Kokoda (41 page)

Now though, the problem was that as well as manning the 39th’s fall-back position at Alola, it was also the 53rd’s job to patrol and defend a tributary track which ran parallel to the Kokoda Track along the other side of the Eora Creek Valley. It was a route that bypassed Isurava entirely before rejoining the main track, and Honner had real worries that the Japanese would get smart and push along this track against the weaker 53rd, all the way to Alola. If that happened, the 39th would be cut off from their supply line and the route by which their wounded were to be evacuated. Simply put, they would be finished as a fighting force.

Meanwhile, the men of the 39th continued to dig in and get ready. On rare occasions when they could get a break, some of the more optimistic soldiers would take time out to write letters home on the back of dog-biscuit packets. Others would sacrifice the paper from cherished letters they had received from home as cigarette paper—the best was airmail letters—to wrap the dried tea leaves they used as tobacco. Certainly, the taste of such ‘cigarettes’ was deadly, but it did take their minds off what lay ahead, which they all knew was going to be a whole lot deadlier. And sometimes, too, they would do it all, reading and writing their letters, sucking on a cigarette and thinking about what they were fighting for in the first place. They were fighting for home; fighting to stop the Japs getting any closer; fighting to keep their loved ones safe. Someone had to do it, and it was

them

. There was nothing else they could do but get on with it.

The continuing paucity of ‘bullets and tucker’ as the men constantly referred to the terrible twin, was an ongoing problem. Supplies were so low that the men were severely rationed in what they could eat and when, perchance, a tin of pears, for example, might be scrounged from somewhere, it was often the platoon leader who would dole it out spoonful by spoonful to his section as they lined up. Something as seemingly inconsequential as a small pouch of sugar that had been salvaged from a burst bit of biscuit bombing was guarded like the crown jewels. Craving sweetness, some of the men had tried sucking on bits from the small sugar-cane plants that the village had in their market garden, but all that did was make you thirsty.

At least there was a precious bit of good news that helped to lighten the mood. Just four days after Honner had taken full command, a wonderful message came down the line. The 2/14th Battalion—all Victorians who’d served in the Middle East—had landed in Port Moresby, and were already coming up the track. The 2/16th were just a day behind them. With them would come a whole slew of the hoped-for supplies, and that was just about the finest news of all.

There had also been some indication that the Japs were doing it equally tough. On both sides of the battle it was standard procedure to search the body of every killed enemy soldier to strip them of ammunition and supplies as well as gather information, and time and again the Australians had been amazed to find that the sum total of supplies carried by these blokes for a

whole day’s

fighting were the few concentrated vitamin tablets which they always had, and a small, grisly ball of rice wrapped in some kind of seaweed. It was extraordinary how little these blokes could live on. As hungry as the Australian soldiers were, they could barely bear to eat it, but they made themselves anyway. Ditto the vitamin tablets. If those little pills kept the Japs going, then they had to offer

something

in the way of nutrition. When the Japanese found dead Australian soldiers, on the other hand, the principal thing they went after were the sturdy Australian boots, much better than their own canvas and rubber sandshoes which never came to grips with the slippery track— seemingly the single failure in Japanese equipment.

159

Disaster. Complete disaster. On the night of 18 August 1942, no fewer than three thousand crack Japanese soldiers of the 28th Infantry Regiment, under the leadership of Colonel Kiyono Ichiki, landed at Taivu Point just to the east of the Guadalcanal airbase and carefully moved forward under the cover of darkness. Regarded as Japan’s most elite unit, their commitment to their task was total. Each soldier now stealthily moving forward in the darkness had a document stating firmly that if they did not take Guadalcanal they would not be returning to Japan alive. At least this particular mission shouldn’t be too hard. Colonel Ichiki had personally told his men that ‘Americans are soft—Americans will not fight—Americans believe that nights are for dancing’, and in any case his Intelligence had told him that there were only going to be two thousand of the Americans defending the position.

Alas, alas, for the Japanese, well over fifteen thousand American Marines, forewarned of the landing, were waiting for them and all but wiped the invaders out. Most of the Japanese survivors fled into the jungle. Colonel Ichiki didn’t. In the tradition of the samurai who had failed at his task, he first burnt his regiment’s colours and then committed harakiri. There was no other recourse.

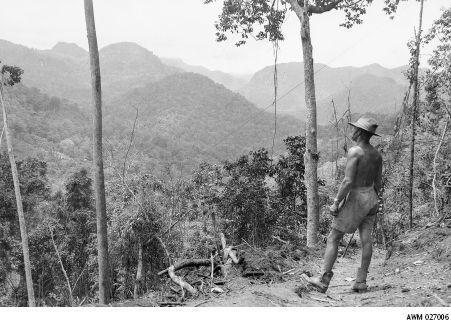

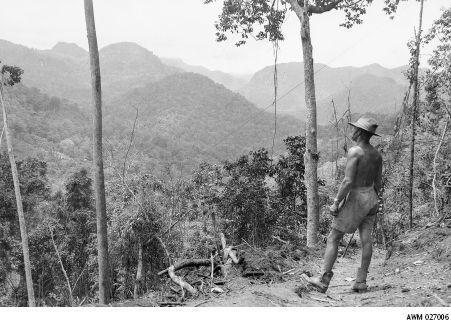

At last, they were getting close and were within just one day’s march of Myola. Thank God. After five days footslogging along the Kokoda Track, the men of the 2/14th knew that their destination and the battle true was just up ahead. Which was good. After so many weeks and then months of waiting since returning from the Middle East, and then travelling, and then footslogging, and then more footslogging still, and all the bloody stuffing around, they were ready for the real battle to begin. Even for those who had seen action in such distant climes as Syria, Australia had never seemed further away.

And so, too, relief for the reinforcements from the 144th Regiment, who had left Rabaul by ship on 16 August, and who were getting close, within a day’s march of the enemy Australians. It had been a long haul from the landing, making their way through the steaming humidity and overwhelming heat, across raging rivers, up mountains, along muddy tracks, all in an environment never imagined before, but they were getting there. If there was a worry, it was the news filtering back from the front that the Australians were providing more resistance than they had been thought capable of.

As Second Lieutenant Noda Hidetaka noted in his diary on Saturday 22 August, while situated at a point very near Kokoda: ‘I hear that the enemy are young, vigorous and brave. Against this enemy we have this terrain also. It will be necessary for us to put forth our utmost endeavour and uphold the prestige of our Imperial Army.’

160

Lieutenant Hidetaka still wasn’t feeling as ruthless as he would have liked, but just maybe he was getting there. He was trying, anyway.

At last, their papers had come through. The only proper place for a war correspondent of any description was the front and, after a week of waiting Osmar White, Damien Parer and Chester Wilmot now had official permission to trek to the battlefront at Isurava. The three formed a fairly natural trio as each was the leader in his field, and they were good friends besides. The only real condition laid down upon them was that they were not allowed to take native porters, as those crucial members of the war effort were in such short supply that not a single one could be spared for something so inconsequential as journalists. Apart from that, though, so long as they hauled their own supplies they were free to set off immediately up the track. There proved to be just one problem…

Just when they were readying to depart, Damien Parer received a cable from the Department of Information, advising him that instead of making this trek to a genuine battlefront, he was required to return to Townsville immediately to make a stunt film for American consumption. Distraught, Damien did the only thing he could think of. He drove out to New Guinea Force HQ to see General Rowell and ask his advice.

It was a wise move. Rowell realised that the best way for both the Australian people and the likes of Blamey and MacArthur to understand what conditions were really like at the battlefront was to have film-makers of the calibre of Parer up there. In his view, such a venture was a more valuable contribution to the war effort than making stunt films for Americans.

161

In a snap decision, he immediately told Damien Parer not to give it another thought. He would cable Australia that unfortunately the film-maker had already left for the battlefront and he was not going to recall him.

It was jolly decent of Rowell to take such action on his behalf and with this blessed reprieve, Damien raced away to tell Ossie and Chester that he could accompany them after all. Only shortly afterwards they were on their way, after hitching a lift to Ower’s Corner, and setting off up the track.

Up in the village of Efogi, Stan Bisset was just starting to think about turning in for the night, when word was passed to him that his brother Butch was wondering if he’d like to come down to the southwestern corner of the bivouac section and have a singalong with the fellas of his Platoon Company 10. That’d be Butch all right… Of course he’d come, Stan assured the private who’d brought the message. Tell Butch he’d be there in fifteen minutes.

It didn’t take long to find Butch’s platoon, even in the darkness. As always when looking for his brother, Stan followed the sound of the laughter and sure enough, by the glow of the campfire, he found Butch finishing off just one more of his rib-tickling stories as the others of the platoon fell about laughing, marvelling that one man could know so many amazing yarns and keep telling them without repeating himself. They’d all been together nigh on two years now, and Butch still somehow managed to keep it up. On seeing Stan arrive, Butch leapt to his feet, gave his brother a strong handshake, and prevailed upon him to sing some of their favourites, while they all sang along.

And so they did. In the black New Guinea night, the soaring voices of the Australian platoon were soon joined by the voices of others who gravitated there from their own campfires. This close to the front, fires were not allowed unless there was a thick mist, but on this night the fog had rolled in a treat.

Perhaps the high point was when Stan sang the one which had always been Butch’s favourite, the Irish ballad, the

‘

Mountains of Mourne’. In his beautiful, resonant baritone, Stan sang it as never before.

Oh, Mary, this London’s a wonderful sight,

With people here working by day and by night,

They don’t sow potatoes, nor barley nor wheat,

But there’s gangs of them digging for gold in the streets,

At least when I asked them that’s what I was told,

So I just took a hand at this diggin’ for gold,

But for all that I found there I might as well be,

Where the Mountains of Mourne sweep down to the sea.

As Stan kept singing, Butch kept beaming at him, prevailing upon him to sing just one more song, even though it was now getting quite late. Stan of course obliged and, as his singing of course evoked memories of other times, he beamed back at his brother as they recalled singing around Uncle Abe’s old piano on Sunday afternoon after the roast.

Despite the happiness of the moment, oddly enough, Stan felt something like a shadow fall across him whenever he looked at Butch, roaring the songs out by the firelight. It was the shadow of premonition that something terrible was going to happen to his brother, that he was going to… well, that he was going to die. Stan shook it off as they kept singing and would give the chorus even more gusto as if to expel that thought forever, but then, he would look at Butch and the thought would come again. Anyway, time to turn in. The fog had suddenly made things very cold.