAPH, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

“Mr. Adams is dying,” cried a congressman nearby. “Mr. Adams is dying.” The words passed from member to member. Other members found a couch that they brought onto the House floor and helped their stricken colleague stretch out. Someone thought to ask for a formal adjournment. Both the Senate and Supreme Court followed suit when they learned of John Quincy's collapse. A group of congressmen carried the sofa and its occupant into the rotunda to give John Quincy more air, but they eventually moved it into the Speaker's office, where they barred every one but physicians, family, and close friends. John Quincy revived enough to thank those around him and to ask for Henry Clay, who arrived weeping. He clasped his old President's hand, unable to say a word before he finally left, inconsolable.

“This is the end of earth, but I am composed,” John Quincy whispered, then lapsed into a coma. Louisa arrived with a friend and looked down at her husband, but his eyes showed no sign of consciousness. Eighty-year-old John Quincy lay in a coma for the next two days, and at 7:20 p.m., on February 23, 1848, he died in the Capitol he adored.

The next day, House members appointed a committee with one member from each state to escort John Quincy home to Massachusetts for burial. In the Senate, one of his bitter political foes, Thomas Hart Benton, stood to proclaim, “Whenever his presence could give aid and countenance to what was useful and honorable to man, there he was. . . . Where could death have found him but at the post of duty?”

41

41

The nation mourned as it had not since the deaths of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. John Quincy lay in state in a committee room in Congress for two days after his death; thousands filed by silently, often not knowing why exactly, but somehow realizing they had lost a champion of their rightsâa representative of no single constituency, state, or region but of all Americans and of the whole nation. He was an aristocrat of an earlier generation, raised in an age of deference, who spoke a rich language that ordinary people could seldom fathom, but in the end, they sensed that he spoke for their greater good and to protect their rights and freedoms.

A single cannon blast awakened Washington on Saturday morning, February 25; another boom shook the city a minute later and every minute until noon. Again, the multitude reappeared, filling the streets like a great river flowing to the Capitol. At 11:50, the bell on Capitol Hill began to toll, and the President of the United States led the justices of the Supreme Court, high-ranking members of the military, the diplomatic corps, and members of the Senate into the House chamber. John Quincy lay in a silver-framed coffin on an elevated platform in front of the rostrum, his eloquence still resounding in the silent chamber:

My cause is the cause of my country and of human liberty . . . the fulfillment of prophesies that the day shall come when slavery and war shall be banished from the face of the earth.

42

42

With the President seated at the Speaker's right, the vice president at his left, and the portraits of Washington and Lafayette looking down on them all, the chaplain of the House prayed and set off what Charles Francis Adams called “as great a pageant as was ever conducted in the United States.” Choirs sang to the gods, and orators lifted their voices to men, repeating the appeal for John Quincy's precious “Union.” When the assembly had intoned its final hymn, pallbearers carried the former President out of the Capitol to a silent multitude that stretched to the edge of the city. The great casket emerged from the Capitol, surrounded by an official committee of escort and followed by Charles Francis Adams and his wife, then John Quincy's closest friends from the legislature. In the procession that followed, the Speaker of the House led members of that body, the Senate, then President Polk, justices of the Supreme Court, the diplomatic corps, and an interminable line of military officials, state officials, college students, firemen, and members of craftsmen's organizations and literary societies. . . . It was endlessâa collective outpouring of love and veneration the nation had rarely seen.

John Quincy lay in rest at the Congressional Cemetery for a week before the congressional committee of escortâa member from each stateâcame to take him aboard a train to Boston. Thousands lined the tracks northward to bow their heads as the train passed slowly, one car draped in black bearing John Quincy's coffin. The train stopped at various stations and crossings to allow citizens to climb aboard and say their good-byes as they filed past him. Churches sang his praises; newspapers expounded his glory and cited and published his oratory and poetry. Thousands awaited his arrival in Boston, filling the streets and all but blocking passage for his coffin to Faneuil Hall for a massive funeral ceremony before members of the state legislature and other prominent citizens. With the end of the eulogy and last prayer, the congressional committee delivered the body of their colleague, John Quincy Adams, to Mayor Josiah Quincy, John Quincy's cousin and former president of Harvard, for transport to the family vault in Quincy. A lifetime of friends and neighbors had gathered with his relatives and family to place John Quincy beside his father. As

they laid John Quincy to rest, a small troop fired rifles in a last salute from nearby Penn's Hill, where John Quincy and his mother, Abigail, had watched the Battle of Bunker's Hill and the beginning of the Revolution that spawned a new nation.

they laid John Quincy to rest, a small troop fired rifles in a last salute from nearby Penn's Hill, where John Quincy and his mother, Abigail, had watched the Battle of Bunker's Hill and the beginning of the Revolution that spawned a new nation.

Day of my father's birth, I hail thee yet.

What though his body moulders in the grave,

Yet shall not Death th' immortal soul enslave;

The sun is not extinctâhis orb has set.

And Where on earth's wide ball shall man be met,

While time shall run, but from thy spirit brave

Shall learn to grasp the boom his Maker gave,

And spurn the terror of a tyrant's threat?

Who but shall learn that freedom is the prize

Man still is bound to rescue or maintain;

That nature's God commands the slave to rise,

And on the oppressor's head to break his chain.

Roll, years of promise, rapidly roll round,

Till not a slave shall on this earth be found.

What though his body moulders in the grave,

Yet shall not Death th' immortal soul enslave;

The sun is not extinctâhis orb has set.

And Where on earth's wide ball shall man be met,

While time shall run, but from thy spirit brave

Shall learn to grasp the boom his Maker gave,

And spurn the terror of a tyrant's threat?

Who but shall learn that freedom is the prize

Man still is bound to rescue or maintain;

That nature's God commands the slave to rise,

And on the oppressor's head to break his chain.

Roll, years of promise, rapidly roll round,

Till not a slave shall on this earth be found.

A little more than twelve years after John Quincy diedâon December 24, 1860âSouth Carolina's legislature proclaimed without dissent that “the union now subsisting between South Carolina and the other States, under the name of the âUnited States of America,' is hereby dissolved.” Early in 1861, ten other states followed suit, and in April 1861, the civil war that John Quincy Adams had predicted was under way, eventually costing the lives of more than 275,000 Americans.

Louisa Adams died four years after John Quincy, on May 15, 1852, in Washington, DC.

She and her husband now lie together next to John and Abigail Adams in a granite crypt in the church in Quincy, Massachusetts, where Charles Francis had them all transferred after escorting his mother's body from the capital. Although no subsequent members of the Adams family ever followed John or John Quincy Adams to the presidency, no American family ever surpassed the Adamses in accession to national prominence in so many fields. Beginning with his son Charles Francis Adams, who served as American ambassador to Britain and twice ran unsuccessfully for vice president, John Quincy Adams spawned an august line of American scholars, teachers, historians, authors, legislators, jurists, diplomats, lawyers, doctors, business leaders, and other professionals who upheldâand upholdâthe principle of their distinguished ancestor:

You must have one great purpose of existence . . . to make your talents and your knowledge most beneficial to your country and most useful to mankind.

âJOHN QUINCY ADAMS, “TO MY CHILDREN.”

44

44

Notes

Explanatory note: John Quincy Adams kept his diary from November 1779 to December 1847, accumulating a total of 14,000 pages. The early diaries, from November 1779 to December 1788, were published in book form as

Diary of John Quincy Adams

(Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1981). The rest of the diaryâfifty-one volumes in allâis only available digitally, over the Internet, by logging on to “The Diaries of John Quincy Adams: A Digital Collection,” on the website of the Massachusetts Historical Society (

www.masshist.org/jqadiaries

). In this book, notes referring to extracts from the first two published volumes of the diary will show the appropriate volume and page numbers. When extracted from the Internet, the notes will simply show the appropriate date and the initials MHS (Massachusetts Historical Society).

Diary of John Quincy Adams

(Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1981). The rest of the diaryâfifty-one volumes in allâis only available digitally, over the Internet, by logging on to “The Diaries of John Quincy Adams: A Digital Collection,” on the website of the Massachusetts Historical Society (

www.masshist.org/jqadiaries

). In this book, notes referring to extracts from the first two published volumes of the diary will show the appropriate volume and page numbers. When extracted from the Internet, the notes will simply show the appropriate date and the initials MHS (Massachusetts Historical Society).

Â

Abbreviations

:

:

| AA | Abigail Adams |

| AP | Adams Papers |

| AFC | Adams Family Correspondence |

| JA | John Adams |

| JM | James Monroe |

| JQA | John Quincy Adams |

| LCA | Louisa Catherine Adams |

| MHS | Massachusetts Historical Society |

1

Charles Francis Adams, ed.,

Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848

, 12 vols. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1874), 7:164 (hereafter

Memoirs

). Mistakenly published in his

Memoirs

as written on October 30, 1826. In his old age, JQA had slipped the undated poem at random between pages of his diary bearing the 1826 date, and his son, Charles Francis, in compiling his father's

Memoirs

for publication, assumed that was the date on which his father had written it.

CHAPTER 1Charles Francis Adams, ed.,

Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848

, 12 vols. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1874), 7:164 (hereafter

Memoirs

). Mistakenly published in his

Memoirs

as written on October 30, 1826. In his old age, JQA had slipped the undated poem at random between pages of his diary bearing the 1826 date, and his son, Charles Francis, in compiling his father's

Memoirs

for publication, assumed that was the date on which his father had written it.

1

L. H. Butterfield, ed.,

The Adams Papers: Diary and Autobiography of John Adams

, 4 vols. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961), 4:6â7.

L. H. Butterfield, ed.,

The Adams Papers: Diary and Autobiography of John Adams

, 4 vols. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961), 4:6â7.

2

Ibid.

Ibid.

3

Ibid., 12.

Ibid., 12.

4

Ibid.

Ibid.

6

Increase Mather, in Samuel Eliot Morison,

Three Centuries of Harvard

,

1636â1936

(Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1936), 35.

Increase Mather, in Samuel Eliot Morison,

Three Centuries of Harvard

,

1636â1936

(Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1936), 35.

Other books

GHOST GAL: The Wild Hunt by Nash, Bobby

Haunted Renovation Mystery 1 - Flip That Haunted House by Rose Pressey

The Capture by Tom Isbell

The No Cry Nap Solution by Elizabeth Pantley

Stone (The Forbidden Love Series Book 1) by Angel Rose

Spirit's Release by Tea Trelawny

Soulprint by Megan Miranda

The Bad Nurse by Sheila Johnson

The Chaos Weapon by Colin Kapp

Retaliation: An Alpha Billionaire Romance by Landish,Lauren