Male Sex Work and Society (15 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

| Representations of Male Sex Work in Film | |

RUSSELL SHEAFFER |

Histories of Male Hustlers

In his 676-page

History of Prostitution

, published by the Eugenics Publishing Company in 1939, William Sanger (a medical doctor from New York) discusses male prostttution in only one short paragraph. Sanger writes:

History of Prostitution

, published by the Eugenics Publishing Company in 1939, William Sanger (a medical doctor from New York) discusses male prostttution in only one short paragraph. Sanger writes:

This hasty classification of the Roman prostitutes would be incomplete without some notice, however brief, of male prostitutes. Fortunately, the progress of good morals has divested this repulsive theme of its importance; the object of this work can be obtained without entering into details on a branch of the subject which in this country is not likely to require fresh legislative notice. But the reader would form an imperfect idea of the state of morals at Rome were he left in ignorance of the fact that the number of male prostitutes was probably fully as large as that of females. (p. 70)

This near negation of the mere existence of the male sex worker is a stream that runs through many writings on and histories of prostitution that appeared during the early 20th century in the United States.

1

In Sanger’s work, male prostitution, understood to be a “repulsive” act that is fundamentally linked to the Greeks and Romans, is said to have been eradicated by society’s “good” morals.

1

In Sanger’s work, male prostitution, understood to be a “repulsive” act that is fundamentally linked to the Greeks and Romans, is said to have been eradicated by society’s “good” morals.

Occasionally, an author such as George Scott (1936), in his

History of Prostitution from Antiquity to the Present Day

, discusses male prostitution at some level of historical depth (although even this “depth” is still only 11 pages of a 231-page book).

2

Scott’s history, published two years before Sanger’s, chronicles the male prostitute’s role in society via biblical writings and thus is also highly influenced by a moral hierarchy, in that, for Scott, the bulk of male prostitution is fundamentally linked to homosexuality and savagery. Unlike many of his contemporaries, however, Scott repeatedly attempts to qualify and nuance his discussion of male prostitution in relation to male homosexuality, breaking down the demand for male prostitutes into subcategories.

3

In much the same way Sanger discusses male prostitution as something that must be named but is relatively unimportant, Scott brings in a discussion of the gigolo, a male prostitute who is not a homosexual and whose sex acts, therefore, hold “no criminality … and no perverse practices” (p. 186). Scott’s discussion of the gigolo, who has sex exclusively with “sex-starved women” (p. 187) for pay, is simply a note in passing; he is a prostitute, yes, but only by definition, and he is certainly not characterized by “perversion,” as is the homosexual male prostitute.

History of Prostitution from Antiquity to the Present Day

, discusses male prostitution at some level of historical depth (although even this “depth” is still only 11 pages of a 231-page book).

2

Scott’s history, published two years before Sanger’s, chronicles the male prostitute’s role in society via biblical writings and thus is also highly influenced by a moral hierarchy, in that, for Scott, the bulk of male prostitution is fundamentally linked to homosexuality and savagery. Unlike many of his contemporaries, however, Scott repeatedly attempts to qualify and nuance his discussion of male prostitution in relation to male homosexuality, breaking down the demand for male prostitutes into subcategories.

3

In much the same way Sanger discusses male prostitution as something that must be named but is relatively unimportant, Scott brings in a discussion of the gigolo, a male prostitute who is not a homosexual and whose sex acts, therefore, hold “no criminality … and no perverse practices” (p. 186). Scott’s discussion of the gigolo, who has sex exclusively with “sex-starved women” (p. 187) for pay, is simply a note in passing; he is a prostitute, yes, but only by definition, and he is certainly not characterized by “perversion,” as is the homosexual male prostitute.

Two things become strikingly apparent from these early histories of prostitution: (1) that male sex workers have been severely under-discussed in histories of prostitution; and (2) when male sex workers are written about historically, the “problem” of male sex work is fundamentally linked to the “problem” of homosexuality. These two elements are crucial to understanding the dominant representations of the male sex worker in American cinema before the emergence of the New Queer Cinema movement in the early 1990s.

Male Hustlers in Cinema

While films such as

Midnight Cowboy

(Schlesinger, 1969) and

American Gigolo

(Schrader, 1980) presented some of the first widely accessible images of the male prostitute in American cinema,

4

the characters of these films fall exclusively within the realm of the gigolo. These gigolos openly acknowledge and embrace the idea that homosexual male prostitution is abject in a fundamentally different way than heterosexual male prostitution, capitulating to homosexual sex only when their circumstances become dire.

Midnight Cowboy

(Schlesinger, 1969) and

American Gigolo

(Schrader, 1980) presented some of the first widely accessible images of the male prostitute in American cinema,

4

the characters of these films fall exclusively within the realm of the gigolo. These gigolos openly acknowledge and embrace the idea that homosexual male prostitution is abject in a fundamentally different way than heterosexual male prostitution, capitulating to homosexual sex only when their circumstances become dire.

New Queer Cinema, informed by the AIDS crisis and the U.S. government’s poor response to it in the late 1980s, provided films that presented new ways of seeing gay characters—including the male sex worker. Two films in particular,

The Living End

(Araki, 1992) and

My Own Private Idaho

(Van Sant 1991), both deemed a part of the New Queer Cinema movement by B. Ruby Rich (2004) in her canonical essay, “New Queer Cinema,” participate in a significant discourse that has worked to question historical understandings of the male sex worker in a way that marks a drastic shift from the films of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

The Living End

(Araki, 1992) and

My Own Private Idaho

(Van Sant 1991), both deemed a part of the New Queer Cinema movement by B. Ruby Rich (2004) in her canonical essay, “New Queer Cinema,” participate in a significant discourse that has worked to question historical understandings of the male sex worker in a way that marks a drastic shift from the films of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

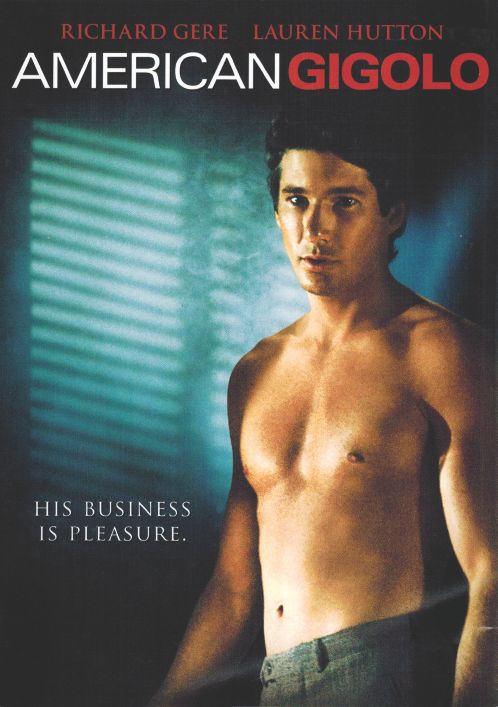

FIGURE 3.1

American Gigolo

presented one of the first widely accessible images in American cinema of a male prostitute who serves women. The main character nearly turns to homosexual sex, but only when his circumstances become dire. Reproduced with permission from Paramount Pictures.

presented one of the first widely accessible images in American cinema of a male prostitute who serves women. The main character nearly turns to homosexual sex, but only when his circumstances become dire. Reproduced with permission from Paramount Pictures.

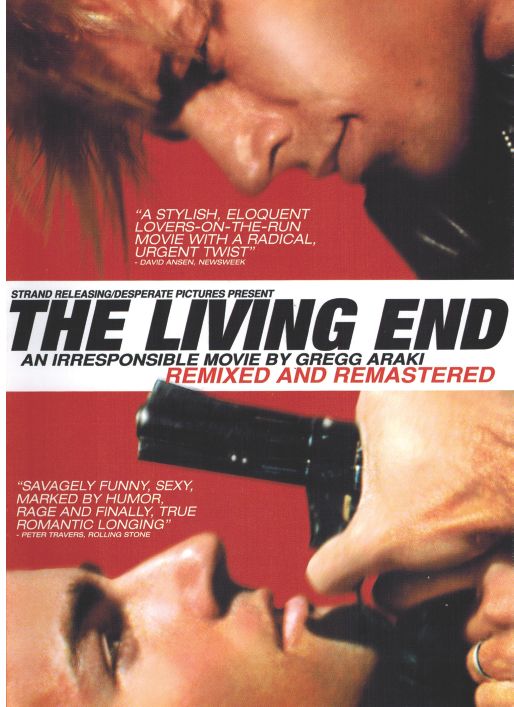

FIGURE 3.2

The Living End

, which follows the road-trip adventure of a spontaneously violent, macho, and newly diagnosed HIV-positive hustler and his lover, is described as a film of “almost unbearable intimacy.” Reproduced with permission from Strand Releasing.

, which follows the road-trip adventure of a spontaneously violent, macho, and newly diagnosed HIV-positive hustler and his lover, is described as a film of “almost unbearable intimacy.” Reproduced with permission from Strand Releasing.

To a certain extent, the male hustler was a character type in cinema decades before

Midnight Cowboy

, but not in the way the term has come to be defined. “Hustler” currently applies most often to men who “[engage] in homosexual behavior” for pay (Steward, 1991, p. xi). However, if we understand the term “hustler” as someone who hustles and is “looking for something, and who sooner or later finds himself pretending to be something he isn’t, or thinks he isn’t, or wishes he were, or doesn’t realize he wishes he were” (Lang, 2002, p. 249), we raise the possibility that a hustler may be hustling for any number of things—clothes, a place to stay, or money, for example—and may exchange other services, like time or company, without explicitly selling sex. In this way, characters who may, for all intents and purposes, be gigolos could be passed off in code-era Hollywood as “kept men.” The hustler as a kept man applies to any number of characters from 1940s-1950s Hollywood, such as Joe Gillis (played by William Holden) in Billy Wilder’s

Sunset Boulevard

(1950) or Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly) in Vincente Minnelli’s

An American in Paris

(1951).

Midnight Cowboy

, but not in the way the term has come to be defined. “Hustler” currently applies most often to men who “[engage] in homosexual behavior” for pay (Steward, 1991, p. xi). However, if we understand the term “hustler” as someone who hustles and is “looking for something, and who sooner or later finds himself pretending to be something he isn’t, or thinks he isn’t, or wishes he were, or doesn’t realize he wishes he were” (Lang, 2002, p. 249), we raise the possibility that a hustler may be hustling for any number of things—clothes, a place to stay, or money, for example—and may exchange other services, like time or company, without explicitly selling sex. In this way, characters who may, for all intents and purposes, be gigolos could be passed off in code-era Hollywood as “kept men.” The hustler as a kept man applies to any number of characters from 1940s-1950s Hollywood, such as Joe Gillis (played by William Holden) in Billy Wilder’s

Sunset Boulevard

(1950) or Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly) in Vincente Minnelli’s

An American in Paris

(1951).

Sunset Boulevard

provides a particularly interesting example because it toys rather explicitly with the content restrictions of the Motion Picture Production Code. On the surface,

Sunset Boulevard

figures Joe as a kept man who—in Ed Sikov’s (1998) words—“survives by smoothly humoring his patron” (p. 297) by writing for her, dancing with her, and living in her home. Even though the film never shows a sex act between its characters, the implicit notion that Joe also has sex with his benefactress is made relatively clear, as various commentators have noted. Sikov, for example, explains that Joe survives “first by writing a part for [Norma] in a movie that will never be made, and then by making love to her” (p. 297). Joe explains his relationship with Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) to his young love interest, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), by saying, “It’s lonely here, so she got herself a companion. A very simple set-up: an older woman who is well to do, a younger man who is not doing too well. Can you figure it out yourself?” Even though the ban on the topic of prostitution was lifted from studio pictures in 1956 (Pennington, 2007, p. 110),

Sunset Boulevard

could never have made explicit any sexual relationship between Norma and Joe, since on-screen sex was still unacceptable under the code. Instead, the film asks the viewer to connect the dots, essentially posing the same question to the audience that Joe asks Betty: “Can you figure it out yourself?”

provides a particularly interesting example because it toys rather explicitly with the content restrictions of the Motion Picture Production Code. On the surface,

Sunset Boulevard

figures Joe as a kept man who—in Ed Sikov’s (1998) words—“survives by smoothly humoring his patron” (p. 297) by writing for her, dancing with her, and living in her home. Even though the film never shows a sex act between its characters, the implicit notion that Joe also has sex with his benefactress is made relatively clear, as various commentators have noted. Sikov, for example, explains that Joe survives “first by writing a part for [Norma] in a movie that will never be made, and then by making love to her” (p. 297). Joe explains his relationship with Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) to his young love interest, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), by saying, “It’s lonely here, so she got herself a companion. A very simple set-up: an older woman who is well to do, a younger man who is not doing too well. Can you figure it out yourself?” Even though the ban on the topic of prostitution was lifted from studio pictures in 1956 (Pennington, 2007, p. 110),

Sunset Boulevard

could never have made explicit any sexual relationship between Norma and Joe, since on-screen sex was still unacceptable under the code. Instead, the film asks the viewer to connect the dots, essentially posing the same question to the audience that Joe asks Betty: “Can you figure it out yourself?”

Tennessee Williams’s

The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone

(Quintero, 1961) and

Sweet Bird of Youth

(Brooks, 1962) posed interesting complications relative to the code’s strict guidelines for Hollywood films. Both

Mrs. Stone

and

Sweet Bird

feature characters who, with only a small a mount of interpretive license, are gigolos satisfying older women in order to make a living.

Sweet Bird of Youth

, much like

Sunset Boulevard

, follows a young man, Chance (Paul Newman), who is trying to make it in Hollywood by “caring for” an older actress. Where

Sunset Boulevard

asks its audience to fill in the gaps,

Sweet Bird

makes the sex that has occurred between Chance and his benefactress, Alexandra Del Lago (Geraldine Page), clear. After a heated discussion between Chance and Alexandra, Alexandra walks to bed, saying, “I have only one way to forget the things that I don’t want to remember, and that way is by making love. It’s the only dependable distraction and I need that distraction right now. In the morning we’ll talk about what you want and what you need.” Chance responds, “Aren’t you ashamed a little?” “Yes, aren’t you?” replies Alexandra. Although it seems that Chance has avoided sex for compensation up until this point, he ultimately succumbs to an act that makes him feel ashamed.

The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone

(Quintero, 1961) and

Sweet Bird of Youth

(Brooks, 1962) posed interesting complications relative to the code’s strict guidelines for Hollywood films. Both

Mrs. Stone

and

Sweet Bird

feature characters who, with only a small a mount of interpretive license, are gigolos satisfying older women in order to make a living.

Sweet Bird of Youth

, much like

Sunset Boulevard

, follows a young man, Chance (Paul Newman), who is trying to make it in Hollywood by “caring for” an older actress. Where

Sunset Boulevard

asks its audience to fill in the gaps,

Sweet Bird

makes the sex that has occurred between Chance and his benefactress, Alexandra Del Lago (Geraldine Page), clear. After a heated discussion between Chance and Alexandra, Alexandra walks to bed, saying, “I have only one way to forget the things that I don’t want to remember, and that way is by making love. It’s the only dependable distraction and I need that distraction right now. In the morning we’ll talk about what you want and what you need.” Chance responds, “Aren’t you ashamed a little?” “Yes, aren’t you?” replies Alexandra. Although it seems that Chance has avoided sex for compensation up until this point, he ultimately succumbs to an act that makes him feel ashamed.

Challenging Censorship

The work of American playwright Tennessee Williams often pressed the Production Code Administration (PCA) beyond any previous films in terms of adult themes. R. Barton Palmer (1998) cites

A Streetcar Named Desire

(Kazan, 1951) as a turning point in this respect. Palmer notes that, shortly before

A Streetcar Named Desire, Bicycle Thief

(de Sica, 1949) had been released in the United States without the approval of the PCA—a huge blow to the administration, in that the film went on to be “defiantly successful” at the box office. “After the Bicycle Thief embarrassment,” writes Palmer, “Breen [head of the PCA] could ill afford another public incident that suggested his office was narrow-minded in its opposition to modern art. Williams’s play, after all, had won the Pulitzer Prize” (p. 218). Even though these films were able to deal with male sex work, they sprung from the world of Broadway and literature, from a cultural form that “[catered] to a minority, elite culture.” This is exactly the kind of culture, however, that the PCA was beginning to fear censoring around the time of

Streetcar

. It is because of this precedent that, a decade later, Hollywood art films

The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone

and

Sweet Bird of Youth

, both penned by the critically acclaimed Williams, could be produced by major studios.

5

A Streetcar Named Desire

(Kazan, 1951) as a turning point in this respect. Palmer notes that, shortly before

A Streetcar Named Desire, Bicycle Thief

(de Sica, 1949) had been released in the United States without the approval of the PCA—a huge blow to the administration, in that the film went on to be “defiantly successful” at the box office. “After the Bicycle Thief embarrassment,” writes Palmer, “Breen [head of the PCA] could ill afford another public incident that suggested his office was narrow-minded in its opposition to modern art. Williams’s play, after all, had won the Pulitzer Prize” (p. 218). Even though these films were able to deal with male sex work, they sprung from the world of Broadway and literature, from a cultural form that “[catered] to a minority, elite culture.” This is exactly the kind of culture, however, that the PCA was beginning to fear censoring around the time of

Streetcar

. It is because of this precedent that, a decade later, Hollywood art films

The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone

and

Sweet Bird of Youth

, both penned by the critically acclaimed Williams, could be produced by major studios.

5

Whereas

Sunset Boulevard

is unable to fully articulate the work that Joe Gillis is doing and the characters in

Sweet Bird of Youth

saw sex work as something of which to be ashamed, Andy Warhol’s

My Hustler

(1965) and Peter Emmanuel Goldman’s

Echoes of Silence

(1967) were some of the first American films to make their characters’ sex work an explicit and celebrated part of their story. Often discussed in relation to (and as a part of) the “highbrow underground art films” (Thomas, 2000, p. 69) of the 1960s New York avant-garde scene, these films broke ground in the filmic representation of the male sex worker. Working outside of Hollywood code-era restrictions and screening outside of mainstream venues,

6

art films were free to experiment with both content and form in ways that exceeded the freedom of the Hollywood studios.

My Hustler

, for example, is roughly an hour long and comprised of only two shots—one on a Fire Island beach, and the other in the bathroom of one of its characters. During the shot on the beach, Warhol spends 30 minutes focused on the reclined body of Paul (Paul America), a hustler from “Dial-a-Hustler” who has been hired to service Ed (Ed Hood) on Fire Island. The camera makes rough, choppy pans between Paul’s body on the beach and a conversation occurring between Ed, Joe (Joseph Campbell), and Genevieve (Genevieve Charbon) in Ed’s beachfront home. The second shot of the film, which also lasts approximately 30 minutes, takes place in a private bathroom. In this shot, Joe and Paul take showers, shave, and get dressed while discussing hustling as an occupation (Joe is a semiretired hustler himself).

Sunset Boulevard

is unable to fully articulate the work that Joe Gillis is doing and the characters in

Sweet Bird of Youth

saw sex work as something of which to be ashamed, Andy Warhol’s

My Hustler

(1965) and Peter Emmanuel Goldman’s

Echoes of Silence

(1967) were some of the first American films to make their characters’ sex work an explicit and celebrated part of their story. Often discussed in relation to (and as a part of) the “highbrow underground art films” (Thomas, 2000, p. 69) of the 1960s New York avant-garde scene, these films broke ground in the filmic representation of the male sex worker. Working outside of Hollywood code-era restrictions and screening outside of mainstream venues,

6

art films were free to experiment with both content and form in ways that exceeded the freedom of the Hollywood studios.

My Hustler

, for example, is roughly an hour long and comprised of only two shots—one on a Fire Island beach, and the other in the bathroom of one of its characters. During the shot on the beach, Warhol spends 30 minutes focused on the reclined body of Paul (Paul America), a hustler from “Dial-a-Hustler” who has been hired to service Ed (Ed Hood) on Fire Island. The camera makes rough, choppy pans between Paul’s body on the beach and a conversation occurring between Ed, Joe (Joseph Campbell), and Genevieve (Genevieve Charbon) in Ed’s beachfront home. The second shot of the film, which also lasts approximately 30 minutes, takes place in a private bathroom. In this shot, Joe and Paul take showers, shave, and get dressed while discussing hustling as an occupation (Joe is a semiretired hustler himself).

Other books

A Free Life by Ha Jin

Daring to Dream by Sam Bailey

Walk Through the Valley (Psalm 23 Mysteries) by Debbie Viguié

Leap of Faith by Fiona McCallum

Diamond in the Blue: D.I. Simpers Investigates by Phil Kingsman

When We Were Us (Keeping Score, #1) by Tawdra Kandle

The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas fils

Ravishing the Heiress by Sherry Thomas

Lilia's Secret by Erina Reddan

Allegiance by Timothy Zahn