Male Sex Work and Society (21 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Calling Cards

Postcards, also known as “calling cards” (Sanders, 2005, 2006) or “tart cards” (

Wallpaper

, 2009), are a familiar site in phone boxes around central London (Sanders, 2005, 2006), and they make elements of sex work very visible. The cards most often feature images of a provocatively dressed model, who may or may not be the advertiser, with a name, telephone number, location, and a brief description of services offered. Cards also can specify services offered by male-to-female transvestite, transgender, and transsexual (both pre- and post-operative) advertisers without necessarily referring specifically to the gender of the clientele. The cards posted in phone boxes in London, even those near gay bars, most often advertise the services of women for male clients. Some cards do advertise services by men for men, but these are few (Londonist, 2012). However, some men report posting similar advertisements, particularly in gay pubs and bars, which gave M$M visibility in gay spaces.

Wallpaper

, 2009), are a familiar site in phone boxes around central London (Sanders, 2005, 2006), and they make elements of sex work very visible. The cards most often feature images of a provocatively dressed model, who may or may not be the advertiser, with a name, telephone number, location, and a brief description of services offered. Cards also can specify services offered by male-to-female transvestite, transgender, and transsexual (both pre- and post-operative) advertisers without necessarily referring specifically to the gender of the clientele. The cards posted in phone boxes in London, even those near gay bars, most often advertise the services of women for male clients. Some cards do advertise services by men for men, but these are few (Londonist, 2012). However, some men report posting similar advertisements, particularly in gay pubs and bars, which gave M$M visibility in gay spaces.

Brian, now in his forties, started selling sex when he was at college. He describes how he and a friend decided that, since they were broke and liked having lots of sex, it would be a suitable enterprise. They printed and posted some flyers, he said, but “it wasn’t like it is now. We didn’t put them in phone boxes or public places because you didn’t know what kind of ‘crazies’ you’d get.” By posting their cards in gay pubs and clubs, Brian and his friend were able to limit homophobic attention from the public—and the law (the age of consent for sex between men was still 21). On the one hand, these men had to avoid legal and social restrictions on having any sex with men, while on the other they faced the dual stigma of being both “homosexuals” and prostitutes (Koken et al., 2010; Weeks, 1995).

Posting cards at businesses targeting gay men has almost totally disappeared in London in recent years, but it is useful to note the place of these cards in advertising that predates both the Internet and early magazine advertisements. The cards often attracted unwanted attention in the form of curiosity, provocation, bullying, or moralizing. In Britain, the Crime and Police Act of 2001 was in part a national response to conditions in Westminster, where an effort was made to stop sex workers from posting cards in phone boxes. The act makes it illegal to post a calling card with contact details for sex workers who work “indoors”; the young men who still place these cards can face up to five years in prison (Sanders, 2005, 2006). The ads that have replaced the cards target gay spaces in magazines, the Internet, and mobile applications—all spaces where the general public is not likely to be engaged.

Magazines

With advertising … you have to make a lot of decisions. Your advert in

GT

or

QX

you pick one picture. Sometimes I put my army picture in, sometimes I put my cock picture in, sometimes I put a leather picture in, and you really are aware that the guys not looking for the army guy probably aren’t going to pick you that week. (Quinn, 39)

In 1991, a new free magazine called

Boyz

appeared in gay pubs around London. The magazine was aimed at young gay men and offered features on pop culture, products, and services that publishers hoped would interest them, including listing venues and events marketed at gay men, whose advertisements paid for the magazine’s publication and distribution. The earliest editions were modeled on

Jackie

magazine, a British title aimed at teenage girls.

Boyz

offered horoscopes, advice columns about love and sex, and personal contact ads, which included a column titled “Escorts & Masseurs” (see

figure 4.1

). Including escorts and masseurs in a single column raised interesting issues about the distinction (and sometimes lack thereof) between “sex” work and “body” work and blurred the boundaries between what is and is not being offered and what is and is not legal.

Boyz

appeared in gay pubs around London. The magazine was aimed at young gay men and offered features on pop culture, products, and services that publishers hoped would interest them, including listing venues and events marketed at gay men, whose advertisements paid for the magazine’s publication and distribution. The earliest editions were modeled on

Jackie

magazine, a British title aimed at teenage girls.

Boyz

offered horoscopes, advice columns about love and sex, and personal contact ads, which included a column titled “Escorts & Masseurs” (see

figure 4.1

). Including escorts and masseurs in a single column raised interesting issues about the distinction (and sometimes lack thereof) between “sex” work and “body” work and blurred the boundaries between what is and is not being offered and what is and is not legal.

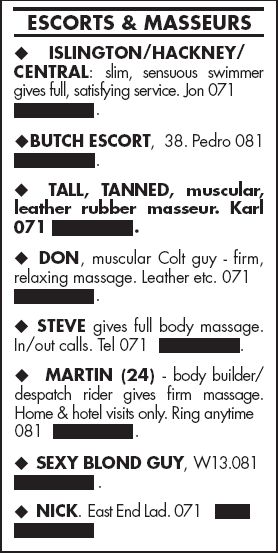

FIGURE 4.1

The first “Escort & Masseurs” section in

Boyz

magazine, August 1, 1991.

Boyz

magazine, August 1, 1991.

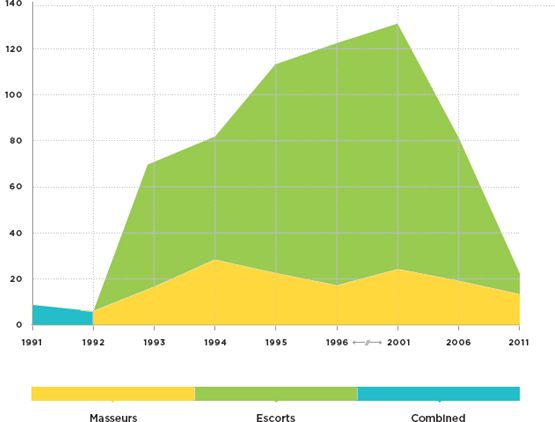

Almost from the start,

Boyz

required anyone wishing to advertise a massage service to prove their qualifications, and within three months the format was changed so there were two columns, one advertising escorts and the other masseurs; the numbers in each column were roughly equal for the next few months. In subsequent years, however, although the number of both escort and masseur advertisements increased dramatically, the number of escort ads was much higher (see

figure 4.2

). For example, in 1996 there were 122 ads for escorts and only 17 for masseurs. This balance was consistent until a change in editorial policy reduced explicit content. In 2010, the management decided to stop running the escort ads altogether, a decision it later reversed.

Boyz

required anyone wishing to advertise a massage service to prove their qualifications, and within three months the format was changed so there were two columns, one advertising escorts and the other masseurs; the numbers in each column were roughly equal for the next few months. In subsequent years, however, although the number of both escort and masseur advertisements increased dramatically, the number of escort ads was much higher (see

figure 4.2

). For example, in 1996 there were 122 ads for escorts and only 17 for masseurs. This balance was consistent until a change in editorial policy reduced explicit content. In 2010, the management decided to stop running the escort ads altogether, a decision it later reversed.

FIGURE 4.2

Number of Advertisements per Issue in Samples of

Boyz

from 1991 to 2011

Boyz

from 1991 to 2011

London is unique in that it offers several free titles targeting the gay scene and two that advertise escort and massage services, which allows for comparisons between titles, controlling for national or regional differences in economics, geography, law, and culture. The variation in ads carried by competing titles (see Deaux & Hanna, 1984) demonstrates that sex and body work advertising and social visibility are influenced by the magazines’ decisions about whether or not to include such ads, and by editorial policies about sexually explicit content. These editorial decisions have an impact on the choices M$M make about how to spend their advertising money.

The emergence of online advertising has also directly affected the number of advertisements placed in magazines. M$M advertisers report having more “editorial” and “creative” control of their advertisements, lower costs, and greater exposure in terms of both duration and geographic reach. Having more control means M$M can use a responsive marketing strategy that can vary within one period, whereas a print campaign is rigidly fixed. M$M, aware of their return on investment, make careful decisions about how to spend their marketing budgets, and print media face increasing competition for ads from online media (Cane, 2009). Equally important is the cost of buying ads, which M$M must consider when evaluating their advertising choices:

Gaydar is just the most accessible … I spoke to another guy who’s an escort and he says he gets the most work from Gaydar, and it’s the cheapest. So as long as I’m getting enough work through Gaydar, I’ll just stay with that—no need to go for something else because the

QX

ads are quite expensive and this guy was saying that he doesn’t get that much work from the

QX

ads. (Kirk, 24)

New Media

Whereas the 1990s saw a dramatic increase in the number of M$M using print media to contact potential clients, the 2000s were the decade when the Internet became a significant medium. The first web address to be included in an escort ad in

Boyz

magazine appeared in 1999, alongside the usual contact telephone numbers, names, and photographs. The descriptions in some of the ads started to get shorter, perhaps because so much more information about the advertiser was available online. As personal use of the Internet became more common, M$M began to use it for advertising. Examples from 2001 show that some advertisers provided links to their own web addresses or to profiles on other websites (e.g.,

www.independent-escorts.com

). By 2004, the magazines were adapting and expanding their business models to include web addresses devoted not only to their titles but to M$M advertising (e.g.,

www.boyzescorts.com

), which they promoted in the M$M sections of their magazines.

Boyz

magazine appeared in 1999, alongside the usual contact telephone numbers, names, and photographs. The descriptions in some of the ads started to get shorter, perhaps because so much more information about the advertiser was available online. As personal use of the Internet became more common, M$M began to use it for advertising. Examples from 2001 show that some advertisers provided links to their own web addresses or to profiles on other websites (e.g.,

www.independent-escorts.com

). By 2004, the magazines were adapting and expanding their business models to include web addresses devoted not only to their titles but to M$M advertising (e.g.,

www.boyzescorts.com

), which they promoted in the M$M sections of their magazines.

Magazines like

GT

have begun to offer online advertising bundled with the purchase of print ad space. The magazine’s escorts home page (GTescorts.co.uk) displays a welcome message, an ad for an escort agency, and a small number of “featured” escorts. As in the print media, M$M online advertising has become a part of the consumable gay scene even to the casual observer, social consumer, or “accidental tourist,” and it forms part of the backdrop to how life for gay men is constructed, represented, and reconstructed.

GT

have begun to offer online advertising bundled with the purchase of print ad space. The magazine’s escorts home page (GTescorts.co.uk) displays a welcome message, an ad for an escort agency, and a small number of “featured” escorts. As in the print media, M$M online advertising has become a part of the consumable gay scene even to the casual observer, social consumer, or “accidental tourist,” and it forms part of the backdrop to how life for gay men is constructed, represented, and reconstructed.

Websites like

Rentboy.com

operate similarly to the GTescorts site, but without a parent magazine. Rentboy hosts profiles for paying advertisers and offers free access to the profiles, which include photographs, telephone numbers, rates, services offered, and, where the advertiser has consented, a mapped location. Enhanced features are offered to users who sign up for membership. Users can search for advertisers by rates charged, sexual practices (positions, safe sex, tastes/fetishes/specialties), and physical features (race, build, body hair, cock size, and foreskin).

Rentboy.com

, which promotes itself as “the world’s largest male escort website,” has marketed aggressively in certain regions in recent years, using print ads, gay scene magazine editorials, and tie-ins with “dance party” or night club events called Hustlaball. The Hustlaball brand is becoming well known on the gay scene, although

Rentboy.com

faces competition from other brands in local markets such as

Sleepyboy.com

, which had almost twice as many M$M listings in London as Rentboy. The sites also generate revenue by selling banner ads that link them to other businesses in the wider sex industry, such as sex-toy and fetish-clothing retailers, as well as their own related businesses (like

Gay Times

magazine and the Hustlaball events). More recently, banner ads for mainstream products and services have appeared with M$M commercial profiles on sites like

Gaydar.net

.

Rentboy.com

operate similarly to the GTescorts site, but without a parent magazine. Rentboy hosts profiles for paying advertisers and offers free access to the profiles, which include photographs, telephone numbers, rates, services offered, and, where the advertiser has consented, a mapped location. Enhanced features are offered to users who sign up for membership. Users can search for advertisers by rates charged, sexual practices (positions, safe sex, tastes/fetishes/specialties), and physical features (race, build, body hair, cock size, and foreskin).

Rentboy.com

, which promotes itself as “the world’s largest male escort website,” has marketed aggressively in certain regions in recent years, using print ads, gay scene magazine editorials, and tie-ins with “dance party” or night club events called Hustlaball. The Hustlaball brand is becoming well known on the gay scene, although

Rentboy.com

faces competition from other brands in local markets such as

Sleepyboy.com

, which had almost twice as many M$M listings in London as Rentboy. The sites also generate revenue by selling banner ads that link them to other businesses in the wider sex industry, such as sex-toy and fetish-clothing retailers, as well as their own related businesses (like

Gay Times

magazine and the Hustlaball events). More recently, banner ads for mainstream products and services have appeared with M$M commercial profiles on sites like

Gaydar.net

.

The Social Networking Site as a Virtual Escort Agency

Before Facebook became an international phenomenon, social networking sites like

Gay.com

and

Gaydar.co.uk

were widely used by gay and bisexual men, sometimes for sex (real or virtual), sometimes for more urbane exchanges. Early interfaces for social networking sites allowed users to log in by creating a “handle”—a name or pseudonym that identified them, perhaps by name, age, or interest, and kept them anonymous (Livia, 2002; Mowlabocus, 2010a). Men wishing to indicate their interest in compensatory exchanges sometimes used signs (e.g., certain words, or symbols like the dollar sign) that flagged their financial interest (e.g., “generousdaddy” or “hot$tuff69”). Users also could add a brief description of themselves, often exaggerated, and/or a description of who or what they were seeking. A whole system of signs and codes came to be understood by users who adapted to restrictions of the interface, such as the number of characters, much as previous generations had with classified print ads (Cocks, 2009). The coded signs allowed them to “work around” the staff who moderated the chat rooms.

Gay.com

and

Gaydar.co.uk

were widely used by gay and bisexual men, sometimes for sex (real or virtual), sometimes for more urbane exchanges. Early interfaces for social networking sites allowed users to log in by creating a “handle”—a name or pseudonym that identified them, perhaps by name, age, or interest, and kept them anonymous (Livia, 2002; Mowlabocus, 2010a). Men wishing to indicate their interest in compensatory exchanges sometimes used signs (e.g., certain words, or symbols like the dollar sign) that flagged their financial interest (e.g., “generousdaddy” or “hot$tuff69”). Users also could add a brief description of themselves, often exaggerated, and/or a description of who or what they were seeking. A whole system of signs and codes came to be understood by users who adapted to restrictions of the interface, such as the number of characters, much as previous generations had with classified print ads (Cocks, 2009). The coded signs allowed them to “work around” the staff who moderated the chat rooms.

It is clear the Internet has extended the commercialization of social-sexual exchange. While U.S.-based sites like

Manhunt.net

abide by state laws that prohibit prostitution (see Weitzer, 2009, 2010), sites regulated by British laws allow commercial transactions but charge a premium for the privilege. The personal and commercial profiles are nearly identical, except the latter include the word “commercial” and personal ads are more likely to be written in the first-person singular (I’m looking for …), whereas commercial ads are more likely to address the audience directly (Call me!) or to include the audience in the narrative (We’ll both be naked for the massage …).

Manhunt.net

abide by state laws that prohibit prostitution (see Weitzer, 2009, 2010), sites regulated by British laws allow commercial transactions but charge a premium for the privilege. The personal and commercial profiles are nearly identical, except the latter include the word “commercial” and personal ads are more likely to be written in the first-person singular (I’m looking for …), whereas commercial ads are more likely to address the audience directly (Call me!) or to include the audience in the narrative (We’ll both be naked for the massage …).

Other books

The Winemaker by Noah Gordon

Only Trick by Jewel E. Ann

Sheikh's Stand In by Sophia Lynn

Meet Me By the Kama Sutra (Regular Sex Issue 4) by Kitty French

Forget Me Not by Goodmore, Jade

The Judge and the Gypsy by Sandra Chastain

Foreigner: (10th Anniversary Edition) by C. J. Cherryh

Alpha Rising by G.L. Douglas

Prey Drive by James White, Wrath