Legions of Rome (57 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

All the while, the Roman noose was tightening on Gaul. The 21st Rapax, formerly a Vitellianist legion, had reportedly already crossed the Alps. The 6th Victrix and 10th Gemina legions were marching to the Rhine from Spain. The famous 14th Gemina Martia Victrix Legion was being ferried over from Britain by the Britannic Fleet. Three more legions would cross the Alps from Italy, each using different routes: the 6th Ferrata and 8th Augusta from Mucianus’ army, and the recently formed 2nd Adiutrix Legion.

Mucianus also left Rome and headed for Gaul. With him went 19-year-old Domitian, Vespasian’s youngest son, who was chafing to see action. Mucianus convinced the headstrong teenager that it would be more seemly if the generals were left to do the dirty work, while Domitian stood back and took the credit. Mucianus and Domitian would base themselves at Lugdunum in south-central France, to add the weight of the imperial family to the offensive.

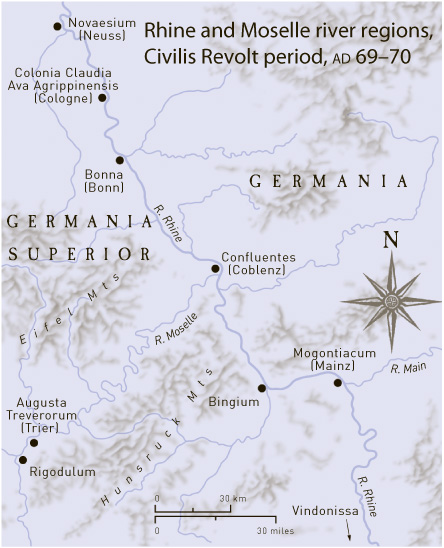

After the forward commander, Cerialis, crossed the Alps, he split his force in two. Sextilius Felix took the auxiliary infantry via Raetia with orders to march up the east bank of the Rhine, while Cerialis led the 21st Rapax Legion along the western bank, with the two forces converging on Mogontiacum. Along the way, Cerialis was joined by the Singularian Horse, an elite cavalry unit formed the previous year by Vitellius from the best German cavalrymen in the Roman army. The unit was ironically commanded by a Batavian, Julius Briganticus, Civilis’ nephew. But Briganticus was loyal to Rome, and hated his uncle Civilis with a passion.

As Cerialis neared Vindonissa, the rebels occupying it withdrew. East of the Rhine, the Treveran general Tutor heard that a Roman army was approaching from the southeast, and quickly mustered a rebel force including the legionary defectors from the 4th Macedonica, 5th Alaudae, 15th Primigeneia, 18th and 22nd Primigeneia legions. Tutor prepared an ambush, into which Felix’s advance cohort walked; it was wiped out.

Scouts then warned Tutor that a second, much larger Roman force was moving up the opposite bank of the Rhine. When it was learned that it was the 21st Rapax that was approaching, the legionaries under Tutor refused to fight these men who had recently served with them on the Rhine. Tutor was forced to retreat, accompanied by just his loyal Treveran troops, leaving the legionaries to march to Mogontiacum and await Cerialis’ arrival.

Skirting Mogontiacum, Tutor withdrew west to Bingium (Bingen), where the Rhine is joined by the River Nahe. Roman commander Felix, crossing the Rhine via a river ford, came up behind Tutor and launched a surprise attack. The rebels were routed, and Tutor fled to join Classicus, further north. At the same time, Cerialis and the 21st Rapax Legion victoriously entered Mogontiacum, to be greeted by the former defectors. He told the once mutinous legionaries that they would soon have their chance to prove themselves, and took them into his force.

With Tutor’s comprehensive defeat at Bingium, the Treverans were in a state of panic. Thousands who had taken up arms now disposed of them. Many of their elected officials sought asylum further south with tribes loyal to Rome. Other city senators went north to join Civilis. But Valentinus remained in control of Augusta Treverorum, still with a sizeable force of Treveran fighting men. Civilis and Classicus, stung by Tutor’s defeat, assembled their scattered forces, sending messages to Valentinus telling him not to risk a decisive battle with the Romans until they could join him.

AD

70

XXIX. BATTLE OF RIGODULUM

Turning the tide

Cerialis decided to deal with Valentinus at Augusta Treverorum before he ventured further north against Civilis and Classicus. As he approached the Treveran capital, he sent officers to lead the men of the 1st Germanica and 16th Gallica by the shortest possible route back to Augusta Treverorum, from which they had previously escaped, to link up with his army.

With the equally disgraced men of the 4th Macedonica, 5th Alaudae, 15th Primigeneia, 18th and 22nd Primigeneia legions from Mogontiacum in his army, Cerialis marched rapidly west to attack Augusta Treverorum. In three days, his force

covered the 75 miles (120 kilometers) to the Moselle, arriving at a place just outside Augusta Treverorum which the Romans called Rigodulum. This is likely to have been where a stream called the Altbach joins the Moselle. Since long before Roman times the Treveri had maintained a sacred sanctuary there.

Ignoring the advice of Civilis and Classicus, Valentinus had brought his Treverans from behind Augusta Treverorum’s walls to Rigodulum, having levied every able-bodied man of the city to his standards. Intending to make a stand with the river to one side and surrounded by the foothills of the Eifel and Hunsruck mountains, he built a fortification into a bare hillside, strengthening the position with ditches and stone breastworks.

Cerialis attacked without hesitation. While his infantry made a frontal assault up the hill, the Roman general sent a detachment of Briganticus’ Singularian Horse to find an attack route from the rear. The progress of the lines of legionaries and auxiliaries advancing up the hill was slowed briefly as they came within range of the defenders’ missiles, but once through, they charged forward and stormed the poorly fortified position. With the benefit of training, experience and superior numbers, and with one-time rebel legionaries keen to prove themselves, it was no contest.

“The barbarians were dislodged and hurled like a falling house from their position.” [Tac.,

H

,

II

, 71] As the Romans swept over the defenses, Valentinus and his chief lieutenants fell back up the hill, and into the hands of the Roman cavalry, which had found a route through the hills behind the rebel position. Those Treverans not

killed were captured. Valentinus was among the captives. The Battle of Rigodulum was a swift and crushing defeat for the “Empire of Gaul.”

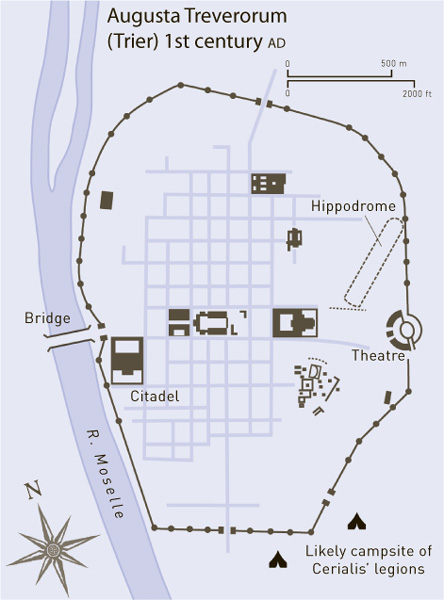

Next day, the gates of Augusta Treverorum were thrown open to the Roman general. Situated on the right bank of the Moselle, the city had been founded as a military post by Augustus in around 15

BC

. The Treveri had built a settlement close by which, in the reign of Claudius, had gained Roman colony status and the name of Colonia Augusta Treverorum. In Claudius’ reign, too, a large timber bridge had been built across the river, on stone piers, and the city that grew beside the Moselle swiftly became prosperous as a commercial crossroads. As Cerialis entered Augusta Treverorum, his men urged him to destroy the city, the birthplace of Classicus and Tutor. But Cerialis was determined to restore firm discipline to the legionaries who had returned to their standards, and letting them run riot in the city was no way to achieve that.

That same day, the men of the 1st Germanica and 16th Gallica legions arrived from Metz and made a camp outside the city. There were none of the customary cheers and friendly greetings exchanged between the legions of Cerialis and the new arrivals. Swathed in guilt, the men of the 1st and 16th stood around with eyes fixed to the ground. When some of Cerialis’ legionaries went to their camp to console and encourage them, they were so ashamed they hid in their tents. Big, strong legionaries from both camps were seen to shed silent tears.

Observing this, Cerialis assembled all the Roman troops and addressed them. The men of the legions caught up in the rebellion must now consider this day the first day of their military service and of their allegiance to Rome and the emperor, he said. He promised them that their past crimes would be remembered neither by the emperor nor by himself. And an order was read to every maniple that henceforth no soldier was to mention past mutinies or defeats. Cerialis then brought the men of the 1st and 16th into the main camp to join the rest of the army; they were outcasts no more. [Ibid., 72]

At an assembly of the Treveri and Lingone people in the city, Cerialis declared, “It is by my sword that I have asserted the excellence of the Roman people.” [Ibid., 73] He urged the population to swear off rebellion and accept the presence of Roman arms and the payment of Roman taxes as the price of peace. Having heard the legions call for the destruction of the city, the residents welcomed Cerialis’ option.

This policy of non-reprisal was applied throughout rebel territory on the orders

of Mucianus, who sent the praetor Sextus Julius Frontinus to take the formal surrender of Julius Sabinus’ Lingones. Frontinus was to write: “The very wealthy city of the Lingones, which had revolted to Civilis, feared that it would be plundered by the approaching army of Caesar. But, when, contrary to expectation, the inhabitants remained unharmed and lost none of their property, they returned to their loyalty, and handed over to me 70,000 armed men.” [Front.,

Strat

.,

IV

,

III

, 14]

Captured Treveran general Valentinus was sent to Lugdunum to appear before Mucianus and Domitian. After hearing the loquacious Valentinus put his case for a free Gaul, the no-nonsense Mucianus ordered his immediate execution. Valentinus went to his death claiming he would be remembered as a martyr to the cause of a free Treveran people. [Tac.,

H

,

IV

, 85]

At the same time, Civilis and Classicus sent a letter to Cerialis claiming that the emperor Vespasian had died. This news had been suppressed by Vespasian’s aides, they said. They also assured Cerialis that Italy was once more locked in civil war. The pair suggested that Cerialis leave them as rulers of their own states and go home. Failing that, they said, they would gladly fight him, and beat him, with German reinforcements from across the Rhine. Cerialis merely sent the rebel emissary south to Lugdunum, for the amusement of Mucianus.

Several days later, Cerialis was sleeping peacefully at Augusta Treverorum when he was awoken by panicking staff. Civilis, Classicus and Tutor had swept down from the north in two large columns, one via the Moselle Valley, the other swinging around to the east and coming over the mountains behind Augusta Treverorum. It was a classic pincer movement, perfectly executed. Between them, the two forces had literally caught the legions camped outside the city napping.

AD

70

XXX. BATTLE OF TRIER

Civilis counter-attacks

In the early hours of the morning, Germans had seized the bridge linking Augusta Treverorum with the far bank of the Moselle. Simultaneously, Civilis and his troops had burst into the Roman legionary camp outside the city, where vicious hand-to-hand fighting was taking place. Some parts of the camp had already been lost.

Civilis had been against this attack. Tutor had urged the assault, before Roman reinforcements reached Cerialis from the south. Classicus had voted with Tutor. Outvoted, Civilis had agreed to lead the mission, which now had the appearance of an imminent rebel victory. Cerialis, rising from his bed and picking up his sword without waiting to strap on his armor, hurried to the city gate that opened on to the Moselle bridge. Taking the Roman troops bunched there, the general led a counter-attack that threw the Germans off the bridge.

Leaving a detachment to hold the bridge, the general took the remaining men through the city at the run to the Roman camp beside the river. The first troops Cerialis came upon after he passed through a shattered camp gate were men of the 1st Germanica and 16th Gallica legions. Their standards stood defiantly, but few men defended them; the two eagles looked close to falling into rebel hands.

“Go tell the emperor,” Cerialis yelled to the men of these two legions, “or Civilis and Classicus, as they’re closer, that you have deserted yet another Roman general on the battlefield.” [Tac.,

H

,

IV

, 77]

This jerked the 1st and 16th into action. Their cohorts rallied, charged the enemy, and saved their standards. While legionaries throughout the camp were compressed among tents and wagons by the enemy onslaught, and were finding it difficult to fight in formation,

the men of the 21st Rapax regrouped in open space. Forming a dense line, the Rapax bore in on rebels who had turned their backs on the fighting to loot Roman baggage. Their drive sent tribesmen fleeing from the camp thinking that Roman reinforcements had arrived from Italy and Spain. Maintaining the momentum, Cerialis chased the fleeing rebels down the Moselle Valley toward the Rhine. Late in the day, Cerialis’ troops came upon, and overran, the camp where the rebels had camped the previous night.