Kerry Girls (15 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

The Wilson sisters, who were on the Listowel list, also recorded their parents as both dead. The Wilson girls were registered as Church of England and as there are no baptismal certificates for them in the Kerry area, we would have to assume that they were introduced to Listowel Workhouse by one of the Church of England guardians. Margaret Raymond and Julia Daly from Listowel also declared their religion as Church of England.

We know that Margaret Raymond was not initially selected by Lieutenant Henry, but she seems to have been treated as a special case. On arrival in Sydney, she claims to be a cousin of James Raymond, Postmaster General of Australia. Indeed the records bear out this claim as the truth. Margaret states that her parents were William and Hanora (both dead). There is no Church of England or Catholic baptismal record extant for Margaret but a William Raymond and Honora Barrie are registered as the parents of a William Raymond in the Catholic Parish Church Listowel on 12 February 1828, and it is possible that this is Margaret’s brother. This William Raymond was later married to Anne Reeves and had further children baptised as Anglicans in Listowel. William Raymond’s first cousin, James Raymond, had married and taken up residence in County Limerick but suffered some land troubles. Raymond seems to have had access to some of the most prominent names in the New South Wales colony in the nineteenth century and July 1824 Henry Gouldburn wrote on his behalf to Earl Bathurst, requesting a free passage for Raymond and his family to New South Wales because of their misfortunes in Ireland. This request bore fruit and in 1826 Raymond emigrated to New South Wales. Governor (Sir) Ralph Darling was asked to provide Raymond with a suitable colonial appointment and, until it became available, to allow him the means of subsistence.

9

In 1829 he was appointed Postmaster General.

At the time of Margaret’s arrival in February 1850, James Raymond lived in some splendour at Varroville, near Campbelltown, which he had bought from Charles Sturt and there entertained extensively. He died at Darlinghurst on 29 May 1851 aged 65, and was buried at St Peter’s, Cook’s River. He and his wife Aphra had seven daughters and four sons, of whom James and Robert Peel held positions in the Post Office and William was a landholder at Bathurst. However, there are no records that any of these Raymond cousins made any effort to look out for Margaret or to get her any employment. A month after arriving, having been apprenticed to John Beit in Sydney, he asked to be relieved of her ‘because she is insane’.

10

She was then sent on to Moreton Bay and can’t have been too ‘insane’ as she was immediately indentured to the Import Agent and later Chief Constable, G. Watson. Margaret married Patrick Ambrose, an Irish convict, in the Church of England at Ipswich in 1852, and after his death, in 1861, she married again to David Kynoch. Margaret lived until 1912 and died at the ripe old age of 89.

Another Listowel girl who claimed her father was in Sydney was Bridget (Biddy) Ryan. Biddy was the last name on the list selected by Lieutenant Henry, so we would have to presume that she met the rule of being at least one year in Listowel Workhouse, but on arrival in Sydney she gave her ‘native place’ as Bruff, County Limerick. Her father was called Lancelot (Lanty) Ryan. He had been a soldier but he had been convicted of being a bigamist and, aged 35, he was tried in July 1837 at Limerick Assizes and sentenced to seven years’ transportation. In a report of the court case in the

Limerick Chronicle

of 12 July 1837, Fr Halpin PP Bruff, stated that he married ‘the prisoner’ to Mary Hynes (Biddy’s mother) in Bruff and F. Lyddy PP, stated that he had married ‘the prisoner’ to Jane Huddy in Abbeyfeale at a later date. ‘Jane Huddy deposed that she had married the prisoner and that six weeks later his former wife walked in with her family’.

11

The convict ship

Neptun

e which departed Dublin on 27 August 1837 for the 128-day voyage to Sydney listed Lancelot as having two children, one male and one female, he was a soldier labourer, and was blind in his left eye.

12

It is possible that Biddy may not have known of her father’s conviction. He should have served his sentence and got his ticket of leave by 1844 but we have no record of their ever meeting.

Another interesting ‘selection’ from Listowel was Julia Daly. On arrival at Sydney on

Tippoo Saib

on 29 July 1850, Julia gives her native place as Tralee and her religion as Church of England. She could read and write and said she was a dressmaker. However, her baptismal certificate giving her father as Henry O’Daly and her mother as Elizabeth Howard is registered at the Catholic parish church in Tralee. Julia Daly was named in a court case reported in the

Sydney Morning Herald

13

under the Masters and Servants Act. She was accused of absconding from her employer, a Sydney solicitor named Mr McCulloch of Elizabeth Street, and bringing with her another of the orphans, Mary Connor, also of Listowel. The evidence was not in dispute and it appeared that Captain Morphew, who was the Captain of the

Tippoo Saib

, on which they had arrived, settled Julia in ‘a furnished house in Newtown’ with Mary Connor as their maid and he had represented Julia as his wife. By the time the case came to court, Captain Morphew had sailed on the return journey to England. While no doubt there were repercussions for his career as a responsible ship’s captain, it was the Irish orphans who bore the brunt of the disapproval of the courts and newspaper.

The author’s kinswomen Catherine Mullowney [

sic

] is another mystery woman. She was the daughter of William Mallowney [

sic

] and Honora Doherty and was baptised in Killarney on 6 April 1830. Her parents had married in the parish church in Killarney on 1 October 1826 and she had brothers and sisters. How or why did she end up in Listowel Workhouse, recording on arrival that her father was ‘living in Listowel’ and her native place as Millstreet, Cork? She also stated that she had two cousins, James and Denis Mullowney, living in Sydney.

The Kenmare girls had the highest number of what we would regard as real orphans. Only Catherine Sullivan’s parents were both alive. Both parents of twenty-two of the Kenmare girls were dead, while Jessie Foley and Margaret Murphy’s mothers were ‘living at Kenmare’. Kenmare also had the highest number of those who could not read or write. Only Jessie Foley, Frances Reardon and Ellen Lovett were literate.

We can take it that the majority of these Kerry girls came from homes where parents had either died or deserted, or the parents had not married. There is no doubt from what we know of conditions in their localities that starvation and fever had decimated their communities; they either entered the workhouse with their families, some of whom would still have survived there, or they were abandoned by one or other parent in the hope that they would get food and shelter that the parent was unable to supply. Their lives for the previous four years would have been a constant search for food and shelter. They would have wandered through their local townlands, eventually making it to their nearest workhouse, shoeless and usually dressed in rags. We have the testimony of the Quakers and William Forster in particular, who after his tour of Ireland in 1847 issued an appeal to the women of England to make, prepare and collect clothes to send to the Central Relief Committee for distribution among the destitute in Ireland. ‘Many more of those visited [by the Quakers] were widows with young children. In most cases the families had no food, no beds, no fire, little furniture and hunger was so far advanced that many nursing mothers had ceased to lactate. Shortage of clothing was also seen as a problem, as the heads of the families were unable to seek work when they did not have adequate clothing’.

14

There is no doubt that the inmates of the workhouses and in particular these young girls were there only because it was a last resort for food and shelter and that they were deserving of the opportunity to get out and start a new life on the other side of the world. Whether they were equipped to take on the tasks that awaited them there is another question, though their background, with its deprivations and challenges, would have prepared them for the pioneering spirit which would require ‘plenty of honest perspiration and unglamorous toil, a quality of silent heroism and the capacity to endure heartbreak’

15

that Sid Ingram said of later Irish emigrants to Australia.

Margaret O’Sullivan (Cooper)

Margaret O’Sullivan left Kenmare Workhouse on 6 December 1849 initially travelling to Plymouth and then to Sydney. She travelled on the

John Knox

, arriving on 29 April 1850.

We know from the note on the Kenmare Board of Guardians Minutes that Margaret was from Kenmare East Division. When she arrived in Sydney, her arrival papers tell us that she was aged 20, her parent were ‘Connor & Mary, both dead’. She could not read or write and had ‘no relatives in the colony’.

Kilgarvan is a village in south-east County Kerry near the Cork boundary. It is mountainous country with little fertile land. Sullivan is by far the most common name in that part of Kerry. In Griffith’s Valuation of 1852, there were eighty-seven families of Sullivan or O’Sullivan in Kilgarvan parish. Many of these Sullivans are descendants of the O’Sullivan Beare Clan. Their castle at Dunboy was besieged by English forces in 1602, when their leader Donal Cam O’Sullivan Beare, Prince of Beare – a Gaelic princely title – was defeated and the entire garrison killed or executed. The story of the epic journey of Donal and 1,000 of his followers, who fled north to Breffne, on foot, in the depths of winter, has been kept alive in plays and books for the past 400 years. When they reached their destination only thirty-five had survived.

Margaret’s baptismal certificate of 15 July 1829 gives her home address as Keelbunau [

sic

], Kilgarvan and her parent are named as Cornelius and Mary Sullivan. We have ascertained that her family were known as the Sullivan (Coopers) to differentiate the many different Sullivan families in the area. In Griffin’s Valuation 1852, we presume that Cornelius had died as it was Mary Sullivan who was leasing 76 acres, 1 rood and 9 perches, shared with one other, from the immediate lessor Richard H. Orpen. While Margaret’s arrival documentation says that her mother was dead, this may have been a necessary story to immigration as this was, after all, the Earl Grey ‘Orphan Scheme’.

In 1849 in Kilgarvan, most of the families living there were subsistence farmers, eking a living out of their small plots. We don’t know what happened to Margaret’s parents – did they reach the workhouse and die there from disease or hunger or did they die at home and as a result Margaret had no option but to enter the workhouse? There was great distress in this area during the famine.

The Kenmare girls starting out for Cork must surely have had mixed emotions. They were leaving all they were familiar with, in the depths of winter, travelling by horse-drawn cart through some of the worst affected famine-stricken districts of West Cork to be put on a boat at Penrose Quay in the city, an experience that must have been as frightening as it was exciting.

After the usual short stay in Plymouth they departed on the

John Knox

for Sydney. Shortly after arrival in Sydney Cove, Margaret, with others from the same

ship,

was put on a steamer and sent north to Moreton Bay. This district in those early days of free settlement was a rough, tough place and many of the Kerry ‘orphans’ who arrived there and were placed, had trouble with their employers. There are many Court cases reported in the local newspapers where girls were accused of absconding or being ‘insolent’ towards their mistresses. The girls were well able to defend themselves and in most cases succeeded in getting their indentures cancelled, which gave them the opportunity of moving on to other, and hopefully better employers. They also probably quickly realised that they were being paid below the going rate. Margaret would have been paid £10 with her board, but we know that in 1850 single females were getting £15 to £20, depending on their previous experience.

In any case, the majority of the girls were married within a year or two of arrival. Their husbands were generally older men and almost all were ex-convicts – Tickets of Leave men. They were shepherds, bushrangers, drovers and stockmen and a few were squatters. The girls moved with their husbands from station to station depending on the work and the work depended on the weather – drought, floods, fire all affected economic life. Trevor McClaughlin, in his seminal work

Barefoot & Pregnant?,

outlines very clearly the advantages as well as the disadvantages of being sent to the Moreton Bay district. He explains that the Irish ‘orphans’ in Brisbane in 1851 were in the ‘midst of a supportive community’.

16

The entire white female population at that time ‘numbered only 1,053; the Irish orphans were a significant proportion, constituting approximately 10 per cent of the total. The local Catholic priest, Fr Hanly, contributed to their ethnic cohesion, he apparently attended court when they appeared’.

17

Noni Rush, Margaret’s great-great-granddaughter tells us about Margaret’s life in Australia:

We have no record of where Margaret was apprenticed but we know that she married Edward Sullivan ex-convict within six months. They were married in the Catholic Church in Ipswich, in January 1851, both putting their X mark on the register. The witness at the marriage was Mary Penn. Mary had only just married John Penn in December 1850. Her maiden name was Mary Lovett. A Mary Lovett had arrived on the

John Knox

with Margaret – she was an orphan as well, native place was listed as Meath. I have also positively identified John Penn as being a convict whose ticket of leave in 1846 required him to stay in the Moreton Bay district. He was quite a bit older than Mary and from Gloucestershire.

At the time of writing, I am still uncertain about Edward Sullivan, who was definitely Irish and a convict. There are a number of ‘Edward Sullivans’ all convicts transported from Ireland and it is difficult to say with certainty, almost two hundred years later, which one Margaret married. It must have seemed to her though that she was getting the ideal husband – her namesake – a Sullivan from Ireland. However, it turned out that he was not the best material for a husband and the marriage did not last long.

Edward and Margaret seem to have parted company sometime after their children Edward and Ellen were born in the 1850s and from 1860 she lived with James Cosgrove, also an ex-convict. He seems to have been a decent man and treated her well.

James however, had a chequered background also. His parents were John Cosgrove and Eileen Mulvaney, from Carrickadhurish, Longford, Co. Westmeath. He had been convicted at Longford Assizes on July 1839 of being complicit in the murder of his Grandfather James Mulvaney. His Uncle James Mulvaney Jnr, was convicted of the murder and sentenced to hang and he was executed on 3 August 1839. James being only 14 years at the time was sentenced to transportation for life.

Reading reports of the case which was heard in Longford, there was no direct evidence that James was culpable, other than he knew what happened and may have been present at the time of the murders.

18

James Cosgrave: Alias: Cosgrove | Religion: Catholic |

Age on arrival: 15 | |

Marital status: Single | |

Calling/trade: Errand boy | |

Born: 1825 | Native place: Longford Co |

Tried: 1839 Longford | Sentence: Life |

Ship: Nautilus (2) [1840] | Crime: Murder wilful |

He left Kingstown 17 September 1839 on the ship

Nautilus

with 200 other convicts. One of the convicts died on the journey. They arrived in Port Jackson February 1840, and almost immediately departed for Norfolk Island on 22 February 1840, with 199 convicts on board. Norfolk Island, a notorious penal settlement was a small island in the Pacific between Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia, which had been colonised by the British in 1778.

Margaret and James Cosgrove settled initially at Blue Nobby Station. They had a number of children but never married, presumably as Margaret was already married to Edward Sullivan. This must have been a slur on respectability in Australia as it was in Ireland and they went to immense efforts to cover it up. They may also have been covering up James’ colourful background. In this effort, she often used her former patronymic name of Margaret Cooper rather than Margaret Sullivan, on her children’s certificates, leading her descendants, even her immediate family, to believe that her name was Margaret Cooper from Kerry. However, when she died in 1914, her death certificate was in the name of Margaret Sullivan, which of course was her legal married name.

Noni Rush continues the story:

Margaret’s life with James was the typical station life – I can only surmise as to when they went to Toenda, but I think James Jnr., bought it and took his parents there to live with his family – it’s also interesting to note how the parish map has recorded James Cosgrove as James Cosgrove Jnr, inferring they were well aware they had to distinguish between father and son. The shepherd’s life in the early days before fencing could be isolated and often dangerous – stations were like small towns with the main homestead and cluster of slab huts, a central store for buying extra goods besides your weekly rations (typical rations could be 10lbs. of salted mutton or beef, 10lbs. of flour, 2lbs. of sugar and ¼lb. tea) – later schools started to be seen as essential – sheep could be divided into flocks of about 1500 – each shepherd took his flock out about an hour after sunrise and remain with it all day, keeping the flock together, finding good pastures and protecting it from dingoes and human marauders – at night they would combine a couple of flocks and make fences out of brush hurdles and a watchman would guard them – the wage would have been roughly about 20 pounds per year

As James was always documented at Blue Nobby as being a shepherd, this was what his life would have been like in the early days – it is possible they could have lived away from the central homestead, but all in all not a bad life to what they would have had in Ireland! Later when they introduced fencing his working life would have changed, but I’d say it would have always have been a station labouring life – the men depended on the women to raise the children and do all those household chores, tending a garden etc. – if anything happened to the mother, a man had to find a woman very quickly to replace her for the children’s sake because these stations were vast.

I don’t know if James and Margaret ever acquired their own land or if it was just James Jnr who acquired Toenda – on each of James Snr’s death certificates he is described as both a labourer and a grazier.

From such humble beginnings for both of them they and their children became successful, well-known and respected members of their community. After a very bad start, James Cosgrove does not appear ever to have been in trouble once he came to Australia – and after a maybe rocky start in the colony for Margaret, once she teamed up with James she seemed to be able to settle to raising a family in a stable environment.

I loved to be able to see that she helped my great-grandmother, Ellen, have her babies – Ellen would have had plenty of people around her at both Tulloona and Yallaroi stations (they were huge stations) but it was her mother who came over from a nearby station (possibly still at Blue Nobby in the 1880s?) to be with her – this would also have to mean Margaret was quite adept at assisting with births.

Any of Margaret’s children that I have been able to trace did well in life: Her firstborn, Edward (Uncle Ted), owned land at Boomi and brought up a large family with his wife Martha – when Edward married it was at Ellen’s father-in-law’s house so everyone must have been very close – the Schmidt’s had worked for years on Yallaroi

Station.

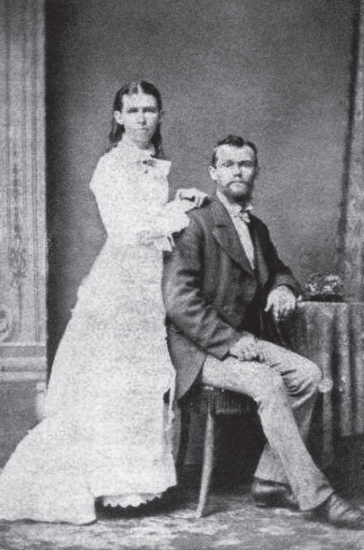

Margaret’s daughter Ellen and her husband.

My great-grandmother Ellen, Margaret’s eldest daughter, became a housemaid at Tulloona Station and married the carpenter, John Henry Schmidt – they must have been valued employees to have been married in the homestead. Theirs was a very successful partnership with John Henry working at Tulloona

and Yallaroi

until they purchased their own land in Boolooroo Shire in 1898. Tulloona is a homestead on the banks of the Croppa Creek in north-east New South Wales. Its closest capital city is actually Brisbane in Queensland about 330km to the east-north-east with Sydney about 570km away to the south of Tulloona. Likewise Yallaraoi was a 202,000-acre station in 1840 and is located in north-east New South Wales.

Even though Ellen was illiterate all her life, I can see from a couple of letters she dictated, that she had quite a sharp mind for farm business – she carried on with the property for a number of years after John Henry’s death, helped by her sons.