Lyttelton's Britain (16 page)

Read Lyttelton's Britain Online

Authors: Iain Pattinson

Shakespeare’s birthplace is certain and many famous characters down the years have visited the very room in which he came into the world, and many have scratched their names in

the glass of his window. Visitors can still make out faint signatures that include Sir Henry Irving, Mr Oscar Wilde, Miss Lilly Langtree and Mr Pilkingtons Safety Glass.

C

OVENTRY

enjoys a fascinating history and was long known for the manufacture of fine timepieces. One J. W. Player made the most accurate wristwatch ever, but as it cost over a million pounds to make, his company went bust, exactly 36 hours, 28 minutes and 2.47533877 seconds later.

The city has several Royal connections. Mary Queen of Scots was held in Coventry and was given a small dog which she took with her to the Tower of London. The animal was there at her grisly end, even as the axe fell. Then a witness shouted ‘fetch!’

The name ‘Coventry’ entered the language as a popular phrase during the English Civil War, when Royalist prisoners were sent to the city. As the locals were Parliamentarian, they refused to speak to them, and hence the common expression: ‘Sod the Cavaliers.’

The earliest promoter of Coventry was the Earl of Mercia, who played an important role in stimulating growth for the city’s founding fathers, as did his wife Godiva when she rode naked through the streets. In fact, all the townsfolk agreed to avert their gaze, except for one, ‘Peeping Tom’, who watched her single handed, and as a result went blind.

Another famous event in the city was a duel between Coventry’s sheriff, the Earl of Hereford, who challenged the Duke of Norfolk. When the latter arrived at the city gate in search of a bride, he was called to by Hereford who asked:

‘Identify yourself and your intentions toward my daughter.’ The gauntlet was cast down after the reply: ‘Norfolk and Good’.

Modern Coventry is noted for its car manufacturers, including Jaguar, who, in their brief return to Grand Prix racing from 2000 to 2004, did so much to secure a remarkable five consecutive world titles for Ferrari.

Before Coventry became so involved with heavy industry, the area was famous for its finely dyed blue fabrics. With only primitive equipment, the ‘woaders’ as they were known, had to compress layers of cloth into vats of dye using their body weight, by sitting on the top. They are long gone, but there is a small band that continues the noble art of dying on their arse. You can often hear them on Radio 4 on Mondays at 6.30 p.m.

Coventry City’s legendary goalkeeper, Dave someone-or-other, makes a superb save, much to the appreciation of City’s many adoring home fans

B

IRMINGHAM

is a vibrant city which is rightly proud of its long and fascinating history. A settlement there first grew in Anglo-Saxon times and was known as: ‘Beormaham’. ‘Beorma’ was a Saxon chieftain from the lowlands of Northern Friesland, and ‘Ham’ was what he had in his sandwiches.

After the Norman Conquest, Birmingham was recorded as a minor village in the Domesday Book of 1086, which stated that the land we know now as the city centre was valued at twenty shillings. Taking account of inflation, in today’s terms, economists estimate the value has risen to nearly twice that sum.

During the Middle Ages, as trade grew, many inns were established in Birmingham, which today boasts some of the oldest pubs in England. When the town was bequeathed by Henry VIII to the Earl of Northumberland, he arrived to find a Green Man, a Blue Boy, a Carpenter’s Arms, and no less than three Queen’s Heads. So he put them all in a bin bag and went to the pub.

The city of Birmingham is world-famous for its architectural heritage. The first parish church of St Martin’s was built by William the Conqueror using architects and craftsmen brought from Normandy. That these artisans possessed specialist knowledge unknown to the English, is commemorated in a tapestry in the chancel which reads: ‘This house of our Lord was constructed

by the grace of Norman Wisdom’, just below a picture of a little builder falling off a ladder.

The city’s fine town hall was designed in 1832 by the architect Joseph Hansom, who also designed the taxi-cabs which bore his name. This is why the town hall mysteriously disappears without trace when it’s raining.

Birmingham’s industrial origins go back to the 14th Century, when peasants finding iron ore and coal deposits started to experiment to produce hot smelting fires and to fashion basic farm tools. Only after decades of failure did they realise that iron doesn’t burn and lumps of coal make lousy shovels.

But they persevered and Birmingham’s reputation as an industrial centre grew steadily. By the 18th Century, the city was the power house of the Industrial Revolution and a massive canal system was built. With barges pulled by horses, the canals thrived until well into the 20th Century, when they were abandoned after becoming choked with drowned horses.

With the growth of waterborne transport, Birmingham boasted more miles of canal than Venice. Interestingly, when Marco Polo had travelled the known world, he was commissioned by the Venetian merchant princes to establish spice and silk routes to Cathay. Setting sail across to the shallow waters of the Lido, he looked back across the Renaissance splendour of the Piazza San Marco towards the Doge’s Palace and observed: ‘If only Venice had more canals it would be just like Birmingham.’

Birmingham’s armaments industry was greatly helped by the English Civil War. The city supported Parliament and 15,000 swords were produced and lent to forces garrisoned to take care of the town’s womenfolk. When peace resumed, the swords were returned, but as a symbol of what they did in Birmingham during the war, Cromwell’s men continued to wear the sheaths.

As Britain’s nuclear power programme took off, enriched plutonium was stored in many of Birmingham’s public buildings

Down the centuries, Birmingham armaments factories have supplied the military hardware used in every conflict from Waterloo to the Battle of Britain, and it was in light of this achievement that a special day was mooted in celebration of Britishness. The idea was to tag this on to an existing commemorative day, but no decision has yet been reached, as Trafalgar Day would offend the French, while VE Day would upset the Germans. So – too spoilt for choice then.

Modern Birmingham is the leading British producer of jewellery, making many thousands of engagement rings every year for Ulrika Jonsson.

The pioneering scientist Joseph Priestley came to Birmingham in 1788 and after three years’ work discovered oxygen. This came as a great relief to the townsfolk, who had had to hold their breath up till then.

Priestley also invented the fizzy soda drink, by devising a method of forcing large quantities of carbon dioxide gas into water. He gave it to many friends, who trumpeted his achievement around the city.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle lived and worked in Aston, where he regularly visited shops in Watson Street. It is recorded that, while short of a name for a new character, Conan Doyle spotted a sign there, and so was born ‘Dr Massive Golf Sale’. Another title of Conan Doyle’s was inspired by the famous printer and fellow Birmingham resident, John Baskerville. An ardent atheist, Baskerville requested that he be buried on unconsecrated ground in the garden of the family home. Sadly, he was later dug up by the dog.

The Victorian artist and poet John Ruskin married in Birmingham in 1872. However, Ruskin had led a sheltered life, and it is reported that on his wedding night he was so shocked by the sight of hair on his bride’s body, that he was unable to make love until she agreed to shave her beard off.

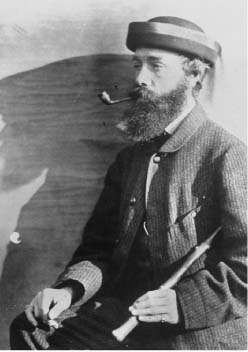

Wedding portrait, Mrs John Ruskin, Birmingham, 1872

Other famous Brummies include the political thinker

Joseph Chamberlain, whose sons Austin and Neville also left their marks. Austin lent his name to the popular car manufactured nearby, the Chamberlain Allegro GLX, while one-time mayor Neville Chamberlain did so much to help ensure the restructuring of the city centre when he failed to prevent World War II.

Names from the arts include the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, who became more popular when he dropped the name ‘Gerard’, donned a blonde wig, and sang the 1969 Eurovision entry ‘Those Were The Days’. And landscapes from the brush of local Victorian artist David Cox are regularly shown by the City Gallery in the best possible setting. It’s not difficult to understand why visitors flock in admiration every season when the curators announce they’ll display their beautifully hung Cox collection.