Kerry Girls (19 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

In the Australian cities of Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide an aspiring middle class was emerging with new ambitions and requirements. The advertisements in the daily newspapers were offering for sale not only expensive ‘Parisian millinery’ and ‘superior French vinegar’ but also ‘rosewood pianofortes, and very superior violins’. There were advertisements for silks, satins and velvet bonnets richly trimmed in the latest fashion.

1

Even in outlying towns there were requests for trained and experienced staff:

WANTED, a respectable person as Governess for a family in the town of Bathurst, competent to impart a sound English education, with Music and Drawing, references will be required.

WANTED, for the country, a Governess competent to teach French and Music besides every other branch of a solid Education.

2

It was a time of great change, unlimited opportunity, but also many dangers in this new world, when the Kerry orphans set foot in Australia.

Unfortunately the selection of the first lot of orphans to arrive from Ireland on the

Roman Emporer

and the

Inconstant

would appear to have been carried out without much attention to the rules prescribed regarding age (14–18 years) and suitability, of the girls for their new lives. Religion also reared its head early on. When the

Roman Emporer

docked in Adelaide in October 1848 with orphans from Belfast, Cookstown, Dungannon and Magherafelt workhouses, a report in the

South Australian Register

tells us that ‘This splendid emigrant ship has made a passage of less than three calendar months from England. The orphans were Irish girls from the Union houses of the North of Ireland, and professed Protestants’.

3

The paper continued with its views that the Irish orphan scheme was ‘not only a fraud upon the colonists, but as fraught with the most serious evils to the legitimate emigration scheme and to the social and moral interests of the community’.

4

To drive home the message, the paper also reported the views of a British MP who had visited the ship on the eve of her departure: ‘They are a rough lot.’

5

When the second group of Irish orphans arrived on the

Insconstant

on the 7 June 1849, it was the orphans’ suitability for the labour market that was criticised. It was reported in a letter from the Children’s Apprenticeship Board to the Colonial Secretary’s office ‘that only about 35 can milk cows and the remainder show no disposition to learn, many of these also know nothing of washing of clothes’.

6

These reports did not affect the hiring of these first girls, as most of them had been hired within two weeks.

Working life in Australia for the Irish girls arriving was governed by a strict apprenticeship agreement signed by the apprentice and her employer and properly witnessed. Only someone ‘qualified by their clergyman’ could supposedly hire one of the girls. If a girl was under 18 years of age, ‘the engagements must be by indentures … and those indentures will continue in force until the servant arrives at the age of nineteen’.

7

Those girls aged 18 years and over were to be hired as prescribed by the Hired Servants Act. The rules for payment were: for girls of 14 years and under 15 years were to get £7 per year, between the ages of 15 and under 16 years it would be £8 per year and anyone under 17 years was to get £9 per year. All the girls above 17 years would get £10 per annum. Judging from the contracts entered upon by the Kerry girls, this pay scale was strictly observed by the employers. If one of the girls wanted to get married, permission had to be sought.

To the Irish orphans arriving, this pay rate seemed to be very generous and beyond their wildest dreams, but we know from comparisons with the going rate it was very low. With hindsight, the orphans were not trained so they would have probably merited a lower rate in any case, but when the rate was initially set, the colonial administrators were expecting to get fully trained/experienced domestic staff at cut prices. At the time that this payscale was drawn up, another Irish girl (not one of the Earl Grey girls), Mary McCarthy of Shanagolden, aged 21, was writing home to Lady Monteagle, who had helped large numbers of families to emigrate to the Melbourne area, telling her that she was getting £14 a year as a housemaid and another Monteagle emigrant, Michael Martin, reported ‘single women gets from £15 to £20 (with their board).’

8

Mary Brandon

Mary Brandon was in Listowel Workhouse, and on her departure for Australia, her address was given as Newtownsandes. However, on arrival she herself gave her address in Ireland as Ballylongford. She was aged 16, could read and write and her parents, Thomas and Mary Anne, were ‘both dead’. While there are a number of Brandon families in the Tarmons and Ballylongford area, despite an extensive trawl through baptismal records in both Ballylongford and Newtownsandes, County Kerry, from 1829 to 1834, I could not trace Mary’s parents or a baptismal certificate.

Mary was again one of the lucky girls who departed on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

from Plymouth on 28 October 1849, arriving in Port Jackson on 3 February 1950. During the voyage, she and the other girls from Listowel and Dingle were under the supervision and care of Surgeon Superintendent Charles Strutt. She was even luckier to be one of the girls who travelled with Surgeon Strutt on the journey to Yass, and he carefully arranged placements for his charges at locations along the way. However, they were only on the road a couple of days when disaster struck. Two of the drays crashed into each other and in the accident, Mary Brandon and Mary Conway (both Listowel girls) were thrown off and the wheel went over their legs. Strutt had no option but to leave the girls behind in Camden, but not before he put them in the care of an Italian priest – Fr Rogers.

Mary’s great-great-grandson Neal W. Chiddy relates:

After Mary Brandon and Mary Conway were left behind at Camden in the care of Revd Ruggiero Emanuel or as his name had been anglicised, Father Rogers, both girls were in a state of shock and disbelief at their predicament. After travelling so far and their final destination only a few weeks away, the thought of losing the only friends and people they knew was devastating. True to his word Father Rogers tried his best to calm and settle them down, finding accommodation and care for them both. He visited them regularly and when they were well enough he found positions of employment for them. Mary Conway was in service for a settler at Appin some twenty odd miles from Camden. Mary Brandon’s leg had not quite healed so he found a position for her in Camden.

Mary Conway settled in well at Appin and only visited Camden infrequently. She eventually married her settler and they moved from Appin and settled in the Wagga Wagga district. On Sunday 28 of April Dr Strutt visited Mary [Brandon] at Camden. He was returning to Sydney after seeing all his girls were happy and settled in their new homes in the vast Yass district. He found Mary very unhappy; she completely broke down when she first saw him. When she had calmed her down and they had spoken for some time he realised he couldn’t leave her without trying to help her. She had told him she wanted to travel to Yass to be with people she knew. He decided that he would travel to Campbelltown and speak with Fr Rogers. A few weeks later Mary, in company with Fr Rogers, was on her way into the Burragorang Valley where she was put into service with an Irish family, Charles and Mary Collins. Both had been convicted to seven years’ transportation: Charles in 1835 and Mary [

née

Donovan] at Tipperary.

Surname: DONOVAN; First name: MARY;

Sex: F; Age: 24; Place of trial: County Tipperary; Date of trial: 27/12/1837;

Description of crime: Larceny; Sentence: Transportation 7 yrs.

9

When our Mary joined the family she was treated more like a daughter than a maid. From the day she arrived until the day Mary Collins died in 1890 whenever Mary (Brandon) needed help she was there. The Catholic Church was not far from the Collins farm which they both attended regularly. It was at this Church where she met Henry Chiddy.

Henry Chiddy was born at St James Parish Bristol 1823, his parents were Henry and Mary, who were married in 1819 and there was a sister born in 1820. Henry’s father remarried in 1828 to Mary Ann in St James Bedminster. His mother died sometime between 1823 and 1828. Henry’s father died of tuberculosis he may have been infected by nursing his wife. The family was really in trouble; his father, being a stonemason, would have been unable to work.

Henry was arrested on the 5th March 1835 and charged with stealing the goods of Charles Wintle and was ordered to be imprisoned at hard labour for three months. He was released on the 14th of July 1835. He was again arrested on the 19th of November 1835 for stealing candles to the value of 8 pence and was sentenced to transportation for 7 years. His son John said his father always maintained he was innocent of this charge and was sitting on the side of the road when arrested.

Henry was transferred from the local goal onto the hulk

Justitia

and after being examined by a doctor he was transferred onto the convict transport

Lady Kennaway

a short time later. The doctor’s report states ‘Henry Chiddy age 13 years was in good health and was well behaved’.

The Lady Kennaway

departed Portsmouth on the 11th of June 1836 and on the 12th of October 1836 they entered Sydney Harbour, the next day Henry was transferred to the juvenile prison where new indents noted he was 16 years. Why this was done I think was that it was easier to assign a 16 year old than a 13 year old. Henry was quickly assigned to Patrick Carlon of Irish Town on the outskirts of Sydney. Patrick Carlon had been granted 80 acres of land in Burragorang Valley and he and Henry regularly travelled there to clear land and prepare for the Carlon Family to move down there. Patrick Carlon was Catholic and missed not having a church in the area and so he donated land in order that a church could be built. In 1836 there weren’t many people living in upper Burragorang but there were enough Catholics and they rallied around to build their church. Henry being a Protestant was encouraged by Patrick Carlon and the visiting Priests to convert to Catholicism and on the 26th of July 1840 at St. John’s Church Campbelltown he did so.

Mary Brandon.

On 8 October 1841 Henry was given his Ticket of Leave. A letter from Colonial Secretary’s Office states:

Is His Excellency’s the Governor’s pleasure to disperse with the attendance government work of Henry Chiddy was tried at Bristol 2nd sessions 4th January 1836 for seven years arrived per ship

Lady Kennaway

in the year 1836 and to permit him to employ himself (off the stores) in any lawful occupation within the District of Yass for his own advantage during good behaviour.

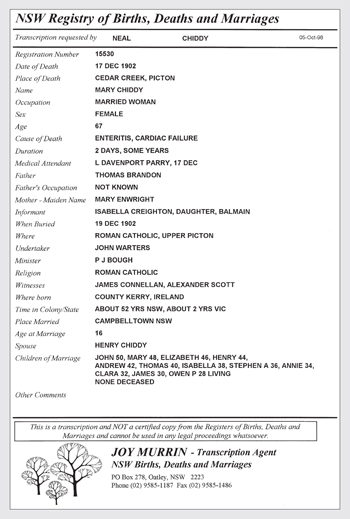

Mary Brandon Chiddy’s death registration, 17 December 1902.

Mary Brandon’s death certificate.

Henry remained in the Yass district for only for two years and then moved back into Burragorang Valley where he had a lot of friends and he felt at home there:

In 1850 while attending Church at Upper Burragorang he met Mary Brandon and on the 26th of September 1851 they were married in St John’s Church Campbelltown. Henry purchased 34 acres of land on a section of the Tonally River know as Tin Kettle Creek and not far from the Church and the Collins family. He built a house and cleared the land, planting fruit trees, some that were still there in the 1950s when the old house was pulled down and the old fruit cut uprooted before it was flooded by the rising waters of the Warragamba Dam. Even though Henry and Mary sold the farm in 1853 it was still known as Chiddy’s Farm until the day it was pulled down. They raised eleven healthy children there and as there were no schools Mary taught them the three Rs. She also taught them to play the Fiddle, two of the boys had bands James in Burragorang and my great grandfather Andrew at Thirlmere with his son Brandon.

Henry and Mary moved from their beloved farm at Tin Kettle Creek – I love that name, apparently when the fist explorers went into the valley they found a tin kettle with a large hole in the bottom on the bank of the river – Mary was having heart problems and needed to be closer to a doctor, there weren’t any doctors in the valley, so they sold their farm and bought a 120-acre farm at Cedar Creek not far from Picton where there was a Catholic Church. They lived there in semi retirement for the next twenty years.

Mary died on the farm on the 17th December 1902 of Enteritis, and heart failure, and was buried in the Upper Picton Catholic Cemetery. Henry died on the 8th of June 1909 at his daughter Elizabeth’s home in Picton and was buried next to Mary in Upper Picton.