Kerry Girls (13 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

By early 1850 hostility to the entire scheme had built up in Australia. Due to the negative reactions coming from upper- and middle-class opinion and echoed in the national newspapers, the scheme was brought to an end in that year. There were a number of elements involved. There was an inherent anti-Irish, anti-Catholic and anti-female prejudice in the colonies at that time. The orphans were denounced as ‘immoral, useless and untrained domestic servants, a drain upon the public purse, a financial liability, who, being blindly devoted to their religion, threatened to bring about a Popish ascendancy in New South Wales and Victoria’.

41

In December 1849 the Orphan Emigration Committee in Australia stated that 200 of the orphans were unemployed and this was mainly due to their inability to perform housework, rather than the earlier charges of immorality.

42

Added to the general objections as to their suitability was a particular prejudice towards Irish Catholic immigrants, promulgated in the main by Scottish and Northern Irish Presbyterians who had settled in New South Wales from 1840 onwards. Some of these were small landholders who sold their tenant rights and set out to seek a better life in the new colony. They had bought into the new lands available to them, were hard workers and were nervous that they would be out numbered now by Catholics. Their chief spokesman, John Dunmore Lang, then a Member of the legislative council of the colony, wrote to Earl Grey urging the emigration only of ‘virtuous and industrious Protestants’.

43

Margaret Cronin

Margaret Mary Cronin was the third child of Myles Cronin and Honora Clifford (‘Cluvane’ on her Baptismal Certificate), who were married on 10 February 1820 at Dunkerron in County Kerry.

Margaret was born in 1831, which meant she was 19 years of age when she emigrated, but on arrival her age was recorded as 16. The other children of Myles and Honora were John born 1821, Mary born 1824, Myles born 1837 and Cornelius born 1840. The baptism certificate of Margaret records the following:

Name MARGARET CRONIN | |||

Date of Birth 4 July 1831 [BASED ON OTHER DATE INFORMATION] | |||

Address DUNKERRON | |||

Father MYLES CRONIN | Mother HANORA CLUVANE | ||

Father Occupation NR | Priest REV: R.F.M. | ||

Sponsor 1 DERMOT SULLIVAN | Sponsor 2 MARY SIGERSON | ||

Book | Number | Page | Entry Number Record_Identifier |

1 | N/R | 165 | KY-RC-BA-267000 |

In the Tithe Applotment Books

44

of 1840, Myles Cronin’s rent in the townland of Dunkerron, Parish of Templenoe in the Diocese of Ardfert and Aghadoe is £5 10

s

0

d

. By the time of Griffith’s Valuation (1848–1851) Myles Cronin’s family is no longer a tenant on this land. We would have to presume that both parents had died in the Famine prior to Margaret’s selection in Kenmare Workhouse in December 1849.

Margaret arrived on the

John Knox

at Port Jackson on 29 April 1850. Her arrival documentation also states that her parents were ‘both dead’, she could not read or write and had no relatives in the colony. We have no record of where she was initially apprenticed, but it would appear that she stayed in Sydney and was not moved on to Moreton Bay as a number of the other Kenmare girls were.

Margaret’s great-great-grandson Peter Booth tells us that:

Margaret Mary Cronin arrived in Sydney on 29th April 1850 along with over 250 other Irish Orphan girls aboard

John Knox

after a voyage of nearly five months. She would have been assigned as a servant to a family in Sydney.

On 8th January 1856, Margaret Cronin married John William Clark, a carpenter and free settler, who had arrived from Plymouth some three years earlier. They had ten children in various parts of New South Wales including George 1857, Ellen 1858, Ernest 1861, Margaret 1863, Agnes 1865, Kate 1866, Emily 1868, Minnie 1869, John 1872, before Margaret died with her last child in 1873. She is buried at Bathurst, New South Wales.

Descendants include a Deputy Commissioner of Railways, a local mayor and a Prime Minister’s secretary. Margaret Cronin has significantly contributed to the fabric of Australia.

In Listowel, the Board of Guardians were apparently unaware of the situation building up in Australia. On 7 March 1850 an excerpt from the Minutes of their meeting reads:

Resolve that we deem it a matter of incalculable advantage to the Union, to promote by every means, the emigration of the paupers, who are now crowding the Workhouse, not only as a means of providing for the most deserving of those persons, but as to the ultimate relief to the Union and as Lieutenant Henry has selected from among the female orphans of this house, 20 named underneath whom he considers eligible for emigration to Australia, we hereby consent to provide them with necessary outfit as decided upon by the Emigration Commissioners and to defray their expenses to the port of Embarkation … and the Matron hereby directed to provide the necessary outfits for the following girls.

45

Mary Courtney | Catherine O’Sullivan | Anne Buckley | Julia Daily |

Ellen Leary | Bridget Griffin | Mary Griffin | Margaret Ginniew |

Mary Daly | Johanna Scanlon | Deborah Kissane | Catherine Mullowney |

Mary Sullivan | Mary Stack | Honora Brien | Mary Creagh |

Catherine Connor | Johanna Sullivan | Margaret Connor | Ellen Relihan |

Minutes of Listowel Board of Guardians, 7 March 1850

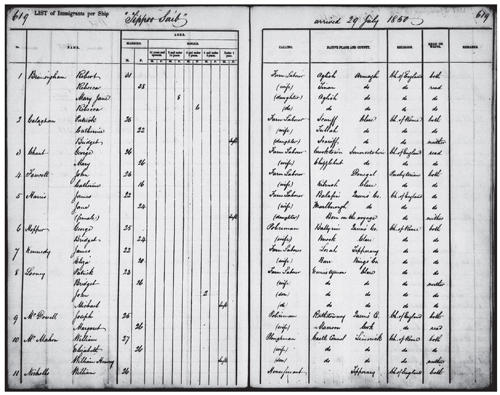

Again the same system of selection and medical checks were carried out. On 8 April 1850 they sailed from Plymouth on the

Tippoo Saib

, an ageing barque of 1,022 tons. The master was Captain W. Morphew. There were 297 orphans in total on board.

Four months later, following brief stops for supplies and water in Tenerife and Capetown, the

Tippoo Saib

was escorted into Sydney Cove on 29 July 1850. Captain Morphew’s report to the health authorities in Sydney stated that, of his total passengers, ‘one was suffering from lunacy, one had consumption and another hysteria’. Three had died on the voyage from ‘exhaustion, nervous irritation and infection of the brain respectively’.

46

Grave doubts would have to be cast on the selection process, however well-meaning Lieutenant Henry was. Regrettably it would appear that apart from physical appearance, he would have had little choice in matters of the personal attainments of the unfortunate, virtually uneducated girls. The subsequent shipping records show that on arrival a large number of the Kerry orphans were unable to read or write. They were totally untrained in housework, needlework or ‘washing’, though a few may have had the rudiments of farm work. At least three of the orphans were not natives of their Unions. There is no reason to believe that some of the Guardians would not have interfered in the process, thereby promoting the emigration of unwanted orphans from within their own families or communities.

Tippoo Saib

arrivals, 29 July 1850.

The

Tippoo Saib

, with these Listowel girls, was the last of the Earl Grey Scheme ships bringing Irish orphans to the colonies of New South Wales, Moreton Bay, Port Philip and South Australia.

1

Tralee Chronicle

, 7 April 1849, quoted in Kieran Foley, ‘Kerry During the Great Famine’, Unpublished Phd Thesis, UCD 1997, p. 294.

2

Ibid.

3

The Nation

, 26 February 1848, quoted in O’Farrell,

The Irish in Australia 1788 to the Present

(Cork University Press 1966), p. 74.

4

Ibid.

5

Third Report from Select Committee on Poor Laws, p. 157.

6

Letter from Poor Law Commission Office, Dublin sent to the Clerk of each Union entitled Emigration of Orphans from Workhouses in Ireland, 7 March 1848 Appendix (ii).

7

Letter from W. Stanley, Secretary to Poor Law Commissioners, 7 March 1848.

8

Minutes of Board of Guardians Killarney Workhouse Union, 29 April 1848 (held in Kerry Local History Library, Tralee).

9

Ibid., 29 January 1849.

10

Ibid., 13 February 1849.

11

Ibid., 2 May 1849.

12

1849 ‘Shipping Intelligence’

, South Australian Register (

Adelaide, SA: 1839–1900), 12 September, p. 3, viewed 15 October, 2013,

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article50247741.

13

Ibid., 28 March 1849.

14

Ibid., 19 October 1849.

15

‘The method of selection adopted by him was a simple one. As the girls sat in the workhouse refectory he walked amongst them making his choice.’ ‘Irish Orphan Emigration to Australia 1848-1850’ by Joseph A. Robins in

Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review

, Vol. 57, No. 228 (Winter 1968).

16

Minutes of Listowel Board of Guardians, 12 September 1849 (held in Kerry Local History Library, Tralee).

17

Minutes of Board of Guardians Listowel Union Workhouse, 12 September 1849 (held in Local History Section Tralee Library).

18

Ibid., 11 October 1849.

19

Kerry Examiner

, 8 February 1847.

20

Captain Hotham to the Commissioners, 4 January 1848, Poor Law Commissioners,

Papers relating to the relief of distress

, p. 300.

21

Minutes of Board of Guardians Dingle Workhouse 17 March 1849 (held in Kerry Local History Library, Tralee).

22

Ibid., 22 September 1849.

23

Ibid., 15 September 1849.

24

Ibid., 5 October 1849.

25

Ibid., 10 October 1849.

26

London Illustrated News

, October 1849.

27

Minutes of Board of Guardians Eingle Union Workhouse, 6 November 1849 (held in Local History Section, Tralee Library), 70/353.

28

Gray,

Famine Land & Politics

, p. 62-5, quoted in Gerard J. Lyne,

The Landsdowne Estate in Kerry under the agency of William Steuart Trench 1849–72

(Dublin 2001), p. xxxii.

29

Ibid., p. xxxv.

30

Ibid., p. xxxv.

31

Gerard J. Lyne,

Taylors of Dunkerron

, in Journal of KAHS No. 17, 1984, p. 72.

32

Minutes Kenmare Board of Guardians, Wednesday 29

August 1849, p. 82 (held in Kerry Local History Library, Tralee).

33

Ibid., 22 September 1849.

34

Minutes Kenmare Board of Guardians, Wednesday 31 October 1849, p. 186 (held in Kerry Local History Library, Tralee).

35

Ibid., 12 November 1849.

36

Ibid., 17 November 1849.

37

William Steuart Trench

, Realities of Life

(Longmans, London 1869), p. 116.

38

Ibid.

39

Minutes Kenmare Board of Guardians, 29 November 1849.

40

Ibid.

41

Trevor McClaughlin, History Ireland, Accessed online

http://www.historyireland.com/volumes/volume8/issue4/features/?id=245

, 3 January 2013.

42

Christine Kinealy,

This Great Calamity, The Irish Famine 1845–52

(Dublin 1994, 2006), p. 324.

43

Joseph Robins,

The Lost Children:

A Study of Charity Children in Ireland 1700–1900

(Dublin: Institute of Public Administration 1980), p. 208.

44

The Tithe Applotment Books are a vital source for genealogical research for the pre-Famine period/ They were compiled between 1823 and 1837 in order to determine the amount, which occupiers of agricultural holdings over one acre should pay in tithes to the Church of Ireland (the main Protestant church and the church established by the State until its dis-establishment in 1871). There is a manuscript book for almost every civil (Church of Ireland) parish in the country giving the names of occupiers of each townland, the amount of land held and the sums to be paid in tithes.

45

Minutes of Listowel Board of Guardians, 7 March 1850 (Kerry County Library, Tralee).

46

http://www.thenoones.id.au/08_CATH_SHIP/cath_ship.html

.