Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death (24 page)

Read Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death Online

Authors: Katy Butler

Tags: #Non-Fiction

ing conditions that the Victorian-era nursing reformer Florence

Nightingale considered essential: quiet, rest, and fresh air. Of

those who suffer hospital delirium, 35 percent to 40 percent die

within a year.

My mother called me, weeping. She was exhausted. The

hospital was neglecting him. She was afraid to drive alone to

New Haven. She didn’t know what to do. She needed a driver.

She needed a medical advocate. She needed me.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 147

1/31/13 12:27 PM

148

katy butler

A Korean folk saying holds that after three years of caregiv-

ing, filial devotion disappears. I was lying on the couch worn

out when I got her call, looking up at the skylight. It had been

five years of back-and-forth flights, three of them in the previ-

ous eight months. Brian and I were packing for a nonrefund-

able week at a rented cabin in the mountains. I did not know

how many more years my father would last, and after that—

what then? My mother’s mother had lived to be ninety-two. My

mother might well live as long, which meant I’d be taking care of

her when I was seventy. And after that—how many years would

it be before Brian, whom I’d so far resisted marrying for reasons

I didn’t fully understand, needed my care? Who would be left

in the end to care for me? And why did most of the burden fall

on women? I called my brothers. It was their turn, I said. After

completing a weeklong acting workshop that he’d already paid

for, my brother Michael flew out. It was only his second visit

home since my father’s stroke.

Much to my relief, the doctors at Yale—New Haven decided

not to operate—a wise, “less is more” decision for which the

hospital paid a financial price. Out of $22,034 in services pro-

vided and billed, Medicare reimbursed the hospital only $6,668

under its lump-sum system—a figure that would have been far

higher, of course, if doctors had subjected my father to brain sur-

gery. All in all, the six-day hospitalization cost Medicare about

$16,891, including $8,723 for emergency, diagnostic, and doc-

tors’ services at Middlesex Memorial the first day and $1,500

for separately-billed doctors’ services at Yale—New Haven.

My mother insisted on bringing my father home as soon as she

could. He never returned to his previous “normal.” One morning,

while sitting on the couch, he asked my brother Michael why

the room was filling up with leaves. In hindsight, he’d have been

better off after his fall if my mother had not called 911 but just

washed the blood off his face and put him to bed.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 148

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

149

*

*

*

If my parents’ seventies were golden years, their eighties were

years of lead. For the first two years after his stroke—2002 and

2003—my father and mother organized their lives around their

hope of his getting better, her determination to help him, and his

fierce motivation to regain the ability to write and speak. When

hope of true recovery ended, they marched on, my mother grow-

ing ever more lonely and exhausted, and my father accepting a

constricted life of limited but real pleasures. The fourth and fifth

poststroke years—2005 and 2006—took those pleasures from

him. His sight dimmed so much that he could no longer read

the

New York Times

. His balance became so unsteady that my

mother no longer let him walk on his own and held him up by his

belt when he walked up or down stairs. He became bowel and

bladder incontinent, and that meant the end of his water walking

at the Wesleyan pool and his lunches out twice a month with his

old colleague Richard Adelstein. His brain became so damaged

that he could not form a plan to get the bathroom on time when

he needed to but not damaged enough to keep him from being

ashamed and remorseful when Toni or my mother had to wipe

the shit from his bottom.

His life went on, thanks perhaps to his pacemaker, and he

could do nothing about it but endure. The tipping point had

come. Death would have been a blessing, and living was a curse.

As he put it to my mother one day, in his classic, understated style,

“Unfortunately, I come from long-lived people.” As Toni remem-

bered it, “He was confined to the house, and that was horrible.

He would sit in a chair with a book and just sit there. There was

nothing left for him. The only time I saw him happy was when you

visited. When you were around, he was

on the page.

He adored

you: you were Daddy’s little girl. Otherwise, it was take a nap, take

a nap, there was nothing else left. He liked to eat, and that was it.”

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 149

1/31/13 12:27 PM

150

katy butler

*

*

*

In California, I woke up some mornings in a fury. Why had

his doctors not let nature take its course? If the pacemaker

had never been implanted, I thought, my father might well

have been out of his misery, and so would my mother and me.

I understood very little about the device then, and I thought

that the only way to disable the pacemaker was to subject my

father to a second surgery—a path which seemed unthinkably

cruel, dangerously close to euthanasia, and, practically speak-

ing, impossible. I did not curse the mysterious ways of God, in

whom I did not believe, for keeping my father alive. I cursed

the machinery of man for disrupting the natural order, which

over millions of years of evolution had designed our hearts and

brains to fail at pretty much the same time. Where was Dr.

Rogan now, I wondered, to see what my father’s bonus years

had bought? Would he come over to my parents’ house on Pine

Street and look after my father for a single day?

When I called my brother Jonathan and vented, he joked

darkly on the phone about putting a pillow over my father’s

head. I told him about Temple Lee Stuart, a woman who lived

one town away from me in Sausalito. She’d pled guilty to man-

slaughter and was sentenced to six years in prison for smother-

ing her eighty-eight-year-old mother with a pillow in her nursing

home bed. The daughter called it a mercy killing, and main-

tained that her mother had repeatedly said she wanted to die.

Temple had been the only one of her mother’s children who

regularly visited the old lady. Temple had confessed to a brother

who lived out of town and had been arrested after he turned

her in.

On New Year’s Eve at the close of 2006, the worst, most

hopeless year so far of my father’s long life, I wrote out a prayer

in my despair and put it into my “God Box”—a coffee can onto

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 150

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

151

which I’d glued National Geographic shots of canyons, African

rock paintings, and other images of the sacred that I craved,

despite my lack of conventional religious belief. A friend in a

twelve-step program had recommended it as a technique for

letting go of what could not be fixed. “Please take care of my

mother,” I wrote. “Lead her to respite. Help me let go of trying

to control her and solve all of her problems. Help me flourish

creatively and personally whether she is happy or not. Please

help her let go, and let Jeff die.”

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 151

1/31/13 12:27 PM

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 152

1/31/13 12:27 PM

IV

Rebellion

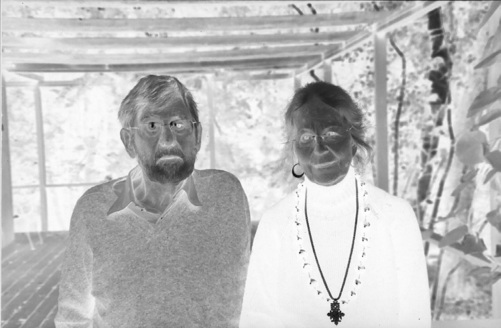

Jeffrey and Valerie Butler, Pine Street, Middletown, Connecticut, 2006.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 153

1/31/13 12:27 PM

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 154

1/31/13 12:27 PM

The

Sorcerer’s Apprentice

In January 2007, five months after my father’s disastrous stay

at YaleNew Haven Hospital, I interviewed a woman named

Katrina Bramstedt who worked for the Cleveland Clinic. I

did not immediately understand how her work applied to my

family’s dilemmas, but soon enough I would. I was looking for

science stories to write, and she was a hospital bioethicist, a

member of a relatively new profession propelled into being by

the life-prolonging machines in the ICU. Employed by the hos-

pital, Bramstedt functioned somewhat like an informal judge,

setting out and applying the rules when families, patients, and

medical staff were at odds about whether to permit an organ

transplant, discontinue life support, insert a feeding tube, or

try a painful and possibly hopeless—and then again, possibly

lifesaving—treatment.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 155

1/31/13 12:27 PM

156

katy butler

Most of her consults involved power struggles between doc-

tors and families over how to treat—or stop treating—desper-

ately ill patients in intensive care, ravaged by deadly infections

and kept alive with drugs, feeding tubes, respirators, and dialy-

sis. She had her work cut out for her. In the ICU, there was

no such thing as natural death, and few were comfortable with

the timed event that had taken its place. Half the time, doctors

wanted to keep going when families wanted to let go, and half

the time, families—especially, but not only, African-American

families—wanted to keep going when doctors wanted to quit.

Sometimes doctors ignored advance directives from patients or

even ripped them out of the chart. Sometimes a family would

balk at implanting a feeding tube in a demented relative, only to

hear a doctor say something like, “Nobody starves to death on

my watch.” Sometimes doctors complied when a long-estranged

son or daughter—commonly referred to in hospitals as “The

Nephew from Peoria”—flew in at the last minute and insisted

that everything be done, even things that doctors and other fam-

ily members thought were torturous, wasteful, and hopeless.

When fragmented families collided with a fragmented medical

system, the results could be disastrous.

An undercurrent of realistic worry ran through medical staff,

administrators, and the in-house department, usually headed

by an attorney, known as Risk Management. . In a handful of

extreme cases scattered across the country, distraught husbands

and fathers had entered ICUs with guns and disconnected a

half-dead child from a respirator or shot a comatose wife in

the head. On the other hand, if too much morphine was given,

or too little done to try to save a life, a Nephew from Peoria

might sue for negligence, or a local district attorney might

even consider charges of manslaughter. A single unnecessarily

prolonged intensive care death could cost a hospital well over

$300,000—money not recovered from Medicare, which usually

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 156

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

157

paid a lump sum based on the patient’s diagnosis, no matter

what the hospital’s costs. The families, meanwhile, were often

in shock: staggering to absorb reams of data from a rotating cast

of stranger-specialists who each zeroed in on a single organ and

did not seem to talk to each other; fearful of death; ignorant of

the limits of medicine; guilt-stricken and religiously conflicted

about ending life support; agonized by a relative’s suffering; and

hoping against hope.

In bland, untidy conference rooms edging the ICU, special-

ists asked families they’d never previously met to assent to the

removal of life support, and spouses and children pondered

questions—spiritual, legal, and medical—they’d rarely consid-

ered before tragedy hit. Did they have the right to say no to a

doctor? To force a doctor to continue treatment? Was it God’s

will to do everything possible to prolong a life, no matter how

much someone beloved was suffering? Was it suicide to refuse

medical care? Was it murder not to give it? Was it a sin? And

how were they to decide when the people they loved could no

longer speak for themselves?

Out of this ongoing moral and logistical chaos, bioethicists