Male Sex Work and Society (14 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

For their part, many working-class youths approached prostitution as a simple means to an end—for food, amusements, shelter, and more. Interested adolescents openly shared information with each other regarding who was a client and what exactly they wanted. Working-class parents did not necessarily approve of this behavior, and at times they took action against the adult clients, particularly if a relationship was ongoing and deemed to be exploitative. Yet parents sometimes knew about and condoned their sons’ activities, being in need of the additional income that their sons brought in. Working-class boys were generally expected to contribute to the household economy, often taking dangerous jobs in the process (indeed, children had a rate of workplace-related accidents that was three times that of adults), and these facts helped shift the moral calculus in favor of toleration.

With the ongoing rise and stigmatization of “homosexuality,” fewer and fewer “normally identified” men were willing to engage in sex with other men. This shift could be seen in the shifting vernacular of the day:

The term “trade” originally referred to the customer of a fairy prostitute, a meaning analogous to and derived from its usage in the slang of female prostitutes; by the 1910s, it referred to any “straight” man who responded to a gay man’s advances. As one fairy put it in 1919, a man was trade if he “would stand to have “queer” persons fool around [with] him in any way, shape or manner.” “Trade” was also increasingly used in the middle third of the century to refer to straight-identified men who worked as prostitutes serving gay-identified men, reversing the dynamic of economic exchange and desire implied by the original meaning. (Chauncey, 1994, pp. 69-70)

Nevertheless, many working-class “straight” men remained willing to sell sex to “gay” men. During the Depression years, when many men were pushed into prostitution by economic want, straight-acting men effectively overwhelmed the old effeminate style of streetwalking, joining the soldier prostitute strolls and pushing the remaining fairy prostitutes to more marginalized locations. This transition, which has been identified as occurring in New York City in 1932, marks the final passing of widespread straight cruising of fairy men. Although fairy prostitutes continued to exist, and although some straight men even cruised the new generation of young but “normal” youth, gay men now dominated the client base for the first time.

Despite their willingness to have sex with men, for some men, ideas concerning gay identity made certain acts more acceptable than others. Most “normally identified” working-class men and adolescents would only take “insertive” roles lest they be seen (and start to see themselves) as “fairies.” Although some working-class youth were willing to submit to “feminizing” sexual acts (e.g., being sodomized) in the late Victorian period, as gay identity became more accepted, the sexual encounters involved nothing more than being orally or manually stimulated by the gay man, or perhaps mutual masturbation at the most. The new restrictions on sexual behavior were not always happily welcomed by clients, and one gay man who cruised both young working-class men and soldiers during the 1920s complained that “those normal young men who request for themselves this form of amusement [oral sex] never offer it in return” (Ackerly, 1968, p. 130). If the rise of gay culture put limits on what most straight men were willing to do, however, it also led queer-identified men to sell sex to each other for the first time. This pattern represented only a small minority, however, and the men selling sex within this new scene were discreetly normative in appearance, not effeminate.

Although the growing dominance of the homosexual ideology reduced the number of “normal” men who were willing to actively seek out fairies as clients, it eventually cut down on the number of working-class men who were willing to act as trade, even for a price. As the increasing use of the term “trade” to refer more directly to monied exchanges suggests, the pool of available straight men slowly became restricted to undisguised cash for sex transactions with specialists: “street hustlers.” If previously a wide cross-section of the straight male working class had been willing to trade sex for money, by mid-century only the most marginalized were willing to deal with the stigma associated with gay identity. The literature concerning male prostitution in the 1950s, 1960s, and even into the early 1970s, is replete with stories of “deviants” or “hoodlum types” who engaged prostitution as a means of obtaining spending money. Gone for the most part were the “barracks prostitution” and the widespread participation of many working-class youth: the messenger boys and newspaper sellers so common in Victorian-era scandals. In its place remained mostly those “delinquent” youths who, while they generally lived at home and had their survival needs taken care of, nevertheless were unable or unwilling to secure work in the formal labor market and used the cash they obtained to finance their recreational activities, including, for a growing minority, to support drug habits. In the larger cities, these youths were supplemented by unemployed men who relied on prostitution for their survival, by a limited population of straight-identified bodybuilders who posed in muscle magazines and occasionally sold sex to gay men on the side, and by a small but slowly increasing number of gay men who followed the 1920s pattern of selling sex to gay men while remaining somewhat discreet. An even smaller number of cross-dressing fairies also continued, but the field was now clearly dominated by the teenaged “delinquent.” Full-time professional hustlers existed only in the larger cities, but even moderate-sized towns such as Boise, Idaho, with a population of approximately 50,000 in the 1950s, had a male street hustling scene then, made up mostly of “delinquent” youth.

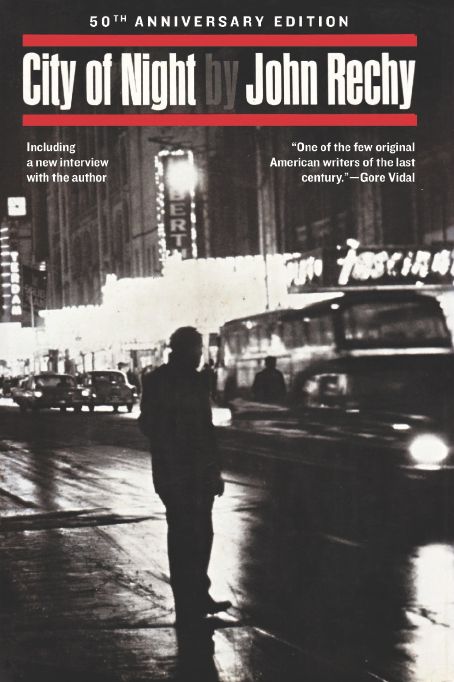

FIGURE 2.2

Cover of

City of Night

, John Rechy’s groundbreaking novel about male sex work.

City of Night

, John Rechy’s groundbreaking novel about male sex work.

The ascendancy of the sexological ideology of homosexuality dramatically accelerated with the rise of “gay liberation.” By the late 1960s and early 1970s, gay writers were forcefully questioning the “straightness” of any man who had sex of any sort with another man. “As for the hustler,” wrote one observer, “most gays look down upon him for maintaining that he’s really straight” (Hunt, 1977, p. 136). The rise of gay liberation made it still more difficult for men to engage in same-sex sexual relations without being forced to take on the onus of the homosexual identification. The older paradigm in which working-class men experienced sexual pleasure with “fairy” men and maintained their normative status became virtually untenable with the increasing visibility of gay life. Most male street prostitutes came to occupy only very marginal spaces within the gay social world and did not generally participate in the gay political struggle. Quite the contrary, street hustlers often felt quite hostile to gay liberation, seeing in it a movement that excluded them and their concerns.

Yet, if the ideology of homosexuality brought difficult personal challenges for some hustlers, for others the rise of gay liberation led toward an increasing acceptance of gay or bisexual self-identity. One of the first openly gay authors of this period was, in fact, a formerly straight-identified hustler who wrote more or less autobiographically of his life. John Rechy’s first book,

City of Night

(1963), remained on bestseller lists for months and is now considered a gay classic. It precisely documented the central character’s confrontation with his own inclinations toward homosexuality. Ironically, many of those who worked on the street were unable to claim their gay status openly as their gay clientele still frequently preferred straight “trade.” “I have on occasion made a definite statement [proclaiming myself gay],” wrote Rechy, “and the person has lost interest in me” (1978/1974, p. 266).

City of Night

(1963), remained on bestseller lists for months and is now considered a gay classic. It precisely documented the central character’s confrontation with his own inclinations toward homosexuality. Ironically, many of those who worked on the street were unable to claim their gay status openly as their gay clientele still frequently preferred straight “trade.” “I have on occasion made a definite statement [proclaiming myself gay],” wrote Rechy, “and the person has lost interest in me” (1978/1974, p. 266).

Although a preference for straight (or semistraight) trade was manifest on the streets in the late 1960s, other sexual markets began to open up in which the clients displayed no such tendency. Gay men began selling sex to one another in much larger numbers, mostly working off the street through escort agencies and ads. Although some gay clients had sought gay workers before the 1970s, the gay liberation era marked the first time that most gay men began to buy sex from other gay men, rather than from straight outsiders who lived the bulk of their lives outside the gay world. The new relationship between client and prostitute produced new sexual practices. Clients in the late 19

th

century had only sought to act as “tops” with youths, but gay men could now pay to take a “dominant” role with adult men. Clients calling agencies often sought much more than to give oral satisfaction to the hustler, seeking “versatile” partners whom they could anally penetrate, workers willing to participate in three-ways with another worker, or others who would help create sexual fantasy scenes via costumes. The resulting possibilities transformed the work dynamics even for those on the street who sought to continue in the prior, “inserter-only” modality, as greater pressure was placed on them to perform a greater variety of sexual acts.

th

century had only sought to act as “tops” with youths, but gay men could now pay to take a “dominant” role with adult men. Clients calling agencies often sought much more than to give oral satisfaction to the hustler, seeking “versatile” partners whom they could anally penetrate, workers willing to participate in three-ways with another worker, or others who would help create sexual fantasy scenes via costumes. The resulting possibilities transformed the work dynamics even for those on the street who sought to continue in the prior, “inserter-only” modality, as greater pressure was placed on them to perform a greater variety of sexual acts.

The shifts in male prostitution associated with gay liberation led to a significant reworking of the meanings associated with prostitution. Although the act represented a simple means of supplementing one’s income or allowance for a previous generation of “delinquents,” for the first time it became a possible means of affirming one’s sexual identity. Indeed, for a brief time, the gay-identified prostitute came to represent the new spirit of gay liberation. Just as earlier writers used the figure of the prostitute male to illuminate aspects of “homosexuality” more generally, a new generation of gay writers took to the image of the hustler to rework the theme. For many in the newly emerging gay world, the gay prostitute symbolized a life option that embraced sexual pleasure and avoided any necessity for hiding one’s sexual identity. Pornographic collections of short stories, such as

Stud

(1996),

My Brother the Hustler

(1970a), and

San Francisco Hustler

(1970b), all by Samuel Steward [under the name Phil Andros], stood at the forefront of a shift in gay writing, transforming it from what has been called “a literature of guilt and apology” into one of “political defiance and celebration of sexual difference” (Hall, 1988).

Stud

(1996),

My Brother the Hustler

(1970a), and

San Francisco Hustler

(1970b), all by Samuel Steward [under the name Phil Andros], stood at the forefront of a shift in gay writing, transforming it from what has been called “a literature of guilt and apology” into one of “political defiance and celebration of sexual difference” (Hall, 1988).

References

Ackerly, J. R. (1968).

My father and myself

. New York: Coward-McCann.

My father and myself

. New York: Coward-McCann.

Andros, P. (1966).

Stud

. Boston: Alyson.

Stud

. Boston: Alyson.

Andros, P. (1970a).

My brother, the hustler

. San Francisco: Gay Parisian Press.

My brother, the hustler

. San Francisco: Gay Parisian Press.

Andros, P. (1970b).

San Francisco hustler

. San Francisco: Gay Parisian Press.

San Francisco hustler

. San Francisco: Gay Parisian Press.

Chauncey, G. (1994).

Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay world, 1890-1940

. New York: Harper Collins.

Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay world, 1890-1940

. New York: Harper Collins.

Hall, R. (1988, June 19). Gay fiction comes home.

New York Times

. Available at

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html.res=940DE3D91330F93AA25755COA96E948260

New York Times

. Available at

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html.res=940DE3D91330F93AA25755COA96E948260

Hirschfeld, M. (2000).

The homosexuality of men and women

(M. Lombardi-Nash, Trans.). Amherst, NY: Promethius Books. (Original work published 1913)

The homosexuality of men and women

(M. Lombardi-Nash, Trans.). Amherst, NY: Promethius Books. (Original work published 1913)

Hunt, M. (1977).

Gay: What you should know about homosexuality

. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Gay: What you should know about homosexuality

. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Leyland, W. (Ed.). (1978).

Winston Leyland interviews John Rechy: Gay Sunshine interviews

. San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press. Original work published in

Gay Sunshine

, November/December 1974.

Winston Leyland interviews John Rechy: Gay Sunshine interviews

. San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press. Original work published in

Gay Sunshine

, November/December 1974.

Rechy, J. (1963).

City of night

. New York: Grove Press.

City of night

. New York: Grove Press.

What stands out for us in this chapter is the way the images, understandings, and explanations of male sex work through cinematic representations have changed dramatically over time. This evolution highlights the important point sociologists make that subjective definitions and perceptions of a phenomenon play a central role in shaping cultural images. This chapter demonstrates that the male hustler is essentially an outdated cultural image that is no longer relevant in understanding the often dynamic and complex encounters of the male sex worker’s world. While the representation of these encounters in modern films remains largely unaltered, the settings and the language have evolved to reflect the changing definitions of gender and sexualities. In the early films discussed in this chapter, the sex work encounter frequently took place in a public place, such as a restroom, cinema, or seedy motel. We find this ironic, as these are public places, but the phenomenon of male sex work was not yet part of the public discussion or chitchat

.

.

Viewing

Midnight Cowboy

(1969) was often a grim experience. Late 1960s New York, where the movie takes place, was an alienating and ruthless environment characterized by poverty and urban decay. Hustling is presented in this film as a demoralizing, sleazy, and violent practice. More recent films present a very different picture of male sex work. For example, in the romantic comedy

Going Down in La-La Land

(2012), a young man goes to Hollywood to act in gay porn movies and becomes an escort. Ultimately he falls in love with a closeted famous TV actor, who in turn falls in love with him. Who would have considered it possible that a romantic comedy about a male sex worker would emerge as a relatively successful popular movie? This contrasts sharply with some of the grim earlier films Russell Sheaffer discusses in this chapter

.

Midnight Cowboy

(1969) was often a grim experience. Late 1960s New York, where the movie takes place, was an alienating and ruthless environment characterized by poverty and urban decay. Hustling is presented in this film as a demoralizing, sleazy, and violent practice. More recent films present a very different picture of male sex work. For example, in the romantic comedy

Going Down in La-La Land

(2012), a young man goes to Hollywood to act in gay porn movies and becomes an escort. Ultimately he falls in love with a closeted famous TV actor, who in turn falls in love with him. Who would have considered it possible that a romantic comedy about a male sex worker would emerge as a relatively successful popular movie? This contrasts sharply with some of the grim earlier films Russell Sheaffer discusses in this chapter

.

Other books

The BACHELORETTE Project (The Project: LESLEE Series) by Anthony, Tami

Unlikely Friendships : 47 Remarkable Stories From the Animal Kingdom by Holland, Jennifer S.

Fallen Series 04 - Rapture by Kate, Lauren

AnyasDragons by Gabriella Bradley

High-Stakes Affair by Gail Barrett

Every Kind of Heaven by Jillian Hart

Bound in Blood by J. P. Bowie

Absolute Hush by Sara Banerji

Worlds in Collision by Judith Reeves-Stevens

Powdered Murder by A. Gardner