Lyttelton's Britain (24 page)

Read Lyttelton's Britain Online

Authors: Iain Pattinson

L

EEDS

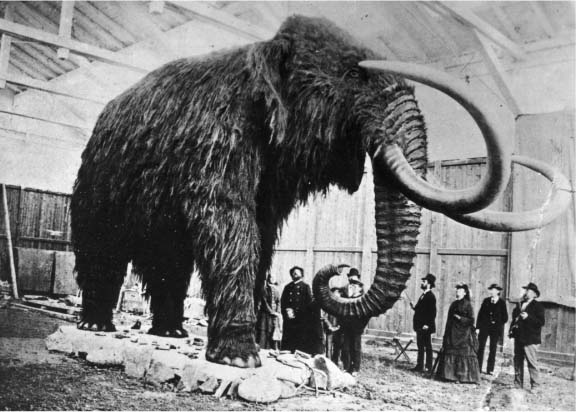

is a fine Yorkshire city that boasts a rich history. At the end of the Ice Age, settlers there found the Aire Valley inhabited by woolly mammoths, an abundant source of food, clothing and ivory for tools and implements. Evidence that this species of mammoth was even worshipped has recently been unearthed in a cave inscription which reads: ‘That’s the wonder of woollies.’

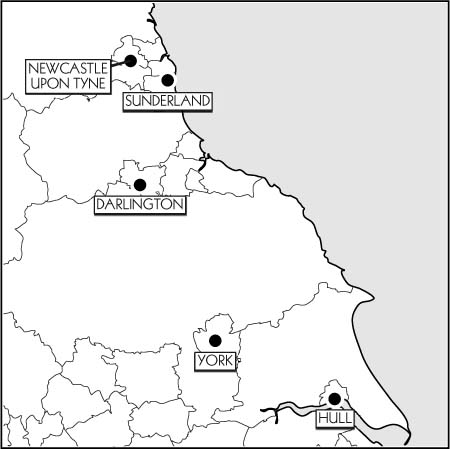

DFS mammoth sale, 1927

By the 13th Century, Leeds had grown to become the largest wool producer in England, and the prosperity of the town was based solely on all things woollen. Consequently, the population soared from a few hundred to over 6,000, at which point loose-knit condoms fell out of favour.

In the later Middle Ages, Leeds became famous for its annual fair. Villagers would travel from the whole of Yorkshire for the event, each arriving back home with woollen garments, legs of lamb, a hog’s head of mead and a dead goldfish in a plastic bag.

In 1534, one John Middleton wrote of Leeds: ‘It has a praty market, and one parocky charch reasonably well buildid’, for which he was awarded two out of ten in his spelling test.

During the Civil War, Charles I was a fugitive in Leeds and stayed at the Red Lion for threepence a night. Over a century later, when Lord Nelson visited, he stayed at the ‘Admiral’s Rest’ for half a guinea, while Lady Hamilton lodged at the ‘Whippet Inn’ for sixpence.

1756 saw the opening of the massive Cloth Hall, which was recently restored and cleaned by a team of workers, who folded it up and took it to the laundrette.

Wool production in Leeds only began to lose prominence with the Industrial Revolution. As industry grew, the Leeds to Liverpool canal was constructed. This was opened in 1816 in great ceremony by the two cities’ mayors, although it is recorded that the Mayor of Liverpool stole the show.

Leeds was really put on the map by the Industrial Revolution and the world’s first commercial steam railway opened there in 1814. Called ‘The Middleton Colliery Railway’, its advanced

technology and efficiency of operation was considered a modern marvel, when visited by the operators of Arriva Trains Northern.

During Victorian times, Leeds became a haven for Jewish refugees from Europe, Irish workers fleeing the potato famine and Indian families from the sub-continent. Evidence of this rich cultural mix is still to be seen in the tandoori gefilter fish stalls in front of Murphy’s Builders and Barmitzvah Services.

In 1872, Leeds Grammar was founded. The school still keeps a small collection of the artefacts bequeathed by their benefactor, John Harrison, who aimed to improve the city’s literacy. Despite his famous philanthropy, there seems to be no trace of his stamp collection.

In 1884, Marks and Spencer opened their first shop in Leeds, and took as their trademark St Michael, the patron saint of returned cardigans.

Another famous business to start in Leeds was that of John Waddington, who opened a shop on Bridge Street, which he visited every time he threw a double six. Waddington soon built a factory to produce board games, but this was the scene of rioting by Luddites, so-named because they refused to accept the new Ludo technology.

However, Waddington’s enterprise thrived until 1939, when the factory switched to helping the war effort. At one time they produced Monopoly boards for British POWs in Germany, which included hidden maps and compasses to aid escapes. One group of intrepid escapees tunnelled for eighteen months only to come up underneath a hotel, and had to pay £200 because it was on Regent Strasse.

With the advent of the First World War, the Leeds Rifles were

formed and it was they who played that game of football against German troops in no-man’s land on Christmas Day 1914. However, the spirit of the game was spoiled when the German centre forward executed a superb diving header and then ran off with the ball stuck on his spike.

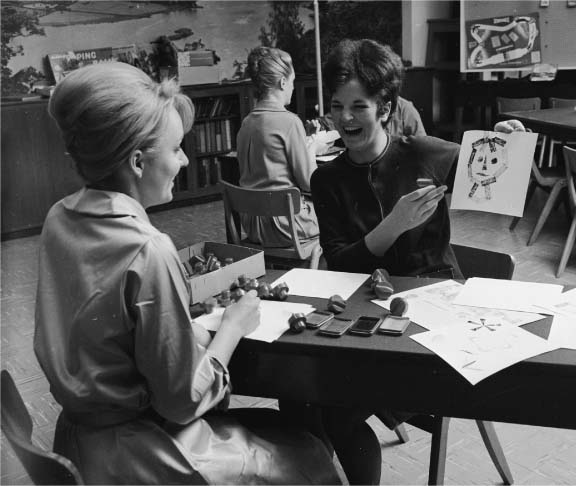

The West Yorkshire Police crack forensics department put together a photofit picture of a notorious criminal based on extensive eye-witness statements

T

HE

N

ORTH

Y

ORKSHIRE

spa town of Harrogate first became famous for the health-giving properties of its sulphur and iron-rich waters. Still operating in the Royal Bath House is its original Turkish Bath and Vichy Shower Jet Room, although the latter had to be closed during the war as the water jets kept changing sides.

In the early 19th Century, Harrogate quickly became popular with the Royal Family. And, as it was then the fashion to copy the habits of royalty, the town was soon overrun with visitors who went there to marry their cousins.

In the years leading up to the First World War, Harrogate saw many holiday visits by the Imperial Russian Royal Family, and indeed, when revolution broke out, they requested asylum there. However, a campaign led by the Daily Mail ensured they were refused, on the grounds there was no real evidence they were under any threat at home.

During the Blitz, many government offices were moved to Harrogate from London. It was amazing how far a building would travel when the Luftwaffe scored a direct hit.

There are also local connections with Admiral Lord Nelson, whose chaplain gave up the sea to become a vicar in Harrogate. Interest in the Reverend Doctor Alexander Scott was revived recently when his family sold some furniture, which historians

realised had come from Nelson’s flagship, when they spotted a small ad that read: ‘For Sale – One Armchair’.

It’s recorded that Lord Byron wrote his poem entitled ‘To A Beautiful Quaker’ while on a trip to Harrogate in 1806, after noticing a beautiful girl in a black robe. The poem begins:

Sweet girl! Though only once we met,

That meeting I shall ne’er forget;

And though we ne’er may meet again,

Remembrance will thy form retain.

Lost for many years, a poem in reply was recently unearthed in the Harrogate Library archive. It reads:

Sweet Lord Byron you flatter me so

But to your offer of love, I must say ‘No’.

For I am the vicar and aged eighty-four,

And I think you’ve been at the laudanum once more.

A famous son of nearby Knaresborough was the 18th Century map-maker and road surveyor ‘Blind Jack’ Metcalfe, who designed the Great North Road. In no time it had stage coaches coming all the way north from London to Penzance.

Other famous names associated with this part of the world include that of Dracula. Bram Stoker, the novelist and keen sportsman, based his character on a Whitby man whom he admired as Yorkshire’s opening bat.

In 1926, mystery surrounded Agatha Christie, who was discovered staying at Harrogate’s Old Swan Hotel eleven days after disappearing from her home. She had become distressed after learning her husband had got a young woman pregnant,

although in his defence he claimed it was the policeman who did it.

The town has a significant American population, who staff the top secret monitoring station at Menwith Hill. This has resulted in Harrogate’s unusual traffic system, where the Americans drive on the right, the British drive on the left and the 4×4s drive anywhere they bloody well like.

Harrogate plays host to the world’s largest annual crime writing festival. Generously sponsored by Theakstons (brewers of the strongest northern ales) this year’s winning entry was an intriguing thriller, even if no one can actually remember who wrote it. They think it might have been the bloke with his underpants on his head.

This year saw Harrogate’s 58th International Christmas and Toy Fair. The event was opened by the town’s Mayor, but he immediately burst into tears and complained it wasn’t the one he wanted.

LYTTELTON’S BRITAIN

LYTTELTON’S BRITAIN  ENGLAND

ENGLANDTHE NORTH-EAST