Kierkegaard (15 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

The wish, the prayer, brought to conclusion Søren's carefully constructed scheme of presenting Christianity to Christendom. The five or so years of ceaseless writing, endless perambulating, lonely living, and prodigious expenditure were brought to an end, and with it Søren intended to renew his long-postponed idea of taking up a quiet pastorate in a country parish. As with every other of Søren's elaborate schemes, however, this one was not to be.

For one thing, he was a writer, through and through, and the parson's life was not for him. For another, the great revelation of the genius behind

the authorship had actually already been made a month before, in a scurrilous rag of a newspaper. In hindsight “The First and Last Explanation” would come to look less like a triumphant

coup-de-grace

and more like desperate damage control for a writing career only halfway finished

.

In 1846, a tabloid campaign against him was brewing, threatening to crack the edifice of the authorship and bring Søren's world crashing down. And worst of all, he had brought it on himself.

Pirate Life

Catrine Rørdam has a lot to answer for. How much pain, joy, anger, humour, boredom, insight, frustration, spiritual reformation, and existential revolution would have been denied if Catrine Rørdam had cried off her hostess duties? How many sleepless nights and ruined careers, how much spilled ink, and how many trees have given their lives as a result of Catrine Rørdam's coffee klatches? It is because of her hospitality that Søren was put into the path of the two people with the most impact on his writing career. Søren first met Regine in 1837 at a gathering hosted by the mother of his friend Peter Rørdam. And it was that same year at another of her soirees Søren first made the acquaintance of a young Aron Goldschmidt.

It is not easy being Jewish and Danish in the nineteenth century. True, there is no outright oppression, and Russian or German Jews have it worse, but that does not take away from the steady unease one feels in Danish society. No matter how well you fight in the army, teach in the university, or write in the pressâany Jewish person in the public eye is always waiting for the other shoe to drop. In Danish Christendom, Danish Jews are considered slightly off. A “cursed race” in popular lore, like Ahasuerus they are doomed to wander as foreigners even in their home lands. A respectable Jew, going about his daily business, is always ready to hear the taunt “Jerusalem is lost!” or to deal with the insinuation that unlike other “civilised” people, he cares only about making money. And woe betide the Jewish man whose concern actually

is

about making money.

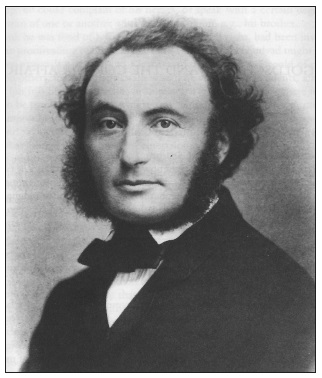

Meïr Aron Goldschmidt. Amongst his many literary projects, Goldschmidt was the principal author and editor of the satirical

Corsair

.

Meïr Aron Goldschmidt is an intelligent, artistic, empathic, and funny man. He is politically informed and a committed defender of free speech. Aron is a novelist, essay writer, and a journalist, and is making a name for himself in radical, reform-minded government circles. He is also adept at wringing a profitable livelihood from his writing talents. Unbeknownst to the wider public, Aron is the founder and secret chief editor of the

Corsair

, a satirical magazine with literary promise and an enormous influence on public opinion. Like many Danish Jews of his generation, however, Aron is constantly on the back foot, unsure about his place in the world and sensitive to receive the good will that his fellow Gentile Danes take for granted. Even his financial success is a source of potential shame, and he aspires to be taken seriously as an artist, author, and thinker.

Aron is particularly susceptible to the opinions and advice of P. L. Møller. Peter Ludvig (no relation to Søren's old teacher Poul Martin Møller) is an award-winning poet with academic ambitions. He is a friend and early defender of Hans Christian Andersen and a political supporter of Grundtvig's radical Danish nationalism. He is also a notorious womaniser in a city that likes to be titillated by talk of seduction more than it likes actually doing it. In short, Møller is a bad boy with insider privileges. He represents many of the things that Aron both fears and aspires to. No wonder Aron will later devote the main part of his autobiography to Møller, describing him as “

looming up

” in Aron's young life like a sort of “nemesis.”

P. L. Møller first sought out Aron Goldschmidt on the strength of the latter's involvement with the

Corsair

. As the editor of the country's most feared satirical magazine, Aron is a powerful man. He founded the weekly periodical in 1840 as an outlet for radical ideas in opposition to both the conservatism and liberalism of the day. In the first issue, under a pseudonym, Aron wrote that people might object to a newspaper named after a type of pirate ship. Instead, the paper loftily claimed for itself that it was a vessel “

manned by courageous young men

[who] are determined to fight under their own banner for right, loyalty and honour.” The paper never did quite reach these heady heights, however, and soon gained a reputation for censor-baiting character assassination, gossip mongering, and attacks on the great and the good of Danish society, all the while hiding behind a wall of anonymity and secret identities. There was a serious edge to the paper, which had to constantly dodge official censorship by instituting a rotation of straw-man editors who would take the fall if things got really bad. In one instance in 1842 Aron ran out of fake editors and had to face the law himself. He was sentenced to “

six times four days

” in jail as a result. The events only served to strengthen Goldschmidt's resolve, and the

Corsair

continued its reign of terror unabated. When Møller came on board he joined a small team of writers contributing to a paper read by everyone, high and low, but

admitted by none. Hans Christian Andersen noted about the magazine that the elite wouldn't stoop to buying such a rag, but they would “

read to pieces

” their servants' copies.

On its best days the

Corsair

shows flashes of brilliance, but even Aron knows it is not the ideal vehicle for his skills. Aron has not forgotten his more serious literary and political ambitions. One day in 1844, following an unsatisfying showing at a political event where he and his people were sidelined yet again, Aron shares with Møller his frustrations at being Jewish in Denmark. Møller's advice is direct and to the point. “

With feelings

like that,” he says, “one writes a novel.”

A Jew

came out in 1845. It was ascribed to the pseudonym Adolf Meyer, but following Copenhagen literary culture, the people who mattered knew Aron Goldschmidt was the source. The novel, recounting the trials and tribulations of a Jewish man in Denmark, is widely praised. Amongst its admirers is Søren Kierkegaard.

Søren had long taken an interest in Aron, who was a few years junior to him. The two had met at one of Mrs. Rørdam's parties, and their relationship developed on the streets where Søren would offer unsolicited advice on everything from Aron's literary output through to his choices in clothing. On one occasion Aron had stepped out in a particularly garish coat, only to be discreetly taken aside by Søren and given some frank advice. “

You are not a riding instructor

. One ought to dress like other people.” At the time Aron was mortified, but also grateful for the paternal attention. On another memorable occasion in 1841 Aron had arranged for the

Corsair

to print a stilted but favourable review of Søren's

On the Concept of Irony

. It was the first time Søren was mentioned by the paper, and he was not overly thrilled. The

Corsair

was generally more suited to caricature and satire, and Søren gently took Aron to task for the clumsy article, encouraging him instead to focus on perfecting his skills at “

comic composition

.” The advice was kindly delivered, and Aron was initially flattered by the attention. Yet as with the frock coat, the feedback was also a source of humiliation.

Now, four years later, Aron enjoys an influential position as an editor of his own paper. He is well remunerated. His novel

A Jew

is well received and widely praised. It has been translated into foreign languages, including English. Søren can boast none of these accolades. Yet here is the Master, once again taking Aron's arm, indicating another seriousâand probably condescendingâconversation is about to commence. It's all very confusingâhelpful and infuriating at the same time.

“

Which of your book's characters

do you think was the best delineated?” asks Kierkegaard.

“The hero,” replies Aron immediately.

“No,” says Søren, swinging his cane, “it is the mother.”

Aron is surprised. “I hadn't even thought about her at all in writing the book.”

“Ah, I thought so!” says Søren, delighted.

Søren then asks Aron whether he has read all the positive reviews his book is getting in the Danish press. “What do you think the point of it is?”

Aron has read them, and he is gratified, but he assumes the kind words are “quite simply intended to praise the book.”

“No,” Kierkegaard interrupts, “the point is that there are people who want to see you as the author of

A Jew

, but not as the editor of the

Corsair

. The

Corsair

is P. L. Møller.”

When Aron hears this, he knows the game is about to change. For a while now, P. L. Møller has been angling for a serious position in the university and aspires to a professorship in aesthetics. If his name is openly associated with the scurrilous and populist newspaper it will ruin his reputation. Møller is a large (even “looming”) figure at the

Corsair

, but it is still Aron who is the proprietary editor, a fact of which he earnestly reminds Søren, but to no avail. Upon hearing about the conversation back in Aron's office, Møller panics. Is his cover blown according to general opinion, or is this just another one of Søren's private schemes?

The answer is a bit of both. Unbeknownst to Aron, Søren has taken

him on as a sort of paternalistic project. He describes Aron in his journal as “

a bright fellow

, without an idea, without scholarship, without a point of view, without self-control, but not without a certain talent and a desperate aesthetic power.” He thinks that Aron's talents are wasted on the

Corsair

. Søren has no regard whatsoever for Møller, who was likely the model for the perfidious “Johannes the Seducer” character in

Either/Or

. Søren clearly thinks Møller is a bad influence on the pliable Goldschmidt. He writes in his journal that it is his goal to separate Goldschmidt from Møller and to take him from the

Corsair

. “

It was my desire

to snatch, if possible, a talented man from being an instrument of rabble-barbarism.”

The conversation with Aron was Søren's first shot across the

Corsair

's bow. Søren saw the paper as a blight on society, its form of irresponsible and unethical satire a source of “

irreparable harm

.” Yet Søren's designs to sink the pirate ship while rescuing its captain are not wholly disinterested. As always, he has his own authorship and its reception in mind too.

Søren had an odd relationship to his critics and reading public. In private conversation and in his journals he fretted and obsessed over every review his books received, and he clearly valued the good opinion even of his adversaries. In the public forum, however, Søren actively repelled attention and tended to avoid being drawn into wider conversations about his books. Not that all his books received the same attention. As a general rule the earliest tomes such as

Either/Or

got more discussion than the later ones, probably due to (understandable) reader-fatigue at the ever-increasing complexity of the authorship. The salacious material in “The Seducer's Diary” in

Either/Or

did not hurt either. Heiberg was muted and patronising in his praise of

Either/Or

, describing the “Seducer's Diary” in particular as “

disgusting

, nauseating and revolting,” a designation he meant as a reproach but which tended to attract more readers than it repelled. Søren was affronted by Heiberg's review, prompting Victor Eremita to write an equally sarcastic and patronising “thank you” to the literary doyen in the

Fatherland

four days later. Other negative reviews could expect to receive similar

dismissive (pseudonymous) responses. Not all the reception was negative, of course. In fact, the reviewers were often fulsome in their praise. Bishop Mynster (under the pseudonym “Kts”) wrote a good review of

Edifying Discourses

.

Fear and Trembling

and

Philosophical Fragments

got some good notices. To Kierkegaard's frustration, however, even the positive reviewers were plodding and didactic in their understanding of the works. “

No, thank you

, may I ask to be abused instead,” he complained in his journal of one enthusiast, “being abused does not essentially harm the book, but to be praised in this way is to be annihilated.” Other positive reviews got even shorter shrift, with Kierkegaard (or a pseudonym) going out of his way to alienate potential fans. A glowing write-up in the

newspaper

Berlingske Tidende

(“Berling's Times”), which too closely identified Kierkegaard with the pseudonyms, prompted Søren to write indignantly in the rival paper

Fatherland

. The

Times

, he sniffs, is fit only for wrapping one's sandwiches! This was all perfectly in keeping with the campaign of indirect communication. After all, if Søren had been trying to gather followers he would not have created such an elaborate cloud of pseudonyms.