Kerry Girls (20 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

The

South Australian Register

reported on the arrival of the

Elgin

with the Killarney girls on board, in 12 September 1849 ‘The female orphans on board the

Elgin

expressed themselves highly satisfied with their treatment, and the Captain says he has not a fault to find with the young women.’

10

However, over the previous year, partly due to the inbuilt prejudice to girls who had been introduced to their colony from workhouses, partly due to the reports issued in their newspapers warning that the colony would become a receptacle for ‘thieves, bastards and prostitutes’, the placement of the orphans in suitable employment was very slow. A minority of the girls from the previous two ships had not covered themselves in glory.

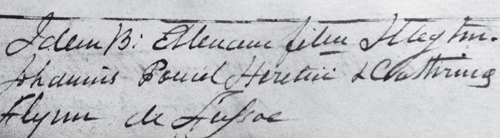

There were girls from Skibbereen, Fermoy, Lismore, and Clonmel Unions as well as Killarney among the 190 who arrived in Adelaide on 12 September 1849. Unfortunately any list of names and corresponding workhouses does not survive. We are left with trying to identify the Kerry girls from their names in the Kerry Catholic baptismal records and nineteen girls were provisionally identified. Of these, only three are positive. Mary Healy and Ellen Powell, both from Killarney and Ellen Leary from Glenflesk, have been definitely identified by their descendants. Gayle Dowling, Ellen Powell’s great-great-granddaughter visited Ireland and was present in Kilrush at the National Famine Commemoration in May 2013. She collected Ellen’s baptismal records from Killarney but was taken aback to find the following written in Latin: ‘

Idem B: Ellen filiu illegtimus Johannis Powel Heretic & Catherina Flynn de filia

.’

John Powell, Ellen’s father, appears to have been an overseer or agent of Lord Kenmare. ‘John Powell, was in possession of two properties at Scrahane at the time of Griffith’s Valuation. Roseville Cottage, valued at £8 was vacant while the second property was leased to Capt. John Kenny. Bary states that the house may have built and used by Lord Kenmare for one of his agents.’

11

The baptism certificate of Ellen Powell, Killarney, 4 December 1826.

Three days after the

Elgin

arrived at the port of Adelaide, the Office of the Children’s Apprenticeship Board, who were responsible for the girls, advertised on Saturday 15 September:

The

Elgin

, with female orphans, arrived. Applicants desirous of availing themselves of their Services, are requested to attend, in person or by proxy, at the Office of the Secretary, Native School, on and after Friday next, the 14th instant. It is recommended that the orphans be removed immediately after the arrangements have been made. Signed M. MOORHOUSE, Secretary to the Board.

12

The negative publicity, together with stories of misbehaviour of the girls who had arrived on the two earlier ships, whether true or false, meant an unwelcome environment awaited the

Elgin

group. While a number of them had been moved to the Native School for hiring, some must also have also been kept on board the ship, which delayed its return to London. By 29 December the

Elgin

was still in Port Adelaide awaiting loading. Most of this delay was attributable to the delay in finding places for the orphans.

13

Further accusations of immoral conduct, ‘Bacchanalian orgies’ and allegations that the Native School was being run as a ‘Government Brothel’ were levelled at the orphans while in this Depot, and were in turn refuted by the Children’s Apprenticeship Board.

On Saturday 20 October the

South Australian Register

reported on a case where a local farmer had used threatening and abusive language to a publican and was also charged with an assault on Johanna Donovan, one of the

Elgin

girls. Mr J.J. O’Sullivan, who acted as schoolmaster on board the

Elgin

, spoke in Johanna’s defence. He said he:

thought the case too serious to be disposed of summarily, adding that it had been stated in the papers that more than 21 of the Irish orphans were on the town. No wonder, if they were treated as this one had been! His official duties had ceased but he considered himself morally bound to afford the poor girls such protection as was in his power.

14

Johanna, giving evidence stated that she had arrived on the

Elgin

about three weeks previously.

A person, whom she could not identify, engaged her at the Depot on the 10inst. Whilst walking with him from the Depot, he told her that he had hired her as a married man, but he was not, and he was going to get rid of the old women he was living with, and he wanted her heart and hand and not her service. She rejected his proposals and said she would not live with him that way as she had nothing but her character to depend on. He replied he had plenty of money and if he did her any harm he would pay her well for it. He offered her some spirits from a bottle he had with him and asked her to unfasten his waistbelt; then he began to pull her about and tried to kiss her.

A witness came along at this point and, taking stock of the situation, took her on to a house where he knew there was another Irish orphan. Her assailant was bound to appear again the following week.

15

Charles Brewer, immigration agent in Adelaide, replying to a query in the

Register

on the 27 October, said:

there is not sufficient care taken in their selection, the consequence of which is, that many of them are on the streets of Adelaide. The Irish orphans who came out on the

Elgin

, conducted themselves well on the voyage, and are considered by the Orphan Board to have been more carefully selected than those by the

Roman Emperor

or

Inconstant

, but there is some difficulty in getting them hired, the colony being now much better supplied with a more generally useful class of female servants.

On 10 November, Ellen Walsh, who according to the

South Australian Register

‘came out on the Elgin’, was in court accused of stealing £5. The witness in court said that Ellen, having ‘left her place, she was allowed to sleep there [in the witnesses’ rooms] for the night’.

By August 1850, the Irish orphans were still making headlines. ‘Catherine Ryan, an Irish orphan per the

Elgin

, was brought up on remand, charged with stealing a brooch and other articles, the property of her employer, August Fischer. No further evidence was brought forward. She made the following statement:

I know I am guilty of stealing the brooch, and the locket; I have nothing else to say. The clothes are my own; I would not have done it, but I had to sleep by the river side for a night. I tried for a week to get a place at Mr Schlesinger’s office and could not get one.

16

The same newspaper on the same page reported:

Mr Morris, keeper of the Lunatic Asylum, brought up an Irish orphan who had been committed to his care, and handed her over recovered to Mr Moorhouse, Secretary to the Orphan Board.

17

It is hard to know where the truth lay but it is obvious from all the inquiries held by the different parties that the girls who arrived on the

Elgin

were not properly supervised in the native school, their prospective employers were not vetted and where there was a disagreement between employer and employee, the employee had no home or no alternative employment offered to her. Any fair-minded reader would say that they were more sinned against than sinners.

An entirely different picture emerges on the hiring of the girls from the

Thomas Arbuthnot

. All the girls were initially lodged in Hyde Park Barracks, Macquarie Street, originally built to house convict males, and it was from here that interested parties could come to hire the girls. One week after the arrival of the

Thomas Arbuthnot

two of the girls had already been hired. Mr Meriewether, the Emigration Agent, decided to send a number of the girls on into the interior towards Goulbourn and Yass where there were now a number of settlements and stations who would, no doubt, require labour as a result. Charles Strutt, who had been their surgeon superintendent on the ship, offered immediately to go with them and see them into employment. He asked for volunteers and ‘130 expressed a wish to go to anyplace that I might be going to’.

18

The girls had been cooped up with nuns in the barracks since they arrived and Strutt perceived a ‘gloomy, quiet and silent atmosphere’.

19

He felt that the girls had enough praying and wanted to get going to the country.

We believe that at least eight Listowel girls and nine of the Dingle girls went on this further journey with Strutt.

Eventually 108 girls, with at least three matrons (Miss Collins of Listowel and others unnamed), left the barracks and went by steamer to Paramatta, where they lodged that night in the former convict barracks. The following day, Tuesday 19 February, they set out on their journey in fourteen drays drawn by a team of horses. Strutt continued to keep his diary, recording the minutiae of the days as they travelled along the rutted track which was then the forerunner of what was later the Hume Highway. The girls slept outdoors in the bush in makeshift tents with the matrons, subject to insect bites, with parrots, magpies, and cockatoos overhead to wake them early in the mornings. Strutt slept under a dray with the men and drovers and was ‘much tormented by ants, flease [

sic

] or some such creatures that bit like fury’.

20

He helped to cook and serve their food, meat, potatoes and tea as they travelled. Rations were picked up every few days at stops along the road. ‘Little water to be found, and that not good, and far apart.’

21

They were only on the road two days when disaster struck. Two of the drays crashed into each other and in the melee, Mary Brandon and Mary Conway (both Listowel girls) were thrown off and the wheel went over their legs. Strutt had no option but to leave them at Camden where the accident occurred, under the care of a surgeon magistrate whom he judged to be ‘rough and uncouth’.

22

The two Mary’s were heartbroken at being left behind, shocked after the accident and now parted from their friends and colleagues with whom they had shared their lives for the previous four months. However, an Italian priest who witnessed the accident guaranteed Strutt that he would look out for them and that they would be well cared for. The very next day, having stopped for the night, Strutt recorded in his diary ‘Thurs 21

st

Stopped for the night at the Haunted Hut, wrote a letter to my two girls’.

23

On Saturday the 23 February, they approached their first signs of civilisation – Berrima, where the girls got their first sight of ‘blacks’ as Aborigines are referred to at this time. ‘A tribe of blacks were encamped there and frightened the girls’.

24

Goulbourn he found a ‘dull, quiet place, with perhaps a 1000 people, two churches, a catholic chapel, a Methodist chapel, a large gaol, a courthouse and several inns’.

25

On Thursday 1 March, they camped by the river near the home of Hamilton Hume, who was the first to cross the country from Sydney to Melbourne (Port Philip). They were about to enter Yass, where the first hirings would take place, so they took out their boxes here – the boxes they had brought 10,000 miles from Ireland, to dress up and make themselves smart. A number of girls were hired in Yass, but when Strutt discovered the following day that two had been hired by ‘improper persons’, he promptly took them away. He also had a number of offers of marriage. A ‘watchmaker in the town wishes to have a wife, and has consulted me on the subject. He has taken a fancy to one of our matrons, but the affair will be rather difficult’.

26

Another applicant – ‘a certain Michael Flynn’

27

– made no bones about it and said he was looking for a wife. ‘In five minutes he had selected one’. But this girl was not to be tempted so easily – having given him a false name, she ‘quizzed him very much’. Having discovered he was a Ticket of Leave man, and had no money, Strutt sent him to get signatures from the priest and magistrate before proceeding any farther. Strutt comments ‘he seemed quite surprised at the difficulty, imagining that he had nothing to do but come and take away any girl he might honour with his choice’.

28

By Saturday 16 March, forty girls and two matrons had been hired in ‘decent places’ in the Yass district. It was arranged that another fifteen would stay on there for future placement and Strutt would take the remaining forty-five on to Gundagai. After a tough journey over rough ground, creeks and hills by the Murambidgee river, they reached Gundagai, then a small ‘town’ of 250 people, with a mail car twice a week to Port Philip and Sydney. By Saturday 23 March, he had hired out eighteen girls of those he took to Yass.

Some blacks were walking about the town to the great wonderment of the girls – they were a stout limbed race, with nothing but a blanket about them. One had a boomerang … there are about 200 blacks in the neighbourhood, and about 2000 in the district.

29

He describes how an aborigine man came into the yard of the barracks and one of the policemen asked him jokingly if he wanted a wife. The man said ‘no’, he had three already and they would be jealous. The policeman pointed out Biddy and asked if he would have her. ‘No’ said he with an unmistakable expression of disgust, as if he was on the point of being sick, ‘too much yabber’.

30