Lyttelton's Britain (21 page)

Read Lyttelton's Britain Online

Authors: Iain Pattinson

S

HEFFIELD

is a fine city whose history is inextricably linked with steel. The first recorded reference to steel products is found in the works of Chaucer, who mentions the famous ‘Sheffield twittel’, an ancestor of the modern penknife. With a super-sharp blade and immensely strong retracting spring, Chaucer describes its constant use by a pilgrim, one ‘Edwin the Fingerless’.

In the reign of Elizabeth I, Sheffield was chosen to supply sets of silver plate for her household. In those days, the term ‘cutlery’ meant only spoons, which explains the derivation of Her Majesty’s exclamation to staff, which to this day is used to begin all Royal feasts: ‘Oi! Where’s my fork ’n’ knife?’

Prominently displayed in the city centre is the Wilkinson Memorial, dedicated to Sheffield’s most famous razor manufacturer. During the city’s annual Safety Blade Festival, revellers flock there to partake in the custom of decorating the statue’s face, by sticking tiny pieces of tissue to it.

Behind the Memorial lies the National Museum of Shaving Requisites, where visitors can inspect a large collection of traditional shaving brushes, or stroll in the grounds, where they’ll find, shivering, Europe’s largest domestic herd of bald badgers.

Sheffield is a city rightly proud of its two fine football teams – Wednesday and United. Sheffield Wednesday took its name from the day on which the team played their first ever game, after taking the bus to their original ground just outside the town. If they hadn’t chosen to go by First Mainline, they would have been called Sheffield Tuesday Afternoon FC.

Sheffield boasts Europe’s largest public lavatory, designed by the French architect, Jean-Claude de Pissoire

Legendary results savoured by Sheffield football fans to this day, include Manchester United losing two-nil; Manchester United going down three-nil; and Manchester United being thrashed six-nil. None of these results had anything to do with either Sheffield team, but they are certainly great to remember.

For centuries, the city’s name has been found on knives the

globe over, and in recognition of this achievement, the City Fathers erected a sign that reads: ‘Welcome to Sheffield, home of the world’s finest cutlery’. Not to be outdone, the nearby Peak District Council posted a sign that reads: ‘Welcome to Bakewell, birthplace of the world’s greatest tarts.’

Because of its metal-working industry, the area is responsible for providing many common surnames, and at one time Sheffield boasted more ‘Smiths’ than anywhere else in England, until the title was taken one weekend by a cheap hotel in Brighton.

Sheffield is well known for

The Full Monty

, which was filmed on location there. When the producers called for extras for the club scenes, they were amazed by the number of local women who were eager to grab the smaller parts.

Famous celebrities born in Sheffield include Michael Palin (whose name is derived from ‘plannisher’, someone who finished metal by hand), Sean Bean (whose family were ‘banders’ or craftsmen that made barrel hoops by hand) and Joe Cocker (whose family declined to comment).

M

ANCHESTER

is a fine metropolis boasting a wealth of culture and history. According to the Office of National Statistics, Manchester is now Britain’s second city. They don’t say what the first one is.

As the epicentre of the Industrial Revolution, it was there that a phrase was coined that has survived to this day: ‘What happens in Manchester today, happens in the rest of the world tomorrow.’ So, look out rest of the world: tomorrow it’s going to drizzle.

The origins of Manchester lie in a Roman settlement founded by Julius Agricola. His fortified town was called ‘Mamuciam’, meaning ‘a hill shaped like a breast’, as Agricola boasted he liked to name places after whatever he missed from home. However, he kept strangely quiet after founding the town of ‘Ramsbottom’.

It was Agricola who devised modern methods of farming, and it is from him we get the word ‘agriculture’, and also the words ‘get off moy bloody land’.

The town declined in the 5th Century, with the departure of the Romans, when raiding parties from a nearby tribe pillaged building materials from the fine houses, and to this day, marble Doric columns adorn council flats in many parts of Liverpool.

Manchester sank into obscurity for several centuries, until 1028, when King Canute decided to have one of his ten mints

there, the Saxon wars having enforced the introduction of sweet rationing.

In 1485 Manchester figured heavily in the Wars of the Roses. Eventually the dynasties known as the House of Lancaster and the House of York were united by Henry VII, who combined both into the House of Fraser.

Peace reigned until the Civil War, when Royalist troops under Prince Rupert used the city as a base from which to attack nearby towns. He ordered the sacking of Bolton, when the entire town was reduced to a miserable pile of rubble. Later, funds were provided for reconstruction and work is expected to start soon.

The Royalists were soon defeated, however, and Cromwell decided to dissolve Parliament, an act made possible by the habit of constructing public buildings from sugar cubes.

The Manchester we recognise today only really appeared with the Industrial Revolution, when the city’s population was housed in overcrowded slum dwellings. However, sanitary conditions were improved when pipelines were constructed to bring fresh water from the Lake District. These worked well until the 1960s, when one resident ran a bath and discovered Donald Campbell in it.

Manchester became famous for its many mills. There were woollen mills, cotton mills, silk mills, and, with the coming of Italian migrant labour, Europe’s largest pepper mill, which is still in use at the Spaghetti House on Victoria Street.

Throughout the 19th Century, inventors devised many industrial machines in Manchester. There was Arkright’s Cotton Frame and Hargreave’s Eight-Spindle Jenny, and workers were later amazed by Crompton’s Spinning Mule, possibly one of the cruellest circus acts of the age.

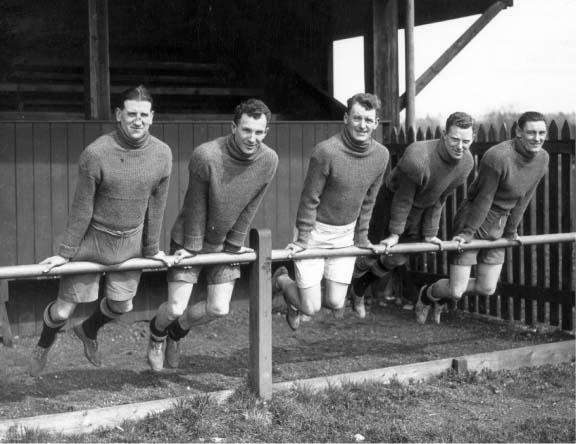

Emergency plumbers improvise when five holes appear in Manchester’s water supply main

In the local cotton mills, weavers were forced to pull strong threads from the machines using their teeth. Compensation was paid for the resultant injury which prevented them pronouncing the letters ‘F’ and ‘T-H’. So, they couldn’t say fairer than that then.

Manchester Cathedral is rightly noted for the Gothic splendour of its architecture. Begun in the Middle Ages, construction work continued on and off for several centuries, before being completed, thanks to a van load of Poles arriving from Gdansk.

Manchester is proud to be home of Chetham’s Library, the

oldest lending library in Britain. It was there that Karl Marx developed his arguments against the proletarian control of capital, and the rights of workers to share in the profit of labour. But the librarian said that despite all that, he was still being fined one and six. And if she caught him drawing in the margins of

Fanny Hill

again it would be half a crown.

The Manchester area has long welcomed immigrant labour from Europe. Salford was known as ‘New Flanders’ because of its Flemish weavers, while Ancoats became known as ‘Little Italy’ because it changed sides three times during World War II.

It was at nearby Trafford Park that Henry Ford’s famous car factory built the massively successful Model ‘T’, a car he boasted you could ‘have in any colour, as long it was black’. As at that time 75 per cent of the world’s vehicles were Model Ts, one can imagine the frustration of trying to find yours when you got back to the car park.

The industrial labour movement was born in Manchester, eventually growing into the Trades Union Congress. So successful was the TUC that it was once honoured by having a cheese biscuit named after it. Their factory workers were served well by the collective bargaining credo of: ‘one out – all out’, but it failed their cricket team miserably.

The women’s movement also started in Manchester, with Emiline Pankhurst and the Suffragettes, who toured with Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas. Starting in 1910, Pankhurst campaigned noisily for women’s rights outside Parliament every day from four o’clock in the afternoon. She would have got there earlier, but she always had a stack of ironing to get through first.

Another noted Mancunian was the businessman and philanthropist,

Jonathan Didcott. On retiring, he sold his business there and left to tend to the poor and homeless in Liverpool, where his good work was said to be ‘tireless’. Just like his car.

Manchester’s first Aerodrome was opened at Trafford Park in 1911, where visitors could take pleasure trips in a novel form of aircraft powered by gas. These weren’t a success, as in windy weather the pilot kept going out.

Manchester’s Arndale Centre is already Britain’s largest city-centre shopping mall, but there are plans afoot to add space for another 200 outlets, at least three of which aren’t going to be Starbucks.

Also from Manchester was Gordon Hill, the former top division football referee. Beginning in 1958, Mr Hill officiated at over 400 matches. Sadly, he was forced to retire on medical grounds in 1972, when his eyesight suddenly came back.

A fictional name associated with Manchester is Daphne Moon, from the American sitcom

Frasier

. On the programme they frequently mention that Daphne is from Manchester, to overcome the obvious confusion caused by her accent.

Nearby Wilmslow is the upmarket suburb that’s become home to many premier league footballers. However, a recent documentary following the daily lives of their wives and girl-friends had to be abandoned, when the film crew collapsed due to peroxide inhalation.

Since 2002, Manchester has been home to the Northern Imperial War Museum at Salford Quays. In celebration of their first season, the museum presented an exhibition of camouflage techniques and were proud to report that over 2000 visitors a week failed to see it.

Camouflage training in preparation for the liberation of Norway, Catterick Army Camp, 1943

The TV antiques expert David Dickinson spent his formative years in Manchester, where as a young man he dated the girl who became his wife. He said about 1947 and worth fifty quid. Dickinson has since left the area as he says he didn’t like the constant rain. It made him go streaky.