Lyttelton's Britain (13 page)

Read Lyttelton's Britain Online

Authors: Iain Pattinson

T

HE

H

AMPSHIRE TOWN

of Basingstoke boasts an historical tapestry richly woven with culture. Evidence of an early settlement and its trading links may be seen at the town’s Willis Museum, which houses Roman pottery found at Silchester camp and a hoard of bronze and iron European coins, retrieved from Basingstoke’s parking meters.

Pride of place in the town’s museum goes to the skull of a 300,000-year-old male, discovered locally in 1962. A primitive being with short legs and long arms, ‘Basingstoke Man’ is described by experts as genetically somewhere between ape and human. Sadly they don’t know anything about that old skull.

The name ‘Basingstoke’ is first mentioned when William the Conqueror commissioned the Domesday Book, where it is described as a settlement with a population of some 200-odd people, but then the Normans could be a bit judgmental.

The result of Britain’s first experiment into genetic modification holding a large marrow

Basingstoke’s early prosperity was based on the production of wool. Sheep were raised locally, and their wool was cleaned by being beaten with a mixture of water and clay by large wooden hammers driven by watermills. Later, in a more enlightened age, it was decided to shear the sheep first.

Basingstoke’s first hospital was founded in the early 13th Century and dedicated to St John the Baptist. However, medical treatment was crude in the extreme with amputations performed using a large, blunt axe, although a sharp one could be made available if you went private.

Basingstoke saw its ultimate test with The Black Death of 1347, which left the town decimated. ‘’Tis a sight to vex the spirit: Them the Lord hath spared do move with hollow cheeks and eyes that are sunken unto their sockets. Broken are they with despair and the pity of their existence. A stillness most dreadful and ghostly doth cloak the whole town withal’, but other than those comments, the RAC Guide gives it two rosettes.

In 1392 the town was destroyed by fire and had to be completely rebuilt. The king subsequently made the ‘good men’ of Basingstoke into a corporation, giving them the right to use his common seal, as the sensitive nostrils of amphibious mammals made them useful as smoke alarms.

1657 saw the Basingstoke Witch Trials, where a woman named Goody Turner was found guilty of practising witchcraft. After surviving a ducking in the pond, an angry mob then tried to burn her at the stake, but she was too damp and kept going out. While they were drying her off, she asked for seventeen burglaries, two serious assaults and one attempted murder to be taken into account, so her sentence was reduced to community service.

Nearby is the home of the Dukes of Wellington since 1817, where visitors can see the grave of the first Duke’s stallion, Copenhagen. It was after the Battle of Waterloo, where Wellington famously spent 18 hours in the saddle, that a grateful nation gave him his country seat – although he couldn’t use it for at least a fortnight. Copenhagen was buried at Stratfield Saye House with full military honours. The grave is marked by a simple headstone and four hooves sticking out of the ground.

Jane Austen lived at nearby Steventon, and during her time there started a romance with a Basingstoke man, widely believed to be a forester, but their engagement lasted only one night. History doesn’t record what suddenly prompted her to leave Acorn Willy Jenkins.

One of Basingstoke’s most famous sons is Thomas Burberry, inventor of rain-proof gabardine. He perfected his proofing method after noticing that an oily substance from wool made a shepherd’s trousers water resistant after prolonged contact with sheep. And it must have taken a mighty inventive brain to witness that sight and think about raincoats.

Famous names associated with Basingstoke include Hollywood movie star Elizabeth Hurley, who as a young girl was born and educated in the town. Her primary school teacher recalls Elizabeth taking her first acting lesson, and having seen her many films, the pupils were keen to invite her back for a second one.

The family of Sarah, Duchess of York, came from the nearby village of Dummer, which is presumably why she is constantly referred to as ‘one of the Dummer Fergusons’.

Another Royal connection is that of Arthur Nash, official broom maker to Her Majesty the Queen, who lives in Basingstoke. Her Majesty doesn’t believe in modern contrivances such as vacuum cleaners, when carpets can be cleaned perfectly well simply by ringing a small bell.

Eton, 1936, shortly after a small hole appeared in the wall of the adjoining Nurses’ Home changing rooms

W

INDSOR

gave its name to a type of chair, a knot and most famously, a soup, although this was before the Royal Borough changed its name from ‘Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom-on-Thames’.

But a stone’s throw across the river is Eton, with its world-renowned school. A browse through the school records reveal that: ‘famous Old Etonians include the Duke of Wellington, William Gladstone, George Orwell and Humphrey Lyttelton, the jazz musician and panel game chairman’. Curiously they don’t record what the other three were famous for.

Windsor has a proud association with the Royal Family. It was in 1917 that the house of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha took their new name from the place where they loved to spend so much of their time. By the same tradition, when the young Sarah Ferguson married Prince Andrew, she naturally assumed the title ‘Duchess of Airport’.

For the finest view of Windsor Castle it is best approached through ‘Henry VIII’s Gateway’, which thanks to a recent merger, is now officially known as ‘Henry VIII’s Budgens’.

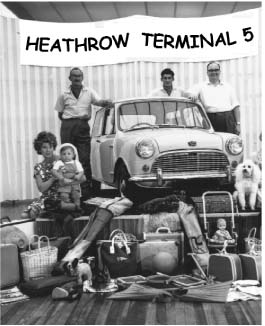

A family enjoys the third week of their holiday, summer 2008

A short journey out of town takes you to Windsor Safari Park, where if you’re lucky, you might glimpse a pride of lions in search of wildebeest migrating south across the vast plains of the Thames Valley. You might also like to pay a visit to the successful new ‘Legoland’ theme park next door. For a small fee, parents can take their children to enjoy a large area of toy buildings constructed out of plastic bricks. Alternatively, they can save their money and take the kids to Milton Keynes for the day.

Windsor, where organic products, including banana oil car-wax, were developed

R

EADING

is a fine town steeped in a rich history. When the Norman King Henry I’s body was returned from battle in France, his remains were buried at nearby Reading Abbey, although his heart was buried at Rheims, his eyes and tongue at Calais, while his bowels remained at Rouen, although that was put down to a dodgy frog-leg fritter.

The novelist Jane Austen was educated in Reading’s Abbey School, and while her mythical Northanger Abbey is widely accepted by literary experts to be based on Reading Abbey, this is disputed, mainly by the Northangrian monks of Northanger Abbey at nearby Northanger.

William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633, was born in Broad Street, where WH Smith stands, which is evidenced by the Laud family crest of a crossed pen and pencil set argent, topped by Readers’ Wives rampant.

Britain’s oldest known song was written in Reading in about 1240. Its Early English title: ‘Sooma is icoomen in, lhooda sing cukku’, which to our modern ear sounds quite meaningless, actually translates as ‘Agadoo, doo, doo, push pineapple, shake the tree’.

Reading was also the birthplace of William Fox Talbot, who brought photography to the masses. His portrait was recently restored and hangs in the Reading Gallery, complete with a

little sticker in the corner pointing out where the artist inadvertently left his thumb over the canvas.

Visitors may wish to take in the memorial to John Blagrave, the eminent 19th Century mathematician and ‘father of Algebra’, although, after being ribbed at school, little Algebra later changed his name on the advice of his aunt, Mrs Emily Quadratic-Equation.

World fame was brought to Reading by Joseph Huntley, of Huntley and Palmer fame, the philanthropist who provided a row of terraced houses for the poor. Sadly, at the official grand opening, the ones at each end were found to have developed cracks and quickly crumbled.

Probably the town’s most famous temporary resident was Oscar Wilde, who, in that less enlightened Victorian time, served two years’ hard labour in Reading’s notorious prison for what the town’s guide describes as a ‘social indiscretion’. According to Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar was as indiscreet as a nine bob note.