Kiss and Make-Up (2 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

Somehow, through all the craziness with women, despite the sheer numbers, I managed to become a dedicated father. If this seems strange to you, think of how it seems to me. My father left my mother and me when I was still young, and I grew up convinced that I would never have children, in part because I remembered the pain of abandonment, in part because I lived in terror of repeating my father’s mistakes. Then I met a girl named Shannon Tweed. The next thing I knew, I was holding my son in the hospital, unwilling to give him up to the doctors. How do I reconcile the cocksman with the family man? The same way I reconcile the shy immigrant boy with the leather-and-studs Demon who climbed onstage to breathe fire. Every personality has contradictions, and a large personality has large contradictions.

I have lived my life for myself. I’m not afraid to admit that. But I have also lived my life for the fans: for the faithful soldiers in the KISS Army, those who stood by us through thick and thin, through changing fashion, those who braved bad traffic and bad weather to come out and let us entertain them. When I first sat down to write this book, I was torn by whether I should tell the truth about their

band: about the internal rifts and feuds, the personality conflicts and personality disorders. I was torn because I feared that the truth might ruin people’s perception of their heroes. And whatever else KISS was, it was about heroes, about magic, about believing in it and delivering the goods. You, the fans, have always deserved the best from us. It’s one of the reasons we introduced ourselves at every show with “You wanted the best, you got the best. The hottest band in the world, KISS.” In sickness and in health, whether we felt like it or not, we believed we had an obligation to get out there, play our hearts out, and give you everything we had.

I believe that when children grow up, they should find out the truth about their parents. Those of you who believe in KISS need to know the truth. I know that a lot of the things you’ll read in this book will be hard to take. I know that some fans may get upset at me. I know that some members of the band will hate me more than ever and claim that everything between these covers is a lie, despite my memory, despite the documentation, despite the witnesses who will attest to the events.

Either way, here’s the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help me God.

I was born

August 25, 1949, in a hospital in Haifa, Israel, overlooking the Mediterranean. At birth, I was named Chaim Witz: Chaim is a Hebrew word that means “life,” and Witz was my father’s last name. Just a year earlier, Israel had become independent after roughly 100 million Arabs tried to prevent Israel from appearing on the world map.

The war for Israel’s independence followed in the wake of an earlier war, World War II, and the terrible plan of the German Nazis to erase Jews from Europe and eventually from the world. My mother’s parents were Hungarian Jews, and my mother had grown up in Hungary during the 1920s and 1930s. When my mother was fourteen, she was sent to the concentration camps, where she saw most of her family wiped out in the gas chambers. While in the camps, she ended up doing the hair of the commandant’s wife, so she was shielded from many of the horrors that befell the other Jews. Having survived that horrific time, after the war she went to Israel. I think the survival instinct was so strong among that generation that, after leaving the camps, they couldn’t imagine failing at anything else, and so they set out for this strange new land.

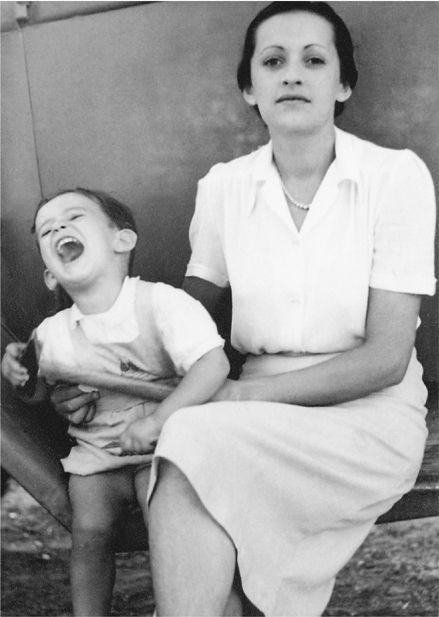

I was posing with my mother and a hammer—for some reason I loved hammers.

Israel was a new country, only a year older than I was, and its existence was still very much in question. But I was unaware of all that. It was always such a part of my daily routine that I wasn’t able to separate it from any other aspect of my experience. For example, I remember that my dad, Yechiel (or Feri) Witz—who was physically imposing, at least six foot five—would come in on the weekends with his machine gun and put it on the kitchen table. The front lines were fifty miles away, and everybody, every male and most females, was in the army. There were no exemptions. If you lived there, you were in the army.

We were poor, but I was chilly, so my mother sewed me this coat from the blanket I slept in. I was chewing on a pretzel here at age two.

The gun on the table was one of the few things I remember about my father, because he wasn’t around very much. I do recall that he was this large, powerful being with a large, powerful presence. One vivid memory does stand out. Once there was a mouse in the house, and it ran across the room and under the couch, and I remember my dad picking up the couch and holding it up on one side with one arm while he was trying to shoo the mouse away with the other. I couldn’t believe it. A man lifting up a couch? This was like nothing I had ever seen before. It seemed impossible.

Chaim, Flora, and Feri Witz.

I had polio when I was a very young child, probably when I was about three years old. Apparently, I lost most of my muscle control from the waist down. The doctors were worried that it would get worse and sent me to the hospital. In the hospital, I was kept off the ward, in isolation, and when my mother and father came by, they had to communicate with me through a closed window. For some reason, even at that young age, I had a strong sense of what was proper and what was improper, and I knew that it was improper to go to the bathroom in your own bed. My mother potty-trained me early on. She showed me the toilet and explained what it was for. At that time, there were no diapers in Israel, and I learned quickly that the bed was for sleeping, and the bathroom was for your other business. It was very clear. In the hospital, in the ward, I needed to get out of the bed and use the bathroom. I complained and cried and complained some more. I knew I needed to get to the bathroom. I knew that any other solution to that problem was the wrong solution. But the nurse didn’t come, and somehow I managed to pull myself over the baby crib and did my business on the floor, while I hung on to the side of the crib. Then the nurse came. She wasn’t around when I was in trouble, but the minute there was poop on the floor, she came right by, and she started yelling at me, wondering why I had gone right outside the crib. And my mother stormed right in and screamed at her for not being there for me. “What did you expect him to do?” she said. “Go in his own bed? He’s a good boy. He knows better.” In her eyes, I could do no wrong.

I was always a loner, even though I had friends. I spent time by myself, observing things, organizing the world around me in my own mind. For example, I was fascinated with beetles. In Israel, they had these huge Old Testament beetles. The beetles here in America are nothing compared to them. These Israeli beetles were the size of small dinosaurs, maybe two inches long. They were brightly colored and beautiful. They looked like jewels. And I used to tie sewing thread around the neck of these beetles and put them

in matchboxes along with a little bit of sugar. The beetles would live there until I opened up the box, and then they would fly around, still tied to my thread.

As I got older, I became less of a loner. Instead, I became more interested in showing off around other kids and getting attention. So I changed from the kind of kid who would be a falconer for beetles, letting them fly around at the end of a leash of thread, to the kind of kid who would put a beetle in his mouth and let it walk around in there. Other kids were amazed by that. They thought it was disgusting and brave. Most important, they couldn’t look away.

Though I was born in Haifa, my family lived in a place nearby, a little village called Tirat Hacarmel, which is named for the original biblical Mount Carmel. And I remember as a kid climbing that mountain, which is more of a hill, really, rolling hills, similar to southern California’s hills. I remember going up the hill and picking cactus fruit when I was a kid, then climbing back down and selling the fruit at the bus depot for half a

pruta

, which is basically half a penny. (Cactus fruit are sweet and juicy on the inside, but have spikes on the outside. Their Hebrew name is

sabra

, and that’s what Israelis are called, because they, too, are prickly on the outside and sweet on the inside.)

Living in Israel among all the other

sabras

was strange, especially in school, because Israeli classrooms taught this quirky mix of history, religion, and politics. Think of it: in class, we were taught about an old book called the Bible and were told that the events recounted in this book—incredible events, really—actually took place in the country where we were living. It was a strange notion to swallow and to understand. Because here was a whole book that talked about the creation of life, and Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and the flood and the Exodus. And then we were told, “This is where it happened. You’re living in the place.” It was pretty heavy stuff.

At the same time, I wasn’t really all that conscious of being Jewish in Israel, because almost everyone was the same as I was in that respect. Clearly there were Arabs walking down the street, and there were some Christians, but I was oblivious to all that. I was not aware of anything except being Israeli. You’d think that my mother,

having just come through the war and the concentration camps, would have been consumed with what had happened to her, but she wasn’t. It was too painful for her to talk about. She never discussed the camps and rarely talked about her childhood in Hungary. All she ever talked about, and only every once in a great while, was that the world is a big place, and there are some good people and some bad people. To this day, I am amazed that she had that self-control. It’s proof that my mother, ethically, morally, and in all other ways, is a much better person than I will ever be. She had at that time, and still has, an abiding trust in humanity. She still believed the world is a good place, and that goodness prevails over evil more often than not. I don’t know that I would have had that point of view if I had lived through what she had.