Kierkegaard (2 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

Thanks to St. Mellitus College for providing the research leave during which I wrote this book. I love being with all the staff and students at St. Mellitus. It is a remarkable place. Special mention needs to go to Jane Williams, Lincoln Harvey, and Chris Tilling for personal support and practical advice. My busy colleagues Simone Odendaal and Hannah Kennedy read early versions of my opening chapter, and their feedback was much appreciated. I have been fortunate to study and sometimes teach Kierkegaard at McGill University in Montreal and the University of Oxford. I am grateful for the guidance, helpful opposition, and friendly support I received in these places, especially from George Pattison, Joel Rasmussen, Torrance Kirby, Douglas Farrow, Johannes Zachhuber, and Oliver O'Donovan. Elsbeth Wulf was my patient Danish language teacher and first window into Søren's Copenhagen. Conversations with fellow Kierkegaardians Matthew Kirkpatrick and Christopher Barnett helped form my thinking, as did Luke Tarassenko's timely reminder regarding Captain Kierk's changing sense of his role as a poet. Gordon Marino, Eileen Shimota, and the library staff provided help and advice during my time at the excellent Kierkegaard Library at St. Olaf's College in Minnesota. Thanks are also due to Bruce Kirmmse, to Elizabeth Rowbottom and Tom Perridge at Oxford University Press, and to Jon Stewart, editor of C. A. Reitzel's Danish Golden Age series and associate professor at Copenhagen University's Søren Kierkegaard Research Centre. I have very much enjoyed working with my editors Katya Covrett, Bob Hudson, and the team at Zondervan. My wife,

Clare, a historian of clothing and culture, was writing her book at the same time as I was mine. Her selfless sense of fun, patience, and interest during this time was a constant source of joy and a model for me to imitate. Thanks to my father, Norman, and my mother, Vaila. His enthusiasm has given me much encouragement, and her keen reader's eye has provided invaluable editorial suggestions, and it is to them this book is dedicated.

A Controversial Life

The new bishop stands at the window, looking at the crowd milling in the courtyard below. He cranes his neck, trying to get a better view of the church door opposite, but it is difficult. He cannot see, but at the same time he does not want to be seen. That would never do. The bishop has pushed himself to the limits of his reputation to avoid any connection to the distasteful funeral going on across the way. Yet he knows, along with all of Copenhagen, that the events below are all anyone is talking about. They will be in all the papers tomorrow, and the next day, and the next. It is of paramount importance that these papers record that the newly minted Bishop of all Denmark, Hans L. Martensen, shepherd to the nation, was not present at the burial of his former student, now the scourge of all Christendom, Søren Kierkegaard.

Martensen had good reason to expect heightened public interest. All of Denmark's respectable papers, as well as her less respectable (but more popular) magazines had been providing a steady drip of comment on the events leading up to, and following, Søren's passing. The details of his life, after all, were irresistible to any journalist worthy of the name.

An enigmatic, brilliant loner with more than a whiff of scandal about him, Søren Kierkegaard had long enjoyed the reputation as something of a dangerous dandy about town. Every literate citizen, and more than a few who did not read at all, had an opinion. Sophisticated, artistic citizens recognized his talent, even if they did not actually understand his books. He was the kind of author who it was important either to be seen to be reading or to pointedly ignore. Morally upright citizens admitted he was a good writer, but was he a good man? The constant trips to the theatre and the flagrant gallivanting about town with all sorts suggested an absence of moral fibre. And didn't Søren despise his brother Peter Christian, and didn't he refuse his brother to even attend at his deathbed? In any case, Peter, so earnest and plodding, almost certainly hated his brilliant and infamous younger sibling. Religious citizens remembered him as the promising theologian who spoke and wrote endlessly about Christianity and yet who did not become a pastor and now never even went to church. Romantic citizens vaguely suspected this stillborn church career was somehow connected to the scandal of his broken engagement years before. “Such a sweet young girl,” they would whisper to each other,

“and taken off by her new husband to the West Indies! It's almost like they were escaping something, or

someone.

” Older citizens of Copenhagen could shake their heads and say they always knew Søren would come to a bad end. There was something not quite right about his father, Michael. He was a miserable old miser. And the timing of Michael's second marriage, to Søren's mother, so soon after the death of his first wife was positively scandalous. And she was the maid! Younger citizens knew him from the caricatures and cartoons the satirical magazine the

Corsair

was always churning out

.

A magazine that they would hastily sneak a peek at when their more respectable elders were not looking. These respectable citizens knew him as the one the King of Denmark had marked out for special favour. Less respectable citizens either knew of Søren as the one who stopped to talk to them on his walks about town or as the one they threw stones at as he passed. Student citizens knew that his first name, when attached to a character in a comedy revue, would automatically get laughs. For the same reason pregnant citizens took this name off their list of potential baby names. The novelists of Denmark's Golden Age, including Hans Christian Andersen, anticipated and yet dreaded Søren's reviews of their latest works. Poets and playwrights admired the man who wrote provocative fiction. Philosophers read him for his statements on the nature of time, existence, and the meaning of life. Conservatives liked Søren for his opposition to democracy and revolution. Liberals liked Søren for his championing of the individual and the common man against the forces of inherited tradition. Atheists loved his attacks on the clergy and official religion of Christendom. Reformers, longing for a renewal of Christianity in the land, also loved his attacks on the clergy and official religion of Christendom. Clearly, this was a man of sharp contradictions and puzzling paradoxes. But all the citizens agreed that he was rich. Wasn't he rich? He must be rich. To whom will he leave all his money?

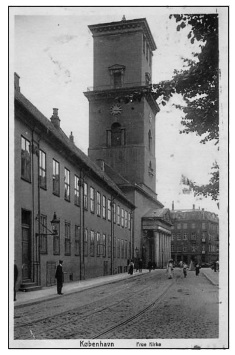

The Church of Our Lady, Copenhagen's “mother church” and the Kierkegaard family's place of worship. Martensen lived just across from the front portico and Søren lived about a five-minutes' walk down the road.

So it is that when on Friday, November 16, 1855, Denmark's most venerable newspaper announced: “

On the evening of Sunday

, the eleventh of this month, after an illness of six weeks, Dr Søren Aabye

Kierkegaard was taken from this earthly life, in his forty-third year, by a calm death, which hereby is sorrowfully announced on his own behalf of the rest of the family by his brother / P. Chr. Kierkegaard,” it did so with the full knowledge that enclosed in these simple lines raged a storm that threatened to spill out onto the quiet streets of Copenhagen and beyond. Or so they must have hoped. All these citizens had to get and share their opinions somewhere, after all. It was a good time to be a journalist.

Old Copenhagen

If the editors who wrote the bare outlines of the story did hope for someone else to provide the colour commentary, they were not disappointed. Other public figures were not reticent to opine on Søren's passing. Writing in the periodical

North and South

, an editor and journalist (and himself not without literary ambitions), Aron Goldschmidt spoke up for many of Kierkegaard's admirers: “

He was without a doubt

one of the greatest intellects Denmark has produced, but he died a timely death because his most recent activities had begun to gain him precisely

the sort of popularity that he could never have harmonized with his personality. The most dangerous part of his actions against the clergy and the official church is now only just beginning, because his fate undeniably has something of the martyr about it.”

The Jewish Goldschmidt was writing outside the walls of the established church. Key figures of Danish Christianity were less distraught about Søren's passing, and more certain about his status as a Christian hero. Namelyâhe was nothing of the kind. The celebrated Pastor Nicolai Grundtvig, a cultural and ecclesial giant in Danish life then (and now), also spoke for many when he preached a sermon on the day of Kierkegaard's burial, giving thanks that one of the icicles hanging from the church roof had now melted and fallen off. In a letter to a friend, Grundtvig said of Kierkegaard, “

I do not wonder

that he was surprised by death, for as long as the day of the Antichrist has not yet come, those who tinker with [the national church] will always come to grief, and quickly, just like false Messiahs.”

To be labelled a great intellect, martyr, and false messiah all at once was no mean feat, but it was not only the religious and literary establishments that had their points of view. The scientific fraternity also made its voice heard. Kierkegaard was, evidently, a medical marvel according to a group of research students who complained about the decision to bury Søren. He should, they said, have been given an autopsy instead of a traditional burial. A mighty brain like Søren's deserved to be preserved for science. That the engine which powered such a literary output and such a quirky personality should moulder in the ground like any common man was a travesty to research. They complained to the hospital, but the hospital acquiesced to the wishes of the family. This was much to the relief of one of Søren's friends who had been present at the petition and who wrote in his memoirs, “

I thought it decent

of the hospital, but those who were enthusiasts of science did not think that sort of thing should be taken into consideration.” Decency won out, but speculation over the contents of Kierkegaard's skull remained. “

He was said to suffer

from a

softness of the brain,” wrote one of Søren's committed enemies. “Was this responsible for his writings, or were the writings responsible for it?”

Here was the rub. It was Søren's writings, especially the writings which made up the final stage of his life and career, which lay at the root of all the fuss. This collection of pamphlets and newspaper articles are now known collectively as Kierkegaard's “attack upon Christendom,” and it was while engaged in this attack that Søren died. It was precisely because of these writings that Søren's admirers and enemies alike agreed that he absolutely should not be laid to rest in a traditional manner. And it was precisely because of these writings that many of Søren's family desperately wished that he would.

Henriette Lund, Søren's niece, provided many remarkable eyewitness accounts of her famous uncle. In her later life she jealously protected his reputation.

Søren had said he wanted to upset blind habits and overturn easy assumptions. In this, if nothing else, he had succeeded. His niece, Henriette Lund, was present at the house following her uncle's death. She paints a picture of a family torn between private grief and public responsibility. No one was thinking clearly about the future but were, she says, “

living minute by minute

in the present.” As a result, no one made definite arrangements for the funeral, and each was leaving the decisions up to the others. There had to be a funeral. But when and where should it take place? If it took place quietly, then it would look like the family was ashamed of Søren and his life's work, which was all anyone was talking about at the time anyway. On the other hand, as Søren's nephew (and younger half-brother to Henriette) Troels Frederik notes in his memoirs, a traditional church funeral would have struck a “

strongly discordant

” note. Troels summarized the quandary well: “

Everyone knew

that the deceased had characterized pastors as liars, deceivers, perjurers; quite literally, without exception, not one honest pastor.”