Kerry Girls (17 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

Conditions in Adelaide were fairly basic at this time. The town had only been in existence a bare thirteen years. However, both the capital and the state of South Australia had been carefully planned. Land was sold to settlers rather than given away free. Dependable and experienced labourers and farmers were the preferred immigrant, rather than convicts and paupers. It was expected that these labourers would work and save and eventually buy land for themselves and their families. There had been good times and bad times for these settlers, with depressions and droughts but after a series of good harvests, at the time of the

Elgin

’s arrival, Adelaide was a busy centre.

From newspaper reports, it appears that the

Elgin

stayed at its moorings in McLaren Wharf. The road into Adelaide was barely a track and almost impassable at this time, but a certain number of girls must have come into the ‘Native School’, which was the depot from which they could be hired. There seems to have been very little care taken of any of the Irish orphans who arrived in Adelaide and as a result these girls were the ones who had the most trouble in getting employment, in keeping their jobs and generally in behaving in what was known as a ‘seemly manner’.

The second lot of Kerry girls, who departed from Dingle and Listowel the following month, and set sail from Plymouth on 28 October 1849, were by far the most fortunate. Their good fortune was entirely down to one man: the surgeon superintendent appointed, Charles Edward Strutt. Dr Strutt has left us a diary of the voyage and of his later journey with 108 of the girls into the Australian interior.

Seventeen girls from Listowel and twenty from Dingle initially went by ‘cart’ to Dublin. The girls, equipped with their wooden boxes complete with ‘strong locks’, were conveyed to the North Wall to embark on a steamer for Plymouth. On the steamer they met with girls from workhouses in Dublin, Clare and Galway. The

Thomas Arbuthnot

was a fast sailing ship and one of the largest of the emigrant ships taking settlers and migrants to Australian ports in the 1840s and 1850s. The master of the ship was G.H. Heaton.

The voyage on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

was not Strutt’s first encounter with emigrant ships. He had previously served on the

St Vincent

, departing London in October 1848 with Bounty Emigrants for Sydney. These were mostly families and reading his diary of that journey, he had almost constant trouble with a number of the single women as well as some of the single men. Not only was he the ship’s doctor but he was also responsible for the moral and physical wellbeing of all the Government emigrants. As well as refusing to scrub out their quarters, some of the single men were far too keen on visiting the single women’s dormitory after hours. He had solutions for both misdemeanours. He battened down the hatches of the women’s quarters at 8 p.m. each night and any transgression was punished by denying ‘puddings’ to the passenger concerned as well as a stiff talk. His other responsibility meant that he had to ‘settle divers quarrels amongst the emigrants, which is a daily occurrence. I hear both parties and administer a private admonition to the offender.’

9

On Friday 17 November 1848, he reported ‘A grand row took place with an Irish family, which after passing through the usual stages of personal abuse, was nearly ended by personal fighting.’

10

As a surgeon superintendent, Strutt had a wide-ranging job specification. He took his responsibilities very seriously and saw himself as ‘preserving order, securing cleanliness and ventilation’. He believed firmly that keeping the highest standard of hygiene on board would stop a great many of the diseases that were then prevalent, particularly in overcrowded, poorly ventilated places. Strutt was a fair though firm supervisor and he was also a very caring and considerate person.

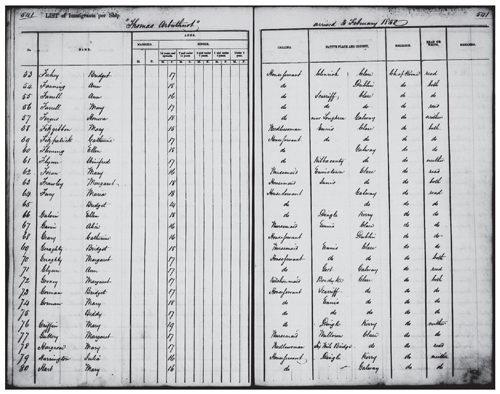

Logbook of passengers on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

,

1850.

Strutt showed his compassionate nature even before the

Thomas Arbuthnot

sailed. On arriving at the depot at the Baltic Wharf, he examined the girls but was not happy with the appearance of a number of them. He ordered ‘a warm bath for a great number of them, and about 130 to have their hair cut’.

11

Having ascertained that the vast majority of the girls were Roman Catholic, on the day before sailing he called on ‘the Romish priest and got a dispensation for the Catholics on board to keep all days alike, and eat meat on fast days’.

12

As well as the diary of Surgeon Superintendent Strutt, we are also lucky to have a record of the voyage of the

Thomas Arbuthnot

written by Sir Arthur Hodgson, described as ‘squatter, politician and squire’.

13

He had been educated at Eton and served in the Royal Navy. He emigrated to Sydney in 1839 and after gaining experience on land in New South Wales had taken the risk of moving north and in 1840 took up land at Eton Vale, the second run on the Darling Downs. He met with mixed fortunes there initially due to drought, low prices and transport difficulties but later became very wealthy and in 1858 he won a seat in the New South Wales parliament. He travelled on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

with his wife and child, returning home to Australia.

By Tuesday 30 October, two days out from Plymouth, due to a swell at sea and constant rain, Strutt reported that ‘about sixty were seasick’. One can only imagine the terror this must have induced in the girls, being tossed around in their bunks, lying on their straw ‘mattresses’, the ship rolling in heavy seas, water pouring in through a leaky deck, pitch darkness in their sleeping quarters, the noise of the goods in the hold sliding and banging off each other. Not to mention the pigs, sheep and fowls on board similarly protesting at their accommodation. Strutt immediately thought about the girls and ‘went down to console and encourage my people’.

14

Hodgson reiterates the seasickness on board, which seemed to affect everyone, but by 4 November, he reports that ‘the worst part of our voyage may now be considered to be over’.

15

He also tells us on the same day that ‘some of our sheep have died, also many of our poultry’.

16

On the

Thomas Arbuthnot

the surgeon superintendent had the extra duty of organising a school for the girls, and on Sundays it was his duty to preach a sermon and conduct a religious ceremony. He was impartial in his handling of all complaints and when there was ‘more noise than was seemly during prayers, I stopped the lime juice of Miss Collins as she would not point out the guilty party’.

17

Miss Collins had been an assistant matron in Listowel Workhouse and she had volunteered to emigrate herself, travelling as an assistant matron on the

Tipoo Saib.

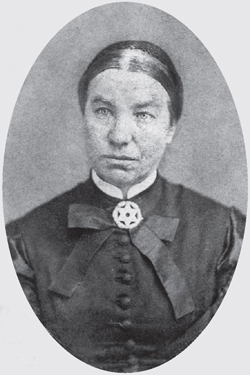

Mary Moriarty

Mary Moriarty was one of the twenty girls selected in the Dingle Workhouse for emigration to Australia under the Earl Grey Scheme. Her older sister Catherine was also selected. Mary and Catherine were daughters of Maurice Moriarty and Margaret Cahalane. On arrival, Mary is recorded as being 16 years of age, Roman Catholic, able to read, and that both her parents were dead. From extant records in the Presbytery in Dingle, we know now that the correct age for Mary was 17 when she arrived, as she was born in 1833. We can see from her life in Australia that she was feisty, quick and intelligent and would appear to have had a good knowledge of English as well as her native Irish.

Mary spent a short time in the reception centre in Sydney before travelling onwards with Catherine and a number of the other Dingle and Listowel girls to Moreton Bay. She was initially indentured to Thomas Hennessy, Breakfast Creek at £7-£8 per year. Trevor McClaughlin relates Mary’s fate with Mr Hennessy:

When Thomas Hennessy complained to the Brisbane bench that his apprentice, Mary Moriarty, had absented herself from his service and listed her numerous faults and misconduct, Moriarty replied with allegations of sexual harassment: ‘Hennessy used to come to the sofa to me every morning and make use of expressions I cannot repeat and because I laughed, he struck me and kicked me down’.

Hennessy’s defence that he had to go to the sofa every morning to get her up ‘or she’d be there ‘till 9 o’clock’ was not strong enough to overcome the court’s suspicions, and the bench cancelled the agreement and compelled Hennessy to pay Mary wages amounting to £1.2s.8d.

Soon after this, on 9 June 1852, Mary married Samuel J. Brassington in Brisbane, then a part of New South Wales. The witnesses were James Fitzgerald and Catherine Moriarty, both of Brisbane. Samuel would appear to have been a convict, arriving in Moreton Bay on the

Mount Stewart Elphinstone

on 1 June 1849, sentenced to seven years at Stafford Quarter Sessions. His crime was ‘larceny of person’ or pickpocket. He received his ticket of leave in Moreton Bay in 1849.

We learn something of Mary’s life from the

Charleville Times, Brisbane

, written in 1947 when one of her grandsons was the Speaker of the Queensland Legislative Assembly:

18

Samuel Brassington and his wife, the Grandparents of the present Speaker of the Queensland Legislative Assembly, Mr. S. J. Brassington, were among the early settlers of the Upper Warrego River. Mr. Brassington took up

Old Killarney

in 1864 and the couple lived in a bark hut surrounded by a stockade, which afforded protection from the hostile natives. Very often ‘Granny’ Brassington as she was familiarly known in later years, had a trying time protecting her family and property during the absence of her husband, who found it necessary to go to Ipswich by covered wagon for the necessary supplies to keep his family and others in the locality, going. In 1870, Mr. Brassington acquired Reynella holding from Messrs. Gordon and Flood, who were also the owners of Gowrie station. He held it until 1891, when the lease expired. He also held Bellrose holding from 1881 to 1889, in which year he sold it to Mr. W. Pennaldurick, who died in the Maranoa district, two years ago at the age of 96. When news reached Mrs. Brassington, by bush telegraph, that there was a white woman (Mrs. Mary Janetzky) living at Gowrie Station (Charleville), she rode down the Warrego side-saddle to make her acquaintance and a ripe friendship existed between Mary Brassington and Mary Janetzky thence onwards.

On Saturday 1 April 1916, the

Brisbane Courier

printed an obituary of Mary Moriarty.

19

PASSING OF A PIONEER

The Late Mrs. Brassington

The death occurred suddenly on St. Patrick’s Day of ‘Grandmother’ Brassington, the oldest Identity on the Warrego, aged 83 years, writes our Augathella correspondent. Deceased enjoyed very good health up to a week previously when she had an attack of dengue fever. She seemed to recover from this and was quite well until St. Patrick’s morning when she donned the colours of her native land – about 12 o’clock, she was discovered unconscious and expired without gaining consciousness.

The deceased lady was born in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland in 1833. Her maiden name was Mary Moriarty. Together with her sister Mrs. Catherine Elliott (who pre-deceased her) she arrived in Australia, in Sydney in 1849 in the ship

Thomas Arbuthnot

, shortly afterwards coming to Queensland where both sisters married. Mrs. Brassington was married in the year 1851 and in that year, she and her husband came to the Condamine and started a shoemaker’s shop. Next they arrived in Roma [Bona?] and then went into an Hotel at Donnybrook. Selling out the Hotel they arrived on the Warrego River in 1865, where they built the first house (an hotel) at Augathella.

Mary Moriarty.

Giving up hotel life Mr. and Mrs. Brassington took over Reynella and Bellrose stations, but owing to had luck and bad seasons this venture did not prove profitable, so they left Reynella and returned to Augathella and opened a store keeping and butchering business.

The deceased lady’s husband pre-deceased her 15 years ago, when ‘Grandmother’ finally retired to Private life. She was known as one of the most generous hearted of women and was dearly loved by all who knew her. She had a family of 4 sons and 7 daughters, of whom 2 sons and 4 daughters are living, together with 69 grandchildren and 52 great-grandchildren. The sons and daughters living are George and Maurice Brassington, Mrs Sarah Ware, Mrs Hannah Creevey, Mrs Margaret Smith (Augathella), and Mrs Bridget Gordon (Morven).