Kierkegaard (14 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

If the pseudonyms represented the array of non-Christian, anti-Christian, or deluded-Christian characters one finds on Christendom's stage, then the

Discourses

were Søren's attempt at straightforward spiritual nourishment. Or were they?

Straightforward

is not a word easily ascribed to Kierkegaard. The

Discourses

are openly Christian in their language and are usually built around reflection on a biblical passage. Yet they are as challenging to platitudinous religiosity as anything else he penned, and they are by no means easy reads. One cannot shake off the suspicion that “S. Kierkegaard” of the

Discourses

might also be a character playing a role invented by Søren Kierkegaard. The

Discourses

counterbalance material found elsewhere, offering different takes on

similar themes. Whatever it is Kierkegaard is trying to say to his readers is not found in any one book or in any one author, named or unnamed. Instead, the truth is found as the reader engages in reflective and dialectical conversation with all the books in the authorship.

The “reader” is a very important aspect of Kierkegaard's output, and he had an active participant in mind when constructing his books. All the

Discourses

bear the inscription:

“To the late Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard formerly a clothing merchant here in the city, my father, these discourses are dedicated.”

Yet Michael, as a dead man, was not the ideal reader Søren had in mind. It is in the May 16, 1843,

Discourses

that we first encounter “the single individual.” In an 1849 journal entry Søren admits how at first this phrase was “

a little hint

to her.” The

Discourses

are replete with messages and imagery that only Regine would understand. They were intended, first and foremost, for her. In the same journal, Søren records how the scandalous “Seducer's Diary” in

Either/Or

was written for Regine's sake, “

in order to clear her out

of the relationship.” That piece describes the callous seduction and abandonment of an innocent girl. Regine was supposed to be disgusted at

Either/Or

and then reassured that the breakup had a spiritual value from reading the

Discourses

. Only later, as the relationship with Regine receded into the distance, would Kierkegaard's “single individual” come to take on the wider meaning of any reader who takes on Søren's challenge for her or himself.

Søren tells us that the pseudonyms and self-named works contained many nods to Regine. But she was capable of making nods of her own.

Søren and Regine often met on the street. They would acknowledge each other with an incline of the head but otherwise they did not speak. On Easter Sunday, 1843, during Mynster's sermon at the Church of Our Lady, these slight actions took on a significance greater than the sum of their parts. “

At vespers

on Easter Sunday . . . she nodded to me. I do not know if it was pleadingly or forgivingly, but in any case very affectionately.” Søren thrashed out the implications of this momentous event in his journals. Her frank actions made Søren suspect that she

saw through all he had done. “I had sat down in a place apart, but she discovered it. Would to God she had not done so. Now a year and a half of suffering and all the enormous pains I took are wasted; she does not believe that I was a deceiver, she has faith in me.” Years later Søren would elaborate on the meaning he had ascribed to this, the most indirect of communications. “

Her eyes met mine

in church. I did not avoid her gaze. She nodded twice. I shook my head, signifying: You must give me up. Then she nodded again, and I nodded as friendly as possible, meaning: I still love you.”

Too many assumptions were riding on too little information. The “conversation” was doomed to fail. The crucial piece missing in this puzzle was something that Regine assumed Søren already knew but of which, in fact, he was completely unaware. For Regine was about to become engaged to her original flame, Fritz Schlegel.

When Søren finally found out the news, he saw the nods in a whole new light. “

After her engagement

to Schlegel, she met me on the street, greeted me as friendly and charmingly as possible. I did not understand her, for at the time I did not know of her engagement. I looked questioningly at her and shook my head. No doubt she thought that I knew about it and sought my approval.” He had meant the nods in church and the street to mean that he still loved her but must pursue his project, encouraging her to stay the course with bravery and perseverance. Instead, Regine had taken the nods to mean he was giving his blessing and release for her engagement. “

No doubt

the decisive turn in her life was made under my auspices.” It bears noting that all the “mistaking,” “loving,” “releasing,” “decisive turning,” and the rest are

Søren's

interpretations of the nods. Of Regine's opinion there is no record.

The incident sent Søren packing, yet again, to Berlin for his second trip on May 8, 1843. The writing break would prove short-lived, but it was there he continued

Fear and Trembling

and altered

Repetition

. Both books bear the marks of Regine's decisive alteration to the

status quo

. It was in Berlin Søren wrote, “

If I had had faith

, I would have stayed

with Regine. Thanks to God, I now see that. I have been on the point of losing my mind these days.” The line illuminates much of the ethos running through

Fear and Trembling

and its heart-wrenching account of a man who gives up what he loves and yet waits, in faith, for it to be returned to him.

Repetition

tells the story of a lovelorn Young Man who returns to a foreign city in an effort to recapture his experiences, only to discover that in life true repetition is impossible. The ending to

Repetition

, especially, reflects a strong editorial hand in the aftermath of Fritz and Regine. A comparison of draft manuscripts and the published version reveals that Søren radically changed the fate of the Young Man. Originally, he commits suicide as a symbol marking the impossibility of ever marrying. In the new version, the Young Man lives on to become a better man, ennobled by the ultimate rejection of his lover.

Like the ending of

Repetition

, some journal entries from this time contain fantasies of benign revenge against Regine. Søren had often claimed that he wanted Regine to move on with her life, but now that it was actually happening, it stung. Søren was hurt and angered by what he saw was her inconstancy. “

But so my girl

wasâfirst coy and beside herself with pride and arrogance, then cowardly.” Here was the woman who once wildly pleaded with Søren, now engaged to the sensible Fritz. In his diaries, Søren tries out various scenarios in which he meets Regine on the street and is able to coolly reprimand her for claiming she would die without him and then getting engaged to another within a year. “

I have loved her

far more than she has loved me,” he tells himself. The entry continues with assurances that his breach with her was a mercy. “I dare congratulate myself for doing what few in my place would do, for if I had not thought so much of her welfare, I could have taken her, since she herself pleaded that I do it . . . since her father asked me to do it.” The exact reason for his chivalrous action is lost to historyâSøren tore this page from his journal. But he saw fit to leave in more assertions that he was “prouder of her honour than of my own” and defends his loving, deceptive break by claiming that marriage to Regine would have been

tantamount to drawing her into his “cursed” life. “

But if I were to have explained myself

, I would have had to initiate her into terrible things, my relationship to my father, his depression, the eternal night brooding within me, my going astray, my lusts and debauchery, which, however, in the eyes of God are perhaps not so glaring . . .” In Søren's eyes, he may have been guilty of breaking her heart in order to save her, but Regine too was guilty of breaking her promise to love him forever. He took steps to remember her declarations, even if she had supposedly forgotten them. To that end, Søren commissioned to be constructed a tall chest made out of rosewood, in which he kept various tokens of their engagement. “

It is my own design

, prompted by something my beloved said in her agony. She said that she would thank me her whole life if she might live in a little cupboard and stay with me. Because of that, it is made without shelves.âIn it everything is carefully kept, everything reminiscent of her and that will remind her of me. There is also a copy of the pseudonymous works for her. Regularly only two copies of these were on vellumâone for her and one for me.”

Statistically at least, brother Peter was luckier in love than Søren. He had married not once, but twice, having wed Sophie Henriette (or Jette as she was called) in 1841, following the death of his first wife, Marie. Since that time Peter and Jette and their son, Paul, had lived in a country parish where Peter served as a pastor of a village church. As a representative of the established state church, it was one of Peter's duties to practice compulsory baptisms of the children of Baptist and other dissenting parents. This practice went against Peter's conscience and his theological association with the Grundtvigian school. Grundtvig was a vocal opponent of the practice, which he saw as religious persecution. Although he too was a senior figure in the official Lutheran church, Grundtvig supported a more

laissez faire

style of populist “People's Church” as opposed to the hierarchical “State Church” model. The position put Grundtvig and his disciple, Peter, in direct opposition to the supreme primate, Bishop Mynster. Their stand-off came to a head

in 1845, causing a minor public scandal. Although he was still something of a “Mynster man” out of loyalty to their deceased father, Søren privately agreed with Peter and urged him to stand his ground. The issue was doubly annoying for Søren, because siding with Peter meant tacitly siding with Grundtvig, of whom Søren had almost nothing good to say whatsoever.

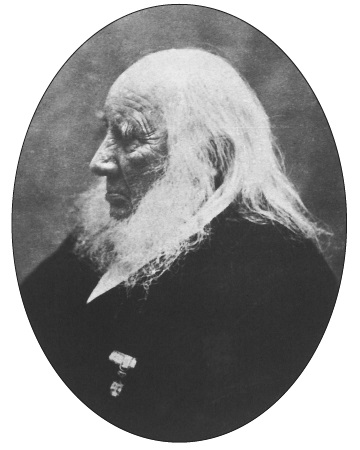

Nikolai Frederik Severin Grundtvig, a towering figure in Danish politics, church life, poetry, education, and nationalism. “The Grundtvigian nonsense about nationality is also a retrogression to paganism,” Søren complained. “It is unbelievable what foolishness delirious Grundtvigian candidates are able to serve up.”

N. F. S. Grundtvig loomed large on the Danish stage. He was a poet, a politician, and a pastor, and the author of endless volumes of history, theology, and hymnody. One of Grundtvig's Big Ideas was his so-called “Matchless Discovery.” For Grundtvig the “discovery” was that authentic Christianity does not reside in holy texts written in foreign languages but instead in the public recitation of the Apostles' Creed and the Lord's Prayer in the native tongue of the people. Another pillar of Grundtvigianism was that different nations in history had been appointed divine tasks. Past ages belonged to the Jews, the Greeks, the Romans, and so on.

Now

was Denmark's time. In Grundtvig's voluminous writing, ancient Norse culture is “baptised” and given revelatory status. Søren is scathing about all this. “

The Grundtvigian nonsense

about nationality is also a retrogression to paganism. It is unbelievable what foolishness delirious Grundtvigian candidates are able to serve up. [ . . . ] Christianity specifically wanted to do away with paganism's deification of nationalities!”

Søren had little time for Grundtvig's bluster and considered his populist rhetoric, which explicitly combined patriotism with Christianity, to be worse than even the intellectualised religion of the cultured elites. His private writing is full of humorous caricatures of Grundtvig and his followers. He was not, however, simply dismissive of Grundtvig on a personal level. The

Concluding Unscientific Postscript,

Søren's

magnum opus

, published February 27, 1846, is, in large part, his provision of a rigorous intellectual, philosophical, and theological answer to Grundtvig's view of Christianity, history, and nation. To be sure, Hegel, Martensen, and others come in for a kicking, but Grundtvig is one of Søren's major targets in the

Postscript

.

But, of course, it is not

Søren

who wrote the book

.

It is “Johannes Climacus” who arranged for this finale to his

Philosophical Fragments

to be published. The massive tome, with its comically complicated chapter headings and bewildering arrangement, signals to the discerning reader that part of the book, at least, is a satire on the style favoured

by Grundtvig and the Hegelians. Not just the content but the physical dimensions are part of the jokeâthe “postscript” is four times larger than the book it is supposed to “conclude.” Readers who are not turned off by the jocular style are led into a

tour-de-force

of intellectual content. The

Postscript

contains some of the best Kierkegaard (or whoever) has to offer and brings to a conclusion many of the themes in development since

Either/Or

. To the stages of existenceâ“aesthetic,” “ethical,” and “religious”âis brought a new form of faithful life. Søren intended this book to be a conclusion, not only to Climacus's works, but to the authorship as a whole. To this end it contains a lengthy section entitled “A Glance at Contemporary Danish Literature,” which is, in fact, a review and a discussion of all the works since

Either/Or

up to and including

Stages on Life's Way

. The “Glance” is attributed to Climacus, but inserted at the end are a few pages deliberately kept separate from the rest of the text. “The First and Last Explanation” echoes the letter that Søren had published in the

Fatherland

before launching his authorship with

Either/Or

years before. In it, he finally acknowledges that he, S. Kierkegaard, is the one responsible for the texts “

in a legal and literary sense

.” He asks, however, that the pseudonyms be treated as essential parts of the work and not as optional extras. “Therefore, if it should occur to anyone to want to quote a particular passage from the books, it is my wish, my prayer, that he will do me the kindness of citing the respective pseudonymous author's name, not mine.”