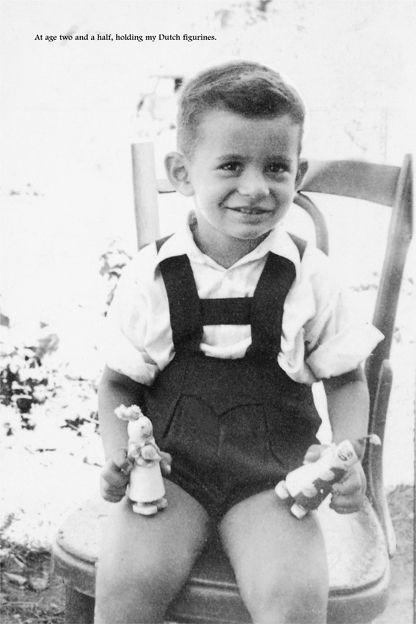

Kiss and Make-Up (3 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

When you’re a kid, you don’t know that people are different races, different ethnicities, different religions. The one thing I did notice about my neighborhood was that it was filled with different languages. Some of the Jews in Israel spoke Hebrew. Some spoke Yiddish, which is a European language that combines Hebrew and German. In my house, the most important language was Hungarian, because my mother didn’t really speak Hebrew all that well. And then later, when my mother went to work, it was Turkish and then Spanish, because my baby-sitter was Turkish and the next-door neighbors were Spanish. At an early age I was able to speak Hebrew, Hungarian, Turkish, and Spanish.

I was not aware of America or the rest of the world. But I do remember my mother taking me to a movie. I must have been four. It was my first experience with non-reality-based images. I had never seen a television set, and I had heard radio only occasionally. We went to the movie, but we couldn’t afford to go inside, so my mother held me in her lap outside of the theater, and we watched the movie, which was shown on a big screen without a roof. It was amazing. I was transfixed. Later, I remembered that it was

Broken Arrow

, with Jimmy Stewart and Jeff Chandler. But at the time, all I could see were huge images of cowboys and Indians and a mythical Wild West where there were outlaws and heroes. Cowboys were the first superheroes, as far as I was concerned, the first characters who were larger than life and more powerful than ordinary people. As important as all of this became to me later—the concept of heroes, and the magic of the movies—what made the greatest impression on me was the sound of American English. That might have been the first time I heard English, and it sounded funny to me. It was one of the languages that, as a kid in Israel, we mimicked. To my ears, the American language had its own sound, with lots of y’s, and lots of soft r’s. These sounds didn’t exist in Hebrew. That was my fake English, and it sounded pleasant to me.

From the beginning, it seemed, my father and mother would separate. A simple conflict lay at the heart of my parents’ bad marriage. My mother, Flora, was extremely beautiful as a young woman. She had classic movie star looks, like Ava Gardner. In the village where they came from in Europe—Jand, Hungary—she was considered quite a catch, but not as big a catch as my father. He was highly valued because he was the tallest in the village, probably six-five or six-six, although I remember him as even bigger. In my memory he was six-nine, a giant. Though his name is Yechiel in Hebrew, he was called Feri in Hungarian. When they met and married, they were young, in their early twenties, and during the first few years of their marriage, my mother gradually woke up to the idea that my father wasn’t going to be the kind of provider she needed. For some reason, he could never make ends meet. He could never run a business successfully. He was not really a pragmatist. He was more of a dreamer. And for a carpenter, being a dreamer was roughly equivalent to being unemployed. He would make pieces of furniture that he loved

but nobody else liked, and he would find to his surprise that he couldn’t sell them. But it was more important to him to do what he wanted to do. And I remember he whittled me a scooter with his own two hands. Not an electric scooter, but the push kind, the ones with wheels and a little platform. He made it for me for my birthday. It was always impressive to see what he could make, and I’m sure that my mother was happy that he got off on his own creativity, but at some point you have to begin to submit to practical needs as well: namely, how do you make money? He didn’t know the answer, and she kept asking the question, and they fought all the time.

Even if we had been living in a secure country, with a secure middle class, they probably still would have fought, but we were at the edge of this new frontier, in this new country, with new neighbors, new languages, and new rules. So my mother’s anxiety about these issues intensified. Whether because of her pressure or my father’s own self-esteem issues, their arguments would sometimes devolve to physical violence. Not terrible beatings, and not one-sided either: I remember that every once in a while one of them would push the other. At one point—I must have been four or so—they were bickering back and forth, and I jumped on my father’s leg and started biting him near his knee. I can’t even say for certain that it was a serious fight, but I was just trying to protect my mother.

Things didn’t get better, and the fact that they weren’t getting better made things worse. My father left Haifa for Tel Aviv, to look for work and take some time away from my mother. When he was gone, my mother started working at a coffeehouse called Café Nitza. I’ll never forget it, because when you pulled up to it, you saw a kind of Mama Beulah figure, a large, fat, happy black woman sipping coffee. Up until that point, I think, I’d never seen a black face of any kind. She was so big and so happy, that face on the sign. I remember as a kid going to see my mother and getting my first cup of coffee and a poppyseed cake. I remember being hit by the caffeine, and I thought I was going to pass out. I couldn’t believe what was happening to me. Everything started moving at a different speed; in my mind, I thought I was slurring my words.

My mother liked working. It gave her self-esteem, and she was

very disciplined and a very hard worker. But still she wanted to make her marriage work. One day she told me that we were going to see my dad. So we took a trip to Tel Aviv, and we searched in vain for him for a little while. He wasn’t where he was supposed to be. He wasn’t in any of the places my mother expected to find him. So we went to the movies. I don’t know if my mother suspected he might be there. I don’t know if she was just going to relax for a little while. But in the lobby, I caught sight of my father. He was at the top of the stairs with a blond woman. I turned to my mother and told her, “There’s Dad with a blond woman.” At the time, I didn’t think of it in terms of jealousy. That didn’t enter into it at all. It was more like a game, looking for my father, and I had won the game by spotting him at the top of the stairs with this blond woman. My mother knew differently. We went to his apartment, and somehow she got a passkey, and we went inside, and she went through his pockets and found condoms in one of them. We went back to Haifa, and the two of us continued with our lives, and that was the last of my father’s role. He didn’t surface again. I have no idea whether my mother tried to make contact privately, and she won’t talk about it to this day. For me, as a child, that was the end of that. The last visual image that I had of my dad was at the top of the stairs with that other woman.

I looked up to my father—he was everything I admired.

After that, it was just the two of us, my mother and me, and she devoted herself to raising me. She went out on a date or two with some guys and would always do her best to explain to me what was happening. I didn’t react very well, probably because I thought that I would lose her affections to somebody else. I became jealous and guarded, and I let her know in no uncertain terms that nobody else was permitted in the arrangement. One way or another, it worked, because my mother stayed single until I was about eighteen or nineteen.

Shortly after my mother and father separated for good, my mother and I moved from Tirat Hacarmel to Vade Jamal, another village in the Haifa area. At that time, I was five or six and starting to get a sense of the kind of country I was living in. For starters, it was a poor country that was just finding its way. Israel worked on a food-stamp system, and you could have meat once a week. Even milk wasn’t something you could just go and buy. You had to get your stamp. There were certain amenities we simply didn’t have. I never saw toilet paper or tissues. We wiped with rags. They were washed. Showers were unheard of. I bathed in a metallic bathtub, and my mother would heat the water up on the stove and then pour it into the bathtub, pot by pot, until it filled up.

Despite that, I was mostly oblivious of the idea of rich or poor. There were bullet holes all over the walls in the apartment where we lived, because three years earlier the Arabs and the Jews were fighting the War of Independence in the streets. But I was oblivious to the bullet holes. It just looked like a building. I do remember one incident: every once in a while my mother would save up money to bake a

babka

, which is a thick pastry. When she made the frosting

to cover the cake, she would let me stick my finger in the pot and taste it. I remember being horrified that there was a big hole in the middle of the pot. And I was embarrassed to say anything to my mother at the time, because I thought she would feel embarrassed herself. But when I did happen to mention it, she started laughing, because in fact, the

babka

pot that you cook in actually has that big hole in the middle. To me, though, it was just a broken pot, and a sign of our poverty.

I was my mother’s only child. There were no other children, no husband. As a result, she protected me fiercely. We were a team, and she was intent both on raising me right and on ensuring that other people treated me with respect. Some of my most vivid memories are of my mother defending me, which she did passionately. I guess it was her way of announcing to the world that she valued her son and expected the same from everyone else.