Kiss and Make-Up (4 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

My mother used to have these huge thigh-high boots, the kind that plumbers wear, as opposed to the stylish boots that are more familiar to Americans. They were very clunky, and I remember watching those boots go through the dirt as I walked along behind her. One day walking along behind those boots, I saw a neighborhood boy who had a bad habit of throwing rocks. Or more to the point, he had a bad habit of throwing rocks at me. I was minding my own business, and suddenly a rock hit me in the head. My mother moved faster than I had ever seen her move. She chased down this kid and picked him up off the ground by his hand and smacked him so hard that he was swinging like a sack of potatoes. This kid was crying, but she couldn’t, or wouldn’t, stop hitting him. She just kept slapping him. Then she took me by the hand in front of his parents, as if to say, “Yeah, what are you going to do about it?” Nothing came of it. We walked away.

Another time my mother’s protectiveness actually landed us in the police station. This was slightly later, after I had started school in Vade Jamal, and after I had established myself as the loud kid, the show-off: the kid who always had to go the farthest, the highest, the

fastest. There was a fig tree that grew over into the school grounds, although it was rooted in the yard of the woman who lived next door. The kids loved to climb up the part of the tree that was in the schoolyard, then climb down into the neighbor’s yard. When she came out, all the kids would clamber down and scurry away. I was usually the last one down, because I was in the highest branches. One time I was too slow coming down, and the woman caught me. She had a banana stalk in her hand, and she started hitting me with it. I don’t remember how badly she hurt me, only that I was scared and that she knocked the wind out of me. My friends brought me home after school and told my mother about the beating, in front of me.

The next thing I knew, we were back in the street again, and I was behind my mother and her boots, and we were going to the woman’s house. We got to the house, and my mother banged on the door, and the woman came out. I remember being struck by her size. She was big, bigger than my mother, and had a hard look. She must have had a hard life. My mother asked just two questions. The first one was “Did you hit my son?” The woman said, “Yeah, he climbed my tree, and anybody that does that is trying to steal my figs, and I will hit anybody that I see.” The second question was “What did you hit him with?” My mother spoke levelly, as if she were just trying to collect information. The woman said, “I’ll show you what I hit him with.” She brought out the banana stalk.

My mother grabbed the stalk out of the woman’s hands and started beating her over the head with it. At first, Mom was swinging it with one hand, and then she had it two-handed, as if she were playing baseball, and she was bringing it down on the woman’s head, hard, the way you do with a sledgehammer over a spike. This woman was being drilled into the ground. The woman’s legs gave way, and she was on her butt against the doorway, but even then my mother kept banging her over the head. By the time my mother got through with this woman, I was just amazed, because I’d never seen blood literally spray out of a person’s head like a sprinkler system. It was just spouting out. It looked almost comical. There was blood everywhere. The woman was covered with blood, and my mother was covered with blood. It was hard to believe. It felt almost like a cheap horror movie.

My father at age forty-four.

In short order, because it was a small town, the police were there. There was a police station around the corner from the school. The cops took my mother and myself—we walked, because there were no cop cars—two blocks to the station. The sergeant behind the desk had a huge mustache; you couldn’t see his mouth, it just hung over his lips. “Did you—” he said to my mother, and before he could even finish, she nodded. “Yes,” she said. “Yes, I hit her over the head.” The sergeant asked her why, and she told the story and explained her thinking: whether her son was right or wrong, she said, no one was allowed to lay a hand on him. And then she got carried away, because it was emotional in the retelling, and she must have felt defiant, and she started to yell at the sergeant and told him, “If you even so much as look at my son in the wrong way, I’ll split your head open, too.” The sergeant repeated that with an expression of disbelief, and the rest of the cops started laughing. Then he let us go.

When I look back on Israel, I find that most of my memories are about my mother, or clothing, or food—the basics. I left when I was still a child, so my personality didn’t really come into its own there, but every once in a while a memory comes up that surprises me with its strength and explains something about myself. For many years, for example, I couldn’t stand the sight of spiders. I dimly remembered an incident from my childhood, but it wasn’t clear. Then it

came back to me: one morning my mother was getting ready to go to work, and I was getting ready to go to school, and she put my hat on my head. It didn’t quite fit—there was a lump in it. She took off the hat, saying something about how my hair must be crumpled underneath. While she was talking, the biggest spider I ever saw crawled out of the hat and ran away. I shrieked, and for years I couldn’t get over the idea that there were spiders waiting for me. I had a habit of looking under clothing and hats and in pockets to see if anything was crawling inside.

There’s a similar story with chickens. Across the street from us lived a Moroccan family who always treated me as one of their own. One of the daughters in that family was named Jonet. She was a little older than I was—she must have been twelve to my five or six. She would always treat me to these huge cucumber, butter, and bread sandwiches when I came over. That was how we did things then: you’d have your bread, and put on it a piece of vegetable and lots of butter, and that was your sandwich. It was great. I was always looking forward to spending time at her place.

Her family had this chicken, a royal chicken with red plumage, and I always used to give it crumbs from my pockets. As soon as the chicken saw me walking in, it would start clucking. I guess it figured that it was feeding time at the zoo. One day I walked into Jonet’s place expecting to get a sandwich. But she said she had to go, and she was pulling the chicken by a leash. It was fluttering its wings, and cluck, cluck, cluck, it wouldn’t go. She tried to force it, but it resisted. So I said, “Let me pick up the chicken, he likes me.” I reached for the chicken, but she said, “No, don’t do that, he’s going to peck your eyes out.” I ignored her and picked up this giant chicken, and it settled into my arms like a newborn baby. And we walked. I didn’t know where we were going, but I was brave enough to carry it. After a little while, though, the chicken started to weigh on me. It was probably five pounds. So I asked Jonet how far we were walking. “Very close,” she said. “It’s just up here around the corner.”

As we rounded the corner, a large man with an apron came and grabbed the chicken from my arms. He held it by the neck and

snapped it, then produced a knife and cut its head off. I saw the body of the chicken running around while the head was in the man’s hand. It was the most hideous thing I had ever seen. Because of this memory, I couldn’t eat chicken in any way, shape, or form. Especially if the head was connected, with the wings and all that. You’d think this would be a trauma that would pass, but until my mid-thirties, if I was going to eat chicken, it would have to be amorphous and not look like a chicken.

With all this, it was a good time. My needs were simple because they had to be. As long as I had jam and bread, I was happy. To this day, I find fancy food, like French pastries and baby carrots, disgusting. Give me a nice piece of cake, and I’m in heaven.

One day my

mother and I received a care package in the mail. Inside there were cans of food and a sweater. It was the first time I had ever seen canned goods. My mother explained to me that it had come from her uncle Joe and her brother, George Klein. This was the first I had ever heard of a brother. In fact, she had two brothers. In Hungary, before the war, they had gotten wind that something bad was on the way, so they had gone to New York City. I asked my mother why they were sending us things. As I said, I didn’t have any strong sense of privation. I didn’t feel poor. I had food and clothing. Then she opened up the cans, and I tasted my first canned peaches, which I thought were just astonishing. I went to her, with the peaches still in my mouth, and said, “Where did this come from?” She said, “America.”

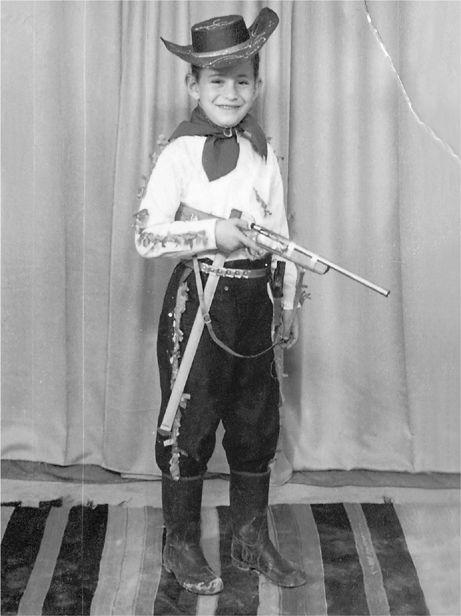

When I dressed up in this outfit, I felt like I really was a cowboy.

It wasn’t the first time I had heard that word, but it was the first time I could attach a concrete sensation to it—in this case, the peaches in my mouth. I remember thinking it was a funny-sounding name, partly because I was giving it the Hebrew pronunciation, with a hard

r.

I went around the house saying “Amerrrica” for days.

Pretty soon the word began to collect other associations. One of the first was cowboys. Once I recognized that America was the land of cowboys, that was enough to make me think more about it. I was eight and a half by then, and movies were bigger than the entire world, and a big part of movies was the cowboy myth. This was before rock and roll, before the Beatles. At that point, cowboys were the ultimate cool. They got the girl, they were the loners, they rode off into the sunset. And cowboys represented America, at least for all the kids who weren’t there. If you were a cowboy, you could exist in this pure heroic world. You could live by the gun. You were the judge and the jury, and you meted out justice with your hands. And you just moved on, and the girls loved you. You went off into the sunset.

In one school play, I dressed up as a cowboy, with a toy gun my mother bought me. It was the only costume that made sense. In fact, I was this small kid playing cowboy, with not an ounce of cool in me. But I was dreaming about cowboys, and through that, I was dreaming about America.

I don’t think I consciously understood it at all, but I would look up at the movie screen and see this other place where everything was just much more dramatic and much bigger. The thing about America that always came through loud and clear was its size.

The word was

big.

The people were big. The ideas were big. The women were big. Their breasts were big. The horses were big, and they had buffaloes there, which were big, and big trains. Everything was big. And for me, it was about to become a reality.

One day my mother told me to get dressed, because we were going to the airport. I had never seen an airport. I had never seen jets or planes or anything. So I was transfixed. Then as we started to walk down the tarmac, it occurred to me that maybe I should show a little interest in this process. So I said to my mother, “Where are we going?” And my mother said, “We’re just going one stop.” I thought we were going on a trip. So we got on the plane and stayed there. The trip seemed like an eternity—partly because it was a long flight, and partly because I was as sick as a dog. I had never felt so terrible before, not in my entire life. I just kept vomiting and vomiting. I must have thrown up everything I ate that morning, and everything from the day before and the day before that. Finally, we landed in Paris. I remember stopping in Paris only because my mother went out to the duty-free area to buy herself some perfume. Then we got back on the plane, and I was sick again, and finally we landed at LaGuardia Airport in New York.