Male Sex Work and Society (18 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

My Own Private Idaho

works similarly to interpolate and rework history as a part of its narrative. In one scene, a cowboy walks into an adult bookstore lined with porn magazines. As the fluorescent bulbs wrapped in pink gel flicker in the seedy, overpacked store, the camera tracks along the magazines, all of which have men on the cover. The camera finally lands on one called

Male Call

, and Scott, wearing a cowboy hat, his naked torso and unbuttoned pants made visible, adorns the cover. The magazine cover reads, “

HOMO ON THE RANGE

.” By utilizing the trope of the cowboy and recoding it within gay culture, Van Sant works to explode the mythology of American masculinity that is “inextricably bound to the image of the cowboy” (Kauffman, 1998, p. 108). As Scott explains his dreams of being a male model, he begins to have a conversation with Mike, who is the cover boy of another magazine,

G-String

, which is on the rack above Scott.

works similarly to interpolate and rework history as a part of its narrative. In one scene, a cowboy walks into an adult bookstore lined with porn magazines. As the fluorescent bulbs wrapped in pink gel flicker in the seedy, overpacked store, the camera tracks along the magazines, all of which have men on the cover. The camera finally lands on one called

Male Call

, and Scott, wearing a cowboy hat, his naked torso and unbuttoned pants made visible, adorns the cover. The magazine cover reads, “

HOMO ON THE RANGE

.” By utilizing the trope of the cowboy and recoding it within gay culture, Van Sant works to explode the mythology of American masculinity that is “inextricably bound to the image of the cowboy” (Kauffman, 1998, p. 108). As Scott explains his dreams of being a male model, he begins to have a conversation with Mike, who is the cover boy of another magazine,

G-String

, which is on the rack above Scott.

In the cover photo, Mike is wearing a white loincloth, his body draped over a vertical wooden pole in a position that recalls popular renderings of the Jesus figure. This posing of Mike has resulted in numerous critics deeming the cover “G-String Jesus” and noting that Mike’s pose “[evokes] the crucifixion” (Breight, 1997, pp. 307-308). The rack of magazine covers combines past and present in a way that “unites Rome, Renaissance England and modern America in a bizarre politico-sexual triad” (pp. 307-308)—a notion that the caption on Mike’s magazine, “

GO DOWN ON HISTORY

,” reinforces.

GO DOWN ON HISTORY

,” reinforces.

Both Scott and Mike (especially as portrayed by their magazine covers) draw on types of men that are summoned time and time again in the visual memory of heteronormative culture. The biblical reference to which Mike’s cover alludes, with his hands fixed up above his head and his nude body leaning backward (ribs protruding), recalls, recodes, and sexualizes the image of the nude body of Christ for homosexual consumption. Not only do these images of Mike and Scott suggest the homosexual potential in traditional icons, they make an explicit link between the male body, homosexuality, history, and male sex work.

New Queer Cinema did much more for the representation of the male sex worker than simply allowing him to be gay without being pathologized; it allowed him to be queer, and it suggested that he always had been. These films exhibit a notion of the queer body that, according to Michele Aaron (2004), sees queerness as

represent[ing] the resistance to, primarily, the normative codes of gender and sexual expression—that masculine men sleep with feminine women—but also to the restrictive potential of gay and lesbian sexuality—that only men sleep with men, and women with women. In this way, queer, as a critical concept, encompasses the non-fixity of gender expression and the non-fixity of both straight and gay sexuality. (p. 5)

Whereas one would assume that all male sex workers (even

American Gigolo

’s strongly heterosexual Julian) would exist outside of heteronormativity and would, therefore, on some level be considered “queer” under Aaron’s definition, pre-NQC cinematic representations of male sex workers (especially in

American Gigolo

and

Midnight Cowboy

) depict a world where male sex worker protagonists are as far from a notion of queer as possible. The most revolutionary element of NQC in relation to the depiction of male sex workers, then, is that the characters of films such as

My Own Private Idaho

and

The Living End

are not simply gay gigolos and they are not merely inversions of the traditionally acceptable male sex worker attempting to provide a positive image of a type of homosexual: they are queer individuals in a way that the protagonists of earlier films could never be.

American Gigolo

’s strongly heterosexual Julian) would exist outside of heteronormativity and would, therefore, on some level be considered “queer” under Aaron’s definition, pre-NQC cinematic representations of male sex workers (especially in

American Gigolo

and

Midnight Cowboy

) depict a world where male sex worker protagonists are as far from a notion of queer as possible. The most revolutionary element of NQC in relation to the depiction of male sex workers, then, is that the characters of films such as

My Own Private Idaho

and

The Living End

are not simply gay gigolos and they are not merely inversions of the traditionally acceptable male sex worker attempting to provide a positive image of a type of homosexual: they are queer individuals in a way that the protagonists of earlier films could never be.

The liberation and aggression with which these NQC films approached their subject matter, however, was not without controversy. When Araki described his work as not having “this propagandistic ‘It’s great to be gay’ outlook” in a 1992 interview in

The Village Voice

(Chua, 1992, p. 64), Adam Mars-Jones (1993), in a review for

The Independent

, saw this break from the desire for positive representation as a poor decision, given the timing of the AIDS crisis. “More than anything,” writes Mars-Jones, “it has been the catastrophe of AIDS, and the urgency of the despair it has brought with it, that has sparked ‘queer’ politics, and put patience out of fashion,” but, ultimately, “the AIDS crisis is a poor moment to pick quarrels” (p. 16).

The Village Voice

(Chua, 1992, p. 64), Adam Mars-Jones (1993), in a review for

The Independent

, saw this break from the desire for positive representation as a poor decision, given the timing of the AIDS crisis. “More than anything,” writes Mars-Jones, “it has been the catastrophe of AIDS, and the urgency of the despair it has brought with it, that has sparked ‘queer’ politics, and put patience out of fashion,” but, ultimately, “the AIDS crisis is a poor moment to pick quarrels” (p. 16).

Interestingly, both Gus Van Sant and Gregg Araki have dealt with the male sex worker in their later films, too, but in strikingly different ways. While Van Sant has gone on to alternate between directing mainstream films for major studios and his own independent works, he has continued to be the executive producer of films that explore queer identity.

15

Incorporating the gritty aesthetic and aggression of the NQC,

Speedway Junky

(Perry, 1999, Van Sant executive producer) follows the story of a young man named Johnny (Jesse Bradford) who wants to become a race car driver as he falls in with a group of hustlers in Las Vegas. Gregg Araki’s

Mysterious Skin

(2004) poses a striking contrast to

Speedway Junky

. The film, which works through a narrative that could have been lifted straight out of an NQC film while appropriating a mainstream aesthetic, is about two teen boys, one of whom is a gay hustler, who are struggling to piece together their lives after their baseball coach had sex with them.

15

Incorporating the gritty aesthetic and aggression of the NQC,

Speedway Junky

(Perry, 1999, Van Sant executive producer) follows the story of a young man named Johnny (Jesse Bradford) who wants to become a race car driver as he falls in with a group of hustlers in Las Vegas. Gregg Araki’s

Mysterious Skin

(2004) poses a striking contrast to

Speedway Junky

. The film, which works through a narrative that could have been lifted straight out of an NQC film while appropriating a mainstream aesthetic, is about two teen boys, one of whom is a gay hustler, who are struggling to piece together their lives after their baseball coach had sex with them.

Post-NQC, the use of the character type of the male sex worker has flourished and become dramatically fractured. While major studio productions

Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo

(Mitchell, 1999) and

The Wedding Date

(Kilner, 2005) work to sanitize the gigolo, maintaining strict hetero-sexuality and presenting homosexual sex work as abject,

Mandragora

(Grodecki, 1997),

Speedway Junky, Lola und Bilidikid

(Ataman, 1999),

L.I.E

. (Michael Cuesta, 2001),

Sonny

(Cage, 2002),

Mysterious Skin

,

Breakfast on Pluto

(Jordan, 2005), and

Boy Culture

(Brocka, 2006) all have worked to push the male sex worker in a variety of other directions.

Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo

(Mitchell, 1999) and

The Wedding Date

(Kilner, 2005) work to sanitize the gigolo, maintaining strict hetero-sexuality and presenting homosexual sex work as abject,

Mandragora

(Grodecki, 1997),

Speedway Junky, Lola und Bilidikid

(Ataman, 1999),

L.I.E

. (Michael Cuesta, 2001),

Sonny

(Cage, 2002),

Mysterious Skin

,

Breakfast on Pluto

(Jordan, 2005), and

Boy Culture

(Brocka, 2006) all have worked to push the male sex worker in a variety of other directions.

Mandragora

and

Lola und Bilidikid

both grapple with male sex work in a way that echoes the work of the NQC. Robin Griffiths (2008) sees a strong parallel between the aims of

Mandragora

, which follows the rise and fall of a teenage hustler in Czechoslovakia, and the aims of the NQC. “Grodecki,” writes Griffiths, “was just as ground breaking in his unwavering yet ambivalent commitment to destabilize and subvert the heteronormatively inclined moral narratives, imagery and subjectivities that governed the more established tropes of Czech cinema and cultural production: confronting its entrenched stereotypes, assumptions and taboos even as he problematically re-inscribed them” (p. 139). While

Mandragora

ends tragically and ultimately works to reinforce notions of sex work as perverse, it deals with the AIDS crisis in a very visceral way.

and

Lola und Bilidikid

both grapple with male sex work in a way that echoes the work of the NQC. Robin Griffiths (2008) sees a strong parallel between the aims of

Mandragora

, which follows the rise and fall of a teenage hustler in Czechoslovakia, and the aims of the NQC. “Grodecki,” writes Griffiths, “was just as ground breaking in his unwavering yet ambivalent commitment to destabilize and subvert the heteronormatively inclined moral narratives, imagery and subjectivities that governed the more established tropes of Czech cinema and cultural production: confronting its entrenched stereotypes, assumptions and taboos even as he problematically re-inscribed them” (p. 139). While

Mandragora

ends tragically and ultimately works to reinforce notions of sex work as perverse, it deals with the AIDS crisis in a very visceral way.

In a scene of

Mandragora

in which Malek (Miroslav Caslavka), the film’s protagonist, and his friend David (David Svec) hire two female prostitutes to have sex, Malek is asked if he would like to have sex with or without a condom (there is a price difference). “You’re not afraid of AIDS?” Malek asks. “We’ve all got it anyway,” replies his companion. Where AIDS (and disease more generally) is never a concern for

Deuce Bigalow

or

The Wedding Date

’s Nick (Dermont Mulroney) and where

The Living End

’s Luke and Joe, in the height of the AIDS crisis, have been diagnosed with a death sentence,

Mandragora

’s sex workers are always already implicated in the AIDS crisis as a simple fact of their profession. While issues of abject morality foreground many of the films that, either explicitly or implicitly, deal with male sex work pre-AIDS, films since the AIDS outbreak have fractured, dealing both with the moral implications of sex work and, frequently, concerns about health and disease. Where the dirty, run-down spaces of

Midnight Cowboy

historically symbolized abjection in regards to cinematic representations of male sex work, the bodies of the hustlers in

Mandragora

and

The Living End

have become a new site of concern.

Mandragora

in which Malek (Miroslav Caslavka), the film’s protagonist, and his friend David (David Svec) hire two female prostitutes to have sex, Malek is asked if he would like to have sex with or without a condom (there is a price difference). “You’re not afraid of AIDS?” Malek asks. “We’ve all got it anyway,” replies his companion. Where AIDS (and disease more generally) is never a concern for

Deuce Bigalow

or

The Wedding Date

’s Nick (Dermont Mulroney) and where

The Living End

’s Luke and Joe, in the height of the AIDS crisis, have been diagnosed with a death sentence,

Mandragora

’s sex workers are always already implicated in the AIDS crisis as a simple fact of their profession. While issues of abject morality foreground many of the films that, either explicitly or implicitly, deal with male sex work pre-AIDS, films since the AIDS outbreak have fractured, dealing both with the moral implications of sex work and, frequently, concerns about health and disease. Where the dirty, run-down spaces of

Midnight Cowboy

historically symbolized abjection in regards to cinematic representations of male sex work, the bodies of the hustlers in

Mandragora

and

The Living End

have become a new site of concern.

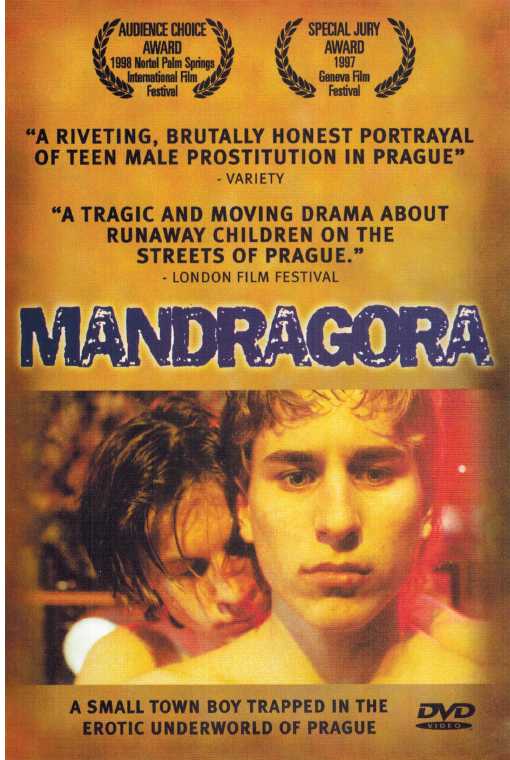

FIGURE 3.4

Mandragora

’s sex workers are always implicated in the AIDS crisis as a simple fact of their profession during the period of time in which the film takes place.

’s sex workers are always implicated in the AIDS crisis as a simple fact of their profession during the period of time in which the film takes place.

References

Aaron, M. (2004). New queer cinema: An introduction. In M. Aaron (Ed.),

New queer cinema: A critical reader

. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

New queer cinema: A critical reader

. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

Aggleton, P. (Ed). (1999).

Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and HIV/AIDS

. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and HIV/AIDS

. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Benshoff, H. M., & Griffin, S. (2006).

Queer images: A history of gay and lesbian film in America

. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Queer images: A history of gay and lesbian film in America

. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Breight, C. (1997). Elizabethan World Pictures. In J. J. Joughin, (Ed.),

Shakespeare and national culture

. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press.

Shakespeare and national culture

. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press.

Burston, P. (1995). Just a gigolo? Narcissism, nelyism and the “new man” theme. In P. Burston & C. Richardson (Eds.),

A queer romance: Lesbians, gay men, and popular culture

. London: Routledge.

A queer romance: Lesbians, gay men, and popular culture

. London: Routledge.

Casper, D. (2011).

Hollywood film, 1963-1976: Years of revolution and reaction

. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hollywood film, 1963-1976: Years of revolution and reaction

. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

Chua, L. (1992, August 25). Low and inside.

The Village Voice

, p. 64.

The Village Voice

, p. 64.

Cresap, K. (2004).

Pop trickster fool: Warhol preforms naivete

. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Pop trickster fool: Warhol preforms naivete

. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Davis, G. (2002). Gregg Araki. In Y. Tasker (Ed.),

Fifty contemporary filmmakers

. London: Routledge.

Fifty contemporary filmmakers

. London: Routledge.

D’Lugo, M. (2006).

Pedro Almodóvar

. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Pedro Almodóvar

. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Epps, B., & Kakoudaki, D. (2009).

All about Almodovar

. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

All about Almodovar

. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Escoffier, J. (2009).

Bigger than life: The history of gay porn cinema from beefcake to hardco

re. Philadelphia: Running.

Bigger than life: The history of gay porn cinema from beefcake to hardco

re. Philadelphia: Running.

Farber, M., & Patterson, P. (1975, November/December). Fassbinder.

Film Comment

, pp. 5-6.

Film Comment

, pp. 5-6.

Flexner, A. (1914).

Prostitution in Europe

. New York: Century.

Prostitution in Europe

. New York: Century.

Flowers, R. B. (2011).

Prostitution in the Digital Age: Selling sex from the suite to the street

. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Prostitution in the Digital Age: Selling sex from the suite to the street

. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Griffiths, R. (2008). Bodies without borders? Queer cinema and sexuality after the fall. In R. Griffiths (Ed.),

Queer cinema in Europe

. Bristol, England: Intellect.

Queer cinema in Europe

. Bristol, England: Intellect.

Hadden, M. (1916).

Slavery of prostitution: A plea for emancipation

. New York: MacMillan.

Slavery of prostitution: A plea for emancipation

. New York: MacMillan.

Hart, K.-P. R. (2010).

Images for a generation doomed: The films and career of Gregg Araki

. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Images for a generation doomed: The films and career of Gregg Araki

. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Kauffman, L. S. (1998).

Bad girls and sick boys: Fantasies in contemporary art and culture

. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bad girls and sick boys: Fantasies in contemporary art and culture

. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kemp, T. (1936).

Prostitution: An investigation of its causes, especially with regard to hereditary factors

. Copenhagen, Denmark: Levin & Munksgaard.

Prostitution: An investigation of its causes, especially with regard to hereditary factors

. Copenhagen, Denmark: Levin & Munksgaard.

Kuzniar, A. (2000).

The queer German cinema

. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

The queer German cinema

. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lang, R. (2002).

Masculine interest: Homoerotics in Hollywood film

. New York: Columbia University Press.

Masculine interest: Homoerotics in Hollywood film

. New York: Columbia University Press.

League of Nations. (1943).

Prevention of prostitution

. Geneva: Author.

Prevention of prostitution

. Geneva: Author.

Malcolm, D. (1993, February 11). Films: The road to hell.

The Guardian

.

The Guardian

.

Other books

Dirty Laundry by Rhys Ford

Molten Gold by Elizabeth Lapthorne

A Rake’s Guide to Seduction by Caroline Linden

Ask Me Something (The Something Series Book 2) by Aubrey Bondurant

Light My Fire by Redford, Jodi

Valdez Is Coming by Elmore Leonard

Loki by Keira Montclair

A Sister's Secret by Mary Jane Staples

Freeze Frame by Heidi Ayarbe

Lady Churchill's Rosebud Wristlet No. 20 by Gavin J. Grant, Kelly Link