Male Sex Work and Society (65 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Male sexual services in Latin America are readily available to anyone with an interest and some cash (Hodge, 2001, 2005b; Mitchell, 2010), although not all Latin America countries have legalized sex work. Where sex work is illegal, sex workers are more stigmatized and vulnerable (Aggleton, Parker, & Maluwa, 2003; Arnold & Barling, 2003; Vandepitte et al., 2006). In such countries, sex workers’ rights are not protected, nor are their health needs considered important. Little is known about how sex workers in these contexts navigate their limited work rights or access equitable health services, or social and legal protections. Understanding the intersection between the social and legal contexts of sex work in Latin America is key to addressing health inequities for this group. These socioeconomic inequities may go some way in explaining the commitment of MSWs (or lack thereof) to safe sex practices and health outcomes.

Sexual Health

Safer sex practices are acknowledged as a key to reducing the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs; UNAIDS, 2010). The social context of MSWs is important, as poor social support and financial instability may lead MSWs to engage in unsafe sexual practices with both clients and their partners, such as choosing to forgo condom use in particular situations (Padilla & Castellanos, 2008; Schifter, 1998, 1999). In the Dominican Republic, for example, Padilla and Castellanos (2008) found that some MSWs did not use condoms with regular clients who they felt were trustworthy, or with their steady girlfriend(s). Notably, UNAIDS (2010) reported that MSWs in five Latin America countries used condoms in their interactions with clients between 45 percent and 91 percent of the time. In Mexico, for instance, some did not use condoms in certain situations, despite their awareness of the protective attributes, because they did not like how the condom felt or tasted (Colby, 2003). This is not exclusive to Latin American MSWs, as similar sentiments have been found in many other populations (i.e., Bagnol & Mariano, 2008; Hall, Hogben, Carlton, Liddon, & Koumans, 2008; MacPhail & Campbell, 2001; Serovich, Craft, McDowell, Grafsky, & Andrist, 2009; Sturges et al., 2009). As these studies clearly indicate, being a MSW is a particularly risky profession in terms of the health of both worker and client, and the lack of legal and medical protections exacerbates these risks.

Risky sexual behavior also has been linked to drug use by MSWs. In Sao Paulo, for instance, 50 percent of 520 MSWs studied indicated that they had used cocaine, marijuana, and/or crack within the previous year (Grandi et al., 2000). Clients also may encourage drug use and pay MSWs to use cocaine with them in hotel rooms. Drug and alcohol use is prevalent among Latin America MSWs from low socioeconomic backgrounds, often those who work on the streets (Grandi et al., 2000; Infante et al., 2009; Mariño et al., 2003; Schifter, 1998, 1999). Of concern, then, is the influence that drug and alcohol use may have on the ability of MSWs to assess their risk of contracting STIs, negotiate personal safety, and enforce safer sex practices; exchanging sex for money, drugs, or food is associated with higher incidence of HIV infection (Pando et al., 2003). While recreational drug use is not directly associated with HIV, regular cocaine use is significantly associated with an HIV-positive diagnosis (Pando et al., 2003). Thus, drug use is another risk factor that elevates the health risks of MSWs.

STI and HIV Risk Assessment and Transmission

Although some MSWs are engaging in unsafe sexual activities with clients, both the sex worker and their clients go through a risk assessment process to determine whether or not to use a condom (Caceres, 2002; Padilla & Castellanos, 2008). However, even those who try to be diligent and consistent with their condom use may not always be able to maintain safe sex behaviors (Grandi et al., 2000; Infante et al., 2009), as some MSWs are coerced and others intentionally forgo safe sex practices (Padilla & Castellanos, 2008). In situations where they do not use condoms, some MSWs use strategies they believe will reduce their risk of contracting STIs:

When performing oral sex I might do it correctly at the beginning, but when the client starts enjoying it, I will start talking to him and I will masturbate him. Also when having sexual intercourse I close my legs so that the client’s penis does not reach my anus. Basically he will be fucking my legs. These are strategies for me. (Infante et al., 2009, p. 134)

MSWs in the Dominican Republic indicated that if they had unprotected sex with a client, they did not disclose this information to their girlfriend(s) or suggest they use a condom for fear of being labeled gay or a sex worker; as one 26-year-old MSW commented, “Can you imagine after four years me telling her we’re going to use condoms! What would she think?” (Padilla & Castellanos, 2008, p. 8). In Brazil, between 63 percent and 83 percent of MSWs who engaged in anal sex with their clients (with and/or without a condom) did not use condoms with their steady partners (Grandi et al., 2000).

Conversely, in an Argentinean study by Disogra (2012), a minority of participants (3.7 percent) mentioned having insertive anal sex without a condom. Only one MSW said he was was willing to perform receptive anal sex without a condom, whereas the majority (63.3 percent) said they had receptive anal sex with a condom. Disogra (see part three of this chapter) also noted that condom use during a commercial sex encounter decreased significantly when the MSW perceived that the client’s penis was large. Although this may be because neither the MSW nor the client had large enough condoms, this raises important questions about the resources and education available to Latin America MSWs in support of safe sex practices.

Considering the risk assessment process MSWs undertake to justify unprotected sexual activity with their clients and the reality of the statistics, they may not be as informed about STIs as they should be or perceive themselves to be (Infante et al., 2009; Mariño et al., 2003; Padilla & Castellanos, 2008). Unfortunately, sex worker education, empowerment, and services are limited and/or sparse in many Latin American countries. This inequitable lack of health services attuned to the needs of sex workers further impedes the ability of MSWs to make safer sex choices, and to negotiate and enforce protective behaviors. Limited access to condoms and to education about safer sex has grave implications for MSWs, their clients, and their steady partners. Awareness about MSWs, the risk of STIs and HIV/AIDS, as well as perceived access to health services, may also be reflected in how MSWs are represented in popular Latin American culture.

Media and Sex Work in Latin America

Since the 1970s, the issue of masculinity and male sexuality in Latin America has been the subject of both academic and popular cultural discussion (see Correa, Jaramillo, & Ucros, 1972). Although academics on the continent contributed to the legitimization of sexual diversity through analyses of its influences, the pathological view of homosexuality remained intact well into the 1990s or even later. In this heteronormative context, the media played an important role in providing a channel through which sexual minorities could present and advocate for their rights. For instance, films like

Strawberry and Chocolate

(1993) from the late Cuban director Tomas Gutiérrez helped spark debate on the subject in Cuba and created a social space that considered the rights of homosexuals. Acceptance and inclusion can also be seen in Argentina, where same-sex marriage was approved in 2010, and in Brazil, Ecuador, Uruguay, and Colombia, where civil unions for same-sex couples were approved in 2011; in 2013, Uruguay and Brazil took the next step and approved same sex marriges.

Strawberry and Chocolate

(1993) from the late Cuban director Tomas Gutiérrez helped spark debate on the subject in Cuba and created a social space that considered the rights of homosexuals. Acceptance and inclusion can also be seen in Argentina, where same-sex marriage was approved in 2010, and in Brazil, Ecuador, Uruguay, and Colombia, where civil unions for same-sex couples were approved in 2011; in 2013, Uruguay and Brazil took the next step and approved same sex marriges.

While sexual diversity is slowly becoming the norm in Latin America, MSWs usually have much less visibility in the media than their female counterparts. From time to time, however, a scandal or other event involving MSWs will attract attention and ignite sensationalist media reporting. To analyze media constructed images of MSWs in Latin America, we present two articles that appeared in

Somos

, an Argentinian political magazine from the 1990s (Guarinoni, 1991; Messi & Girardi, 1991); two movies from the 2000s; and websites that advertise male escorts.

Somos

, an Argentinian political magazine from the 1990s (Guarinoni, 1991; Messi & Girardi, 1991); two movies from the 2000s; and websites that advertise male escorts.

MSWs in Written Media

In the article titled “Taxi boys. La prostitución masculina crece: cómo, cuándo y dónde” (“Taxi boys: Masculine prostitution grows: how, when and where”), which was published in early 1991 in the popular Argentine magazine

Somos

, the authors described a group of MSWs who worked as escorts out of an apartment in Buenos Aires. The workers promoted their services in local newspapers and had a “manager” who answered the telephone and arranged appointments with clients. The article reveals that their monthly income from sex work was between US$1,500 to US$2,000 each; workers who recruited clients on the streets earned much less. The authors also noted that a number of MSWs who worked on the street and homosexuals in the Barrio Norte (an upper-class district in Buenos Aires) had been murdered. In this regard, MSWs who advertised in the press were described as being safer and more expensive than those who worked on the street. The MSWs were described as young men between age 21 and 24, sometimes older if they had established longstanding relationships with clients or if they had a large penis (Messi & Girardi, 1991).

Somos

, the authors described a group of MSWs who worked as escorts out of an apartment in Buenos Aires. The workers promoted their services in local newspapers and had a “manager” who answered the telephone and arranged appointments with clients. The article reveals that their monthly income from sex work was between US$1,500 to US$2,000 each; workers who recruited clients on the streets earned much less. The authors also noted that a number of MSWs who worked on the street and homosexuals in the Barrio Norte (an upper-class district in Buenos Aires) had been murdered. In this regard, MSWs who advertised in the press were described as being safer and more expensive than those who worked on the street. The MSWs were described as young men between age 21 and 24, sometimes older if they had established longstanding relationships with clients or if they had a large penis (Messi & Girardi, 1991).

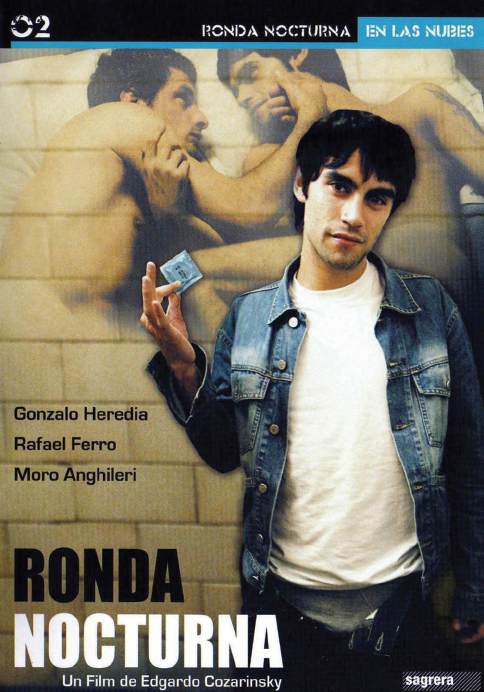

FIGURE 15.1

DVD cover for a Spanish film,

Ronda Nocturna

.

Ronda Nocturna

.

Copyright © Sagera, 2005

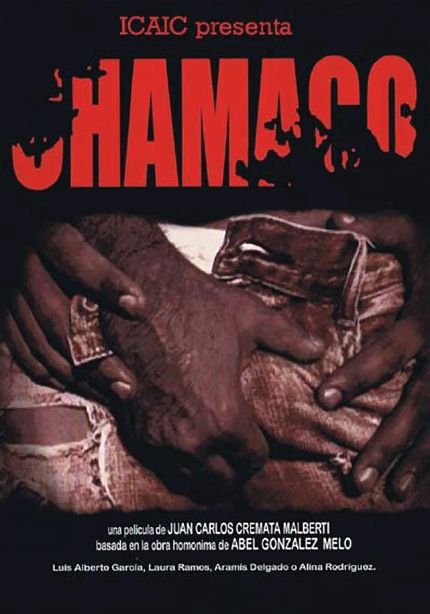

FIGURE 15.2

Poster for the Cuban film,

Chamaco

. Copyright © ICAIC, 2010

Chamaco

. Copyright © ICAIC, 2010

Although MSWs advertised in

Somos

that they provided sexual services to men, women, and couples, the MSWs described in the article saw significantly more male than female clients. In the article, the typical image of the MSW client was an older homosexual man or wealthy woman. This contradicts findings from a more recent study by Disogra, Minichiello, and Mariño (see part three of this chapter), which suggests that MSWs’ clients are primarily heterosexual couples age 35 to 40, women age 20 to 40, and men age 21 to 70; MSW respondents also described many of their clients as married. Sexual services offered ranged from sexual intercourse to group sex, sadomasochism, and voyeurism. Some clients used drugs, particularly cocaine.

Somos

that they provided sexual services to men, women, and couples, the MSWs described in the article saw significantly more male than female clients. In the article, the typical image of the MSW client was an older homosexual man or wealthy woman. This contradicts findings from a more recent study by Disogra, Minichiello, and Mariño (see part three of this chapter), which suggests that MSWs’ clients are primarily heterosexual couples age 35 to 40, women age 20 to 40, and men age 21 to 70; MSW respondents also described many of their clients as married. Sexual services offered ranged from sexual intercourse to group sex, sadomasochism, and voyeurism. Some clients used drugs, particularly cocaine.

The second article in

Somos

indicated that MSWs also worked in women-only nightclubs and presented several pictures of the escorts dancing and undressing in front of their female audience (Guarinoni, 1991). The club patrons were described as “mostly wealthy women.” The two articles included nine pictures, mostly of the escorts at the nightclub, although one showed a male escort picking up a client on the street. He was pictured leaning into the window of an automobile while he negotiated with the potential client. As this brief analysis demonstrates, journalists can construct images of MSWs that may contradict those of the sex workers themselves and are not consistent with ever-changing contexts occuring in the sale and purchase of sex work services.

Somos

indicated that MSWs also worked in women-only nightclubs and presented several pictures of the escorts dancing and undressing in front of their female audience (Guarinoni, 1991). The club patrons were described as “mostly wealthy women.” The two articles included nine pictures, mostly of the escorts at the nightclub, although one showed a male escort picking up a client on the street. He was pictured leaning into the window of an automobile while he negotiated with the potential client. As this brief analysis demonstrates, journalists can construct images of MSWs that may contradict those of the sex workers themselves and are not consistent with ever-changing contexts occuring in the sale and purchase of sex work services.

MSWs in Film

The Argentinean film

Ronda Nocturna

(

Night Watch

) is a story about Victor, a working-class MSW who recruits sex work clients on the street of Buenos Aires and also sells drugs. There is a contrast between the film’s protagonist in the initial scenes of the movie, where he is portrayed as an energetic young man in the company of other MSWs, to the final scenes, where he is portrayed as defeated and rather lonely, thus suggesting that being an MSW is dispiriting work full of chaos and crisis.

Ronda Nocturna

(

Night Watch

) is a story about Victor, a working-class MSW who recruits sex work clients on the street of Buenos Aires and also sells drugs. There is a contrast between the film’s protagonist in the initial scenes of the movie, where he is portrayed as an energetic young man in the company of other MSWs, to the final scenes, where he is portrayed as defeated and rather lonely, thus suggesting that being an MSW is dispiriting work full of chaos and crisis.

Other books

To Have And To Hold: The Wedding Belles Book 1 by Lauren Layne

The Shimmer by David Morrell

Jump the Gun by Zoe Burke

Fighting For You by Noelle, Megan

Scarlett by Ripley, Alexandra

How to Fall by Edith Pearlman

The German Fifth Column in Poland by Aleksandra Miesak Rohde

The Perfect Son by Barbara Claypole White

One Bloody Thing After Another by Joey Comeau

Valkyrie - the Vampire Princess 3 by Pet Torres