Male Sex Work and Society (69 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

| Migrant Male Sex Workers in Germany | |

HEIDE CASTAÑEDA |

It’s a sunny June morning in Berlin’s Schöneberg district as I walk down a shady sidewalk with two young men, Andrei and Georgi. Although the 19-year-olds arrived from Romania just a few months earlier, they had visited Germany many times before. They’re dressed to impress: Andrei’s jeans are fastened in place by a flashy silver belt buckle with the Dolce & Gabbana logo, complemented by black Puma sneakers and a fitted blue T-shirt. As he walks, he nonchalantly eats breakfast, a small package of cookies from the gas station. Georgi is dressed in similar fashion: a sequined Ed Hardy print T-shirt, his spiky gelled black hair in need of a trim. They’re full of “swag”—an English term popular among young Berliners—which seems to belie their current activity: picking up discarded cigarette butts. As we walk, Georgi bends over to collect the butts, which he hands to Andrei. Every four or five steps, he bends over or squats to the ground. They have a system in place: bend, pick up, hand over, walk, bend, pick up, hand over. It takes a keen eye to distinguish which are worth picking up, those that have enough white left behind the brown filter, but they have a good pace going. Before an afternoon nap, they tear open the thin paper and mix the tobacco with a small chunk of hashish. It’s a Friday, so they get some rest before heading to the bars and working until early the next morning.

Andrei and Georgi are part of the growing phenomenon of migrant male sex workers (MSWs) in German cities, a population that remains underexplored by social scientists, despite a long history of male sex work as part of the nation’s erotic landscape (Evans, 2003).

1

In this chapter, I argue that this increase in migrant MSWs is a response to the complementary but contradictory appearance of economic opportunities (freedom of movement across European Union [EU] borders) and constraints (transitional measures restricting migrants’ access to the labor market). A major focus of this chapter is the primary health concerns faced by this population, moving beyond the myopic association between sex work and HIV to contextualize health risks as a result of macro-level processes, including poverty, discrimination, unemployment, lack of housing, inadequate health-care access, and removal from kin support structures through migration. Especially troubling is their lack of access to medical services, reflecting a socio-legal position that resembles that of unauthorized migrants rather than EU citizens. To encourage and maintain the availability of appropriate services for MSWs, it is important to add to the sparse literature on their health status and use of health services.

1

In this chapter, I argue that this increase in migrant MSWs is a response to the complementary but contradictory appearance of economic opportunities (freedom of movement across European Union [EU] borders) and constraints (transitional measures restricting migrants’ access to the labor market). A major focus of this chapter is the primary health concerns faced by this population, moving beyond the myopic association between sex work and HIV to contextualize health risks as a result of macro-level processes, including poverty, discrimination, unemployment, lack of housing, inadequate health-care access, and removal from kin support structures through migration. Especially troubling is their lack of access to medical services, reflecting a socio-legal position that resembles that of unauthorized migrants rather than EU citizens. To encourage and maintain the availability of appropriate services for MSWs, it is important to add to the sparse literature on their health status and use of health services.

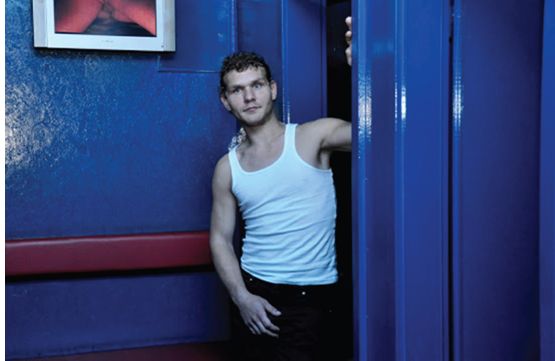

FIGURE 16.1

Still from the award-winning German film

Rentboys

(

Die Jungs vom Bahnhof Zoo

), which describes the lives of male sex workers in Berlin.

Rentboys

(

Die Jungs vom Bahnhof Zoo

), which describes the lives of male sex workers in Berlin.

The lives of MSWs in Berlin are the subject of the award-winning 2011 film

Rent Boys

(German title:

Die Jungs von Bahnhof Zoo

) by director and prominent gay rights activist Rosa von Praunheim. A Berlin organization working with this population reported that the film provides a “relatable picture of life in prostitution and illustrates the experiences of familial, societal, and sexual violence that the boys have traversed,” as well as “exploitation because of inequality, racism, and poverty” (Subway, 2012).

2

Rent Boys

focuses on three young Roma migrants who take up sex work in Germany to escape poverty in their native Romania. The filmmakers follow one of the men, Lionel, back to his home village, where it becomes obvious that migration into sex work is a common, but hushed, strategy adopted by local youth.

Rent Boys

(German title:

Die Jungs von Bahnhof Zoo

) by director and prominent gay rights activist Rosa von Praunheim. A Berlin organization working with this population reported that the film provides a “relatable picture of life in prostitution and illustrates the experiences of familial, societal, and sexual violence that the boys have traversed,” as well as “exploitation because of inequality, racism, and poverty” (Subway, 2012).

2

Rent Boys

focuses on three young Roma migrants who take up sex work in Germany to escape poverty in their native Romania. The filmmakers follow one of the men, Lionel, back to his home village, where it becomes obvious that migration into sex work is a common, but hushed, strategy adopted by local youth.

Indeed, only in recent years have scholars begun to turn their attention to the largely invisible population of migrants who sell sex in a number of host country settings (Agustin, 2006). Contrary to many assumptions, there is a significant demand for male sex workers (Dennis, 2008). However, the men and boys in the global sex trade are almost completely ignored by social service agencies, administrative bodies, the media, and in scholarship. This is matched by “a silence in the literature on how men who are structurally disadvantaged in the global political economy—as gendered beings who are situated within multiple social hierarchies related to race, class, masculinity, and sexuality—are implicated in the patterns of ‘structural violence’ that shape the HIV/AIDS epidemic” (Padilla, 2007, p. xii). Examining structural violence provides an analytic tool for understanding how health and disease are impacted by social inequalities and how political economic systems put particular individuals or groups in situations of extreme vulnerability. The concept of structural vulnerability can extend this analysis to an examination of how a host of mutually reinforcing economic, political, cultural, and psychodynamic insults that dispose individuals and communities toward ill health are embodied (Quesada, Hart, & Bourgois, 2011). MSWs face a lack of economic options, live in precarious social situations, and encounter structures of dependency that may lead them to engage in risky practices associated with the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In much of the existing literature, MSWs are assigned considerably more agency than females, thus framing them as active risk-takers and negating the importance of constrained opportunity (Dennis, 2008). Indeed, despite impressive documentation of associations between structural forces and the prevalent burden of illness, public health interventions continue to focus primarily on changing the micro-behaviors of individuals through educational interventions and models of rational decision making. Furthermore, prevention efforts for this population have been insufficient because specific risks differ from those for female sex workers and require tailored interventions (Allman & Myers, 1999).

This chapter first explores the role of migration as it relates to male sex work, before turning to a description of the German case in particular. Unique to the German situation is not only the fact that prostitution is a legal activity but that these migrant MSWs are not “illegal” because they are EU citizens. However, while permitted to travel across borders, at the time of this study, most were not yet authorized to work in Germany because of transitional measures curbing access to national labor markets. After considering why these young men migrate away from their home countries, including social marginalization and a lack of economic opportunities, I describe their life in a large city, in this case Berlin. The chapter then turns to major health concerns, using a structural vulnerability framework and arguing for a more holistic understanding of the health needs of Germany’s migrant MSWs.

Background: Male Sex Work and Migration

Sex work is defined as any occupation where an individual is hired to provide sexual services in exchange for money and/or other items of value (Minichiello et al., 2001). This characterization views sexual labor as a legitimate means of employment; however, at the same time, it does not preclude the very real occurrence of exploitation. It underscores the need to understand prostitution as labor, rather than making assumptions about individual pathology (Parsons, 2005) or overestimating the role of human trafficking (Agustin, 2006).

Male and transgender sex work remains underresearched, even in the commercial sex literature, where the bulk of scholarship remains focused on the experiences of women. This is due in part to the multiple marginalities MSWs experience and a lack of solid theoretical frameworks. Men are involved in intimate sexual labor within an increasingly global or transnational context, even though intimacy is far more often attributed to the physical and emotional labor of women (Constable, 2009). With prostitution often discursively constituted as “women’s work,” the lack of attention to the risks MSWs face reinforces the very dualism that many feminists would wish to challenge, since it reproduces preexisting heteronormative assumptions about gender in which women are “naturally” sexual objects. Thus, work on MSWs strongly challenges prevailing gender logic (Smith, 2011). Similarly, in contrast to research on women, research on male sex workers often focuses on sexual orientation; by contrast, female sex workers are rarely asked in studies if they enjoy heterosexual activity. This points to a need for more nuanced discussions on scholarly preconceptions about male and female bodies and the possibilities of same-sex desire.

Another reason for the lack of attention given to men and boys may be the belief that they constitute a negligible proportion of sex workers; “many authors reason that most clients are men, straight men outnumber gay men, and surely only gay men patronize male sex workers” (Dennis, 2008, p. 13). Thus, heteronormative definitions of “male” dominate the literature, especially as it pertains to those who purchase sex, and that when males purchase sex from other males, it cannot be linked to oppression. MSWs often are presented as “active, agentive, capitalizing on their talents, running their own business, never coerced, never degraded” (p. 19). While this may be the case for some high-salaried sex workers, most enter the field because of a lack of other options; many also report having experienced abusive childhoods, no opportunity to acquire legitimate marketable skills, and life on the streets.

Male sex workers are a heterogeneous group with diverse experiences, motivations, and identities. A clear distinction can be made between professional and nonprofessional (“street”) sex workers. Professional MSWs (also referred to as escorts or call boys, and who often solicit over the Internet) tend to be more financially secure, independent, and able to be more selective about clients and the types of sexual activities in which they engage. By contrast, nonprofessional sex workers—the focus of this chapter—largely enter this work because of poverty or poor social circumstances. Their environment is characterized by informality, dependency, and financial insecurity. Venue has a clear effect on power and control in sex work interactions, and thus has a direct impact on health and risk behavior (Parsons, 2005; Wright, 2003). While used throughout the literature, “street based” can be a misleading term, since solicitation typically occurs in bars, clubs, casinos, train stations, parks, and inside or in front of sex cinemas. In Germany, migrants dominate these sites because of their structural position as nonprofessional sex workers in addition to language barriers and a resultant inability to find and negotiate with clients over the Internet (although this is changing). Unlike professionalized escort services, street-based sex work is usually a temporary strategy characterized by a shifting set of people and locations. The dynamic features that make these men vulnerable also create significant barriers to social work and public health efforts, including a lack of monitoring data (Wright, 2012).

Migrants selling sex have been long neglected, even within migration studies, resulting in an entire category of labor migration that has been “discursively shunted—or perhaps tidied away” (Agustin, 2006, p. 29). Studies on male, transsexual, and transgender migrants who sell sex are even further marginalized, in part because of the emphasis on trafficking, which is largely viewed as happening only to women. As noted above, male sex workers generally do not fit the portrait of victimization and thus are not targeted by nor eligible for most programs.

Male Sex Workers in Germany

Male sex work has long been an integral part of the sexual topography in Germany. Using police surveillance records, court documents, and social service reports, Evans (2003) explores transgressive sexuality in postwar Berlin, describing men and youths risking incarceration under Germany’s slow-to-be-reformed, Nazi-era anti-sodomy legislation. The

Bahnhof

(train station) in particular became the primary site and symbol of male sex workers in Germany. Especially in Berlin, long divided administratively and sandwiched between two countries, the Bahnhof was thus a potent symbol of political transgression, debates over policing, social welfare, and criminality, as well as the site of much of the city’s clandestine sex trade (Evans, 2003). Red-light districts in Hamburg and public sites in cities like Bonn and Frankfurt have provided spaces for male prostitution since the 1950s (Whisnant, 2006). “Bahnhof boys” were a paradox for social service professionals in the postwar years, as they were viewed as both victims of and contributors to community instability. Hustlers attracted attention in the first half of the 1950s because they combined and concentrated many concerns that were central to public debates in the early Federal Republic: crime, prostitution, homosexuality, youth, and the dangers of the public sphere (Evans, 2003). A number of studies published on male prostitution in this period suggest a pattern of involvement of men between age 16 and 23 of working-class origin, who came from difficult family situations, a lack of economic opportunities, and involvement with other criminal activities (Whisnant, 2006).

Bahnhof

(train station) in particular became the primary site and symbol of male sex workers in Germany. Especially in Berlin, long divided administratively and sandwiched between two countries, the Bahnhof was thus a potent symbol of political transgression, debates over policing, social welfare, and criminality, as well as the site of much of the city’s clandestine sex trade (Evans, 2003). Red-light districts in Hamburg and public sites in cities like Bonn and Frankfurt have provided spaces for male prostitution since the 1950s (Whisnant, 2006). “Bahnhof boys” were a paradox for social service professionals in the postwar years, as they were viewed as both victims of and contributors to community instability. Hustlers attracted attention in the first half of the 1950s because they combined and concentrated many concerns that were central to public debates in the early Federal Republic: crime, prostitution, homosexuality, youth, and the dangers of the public sphere (Evans, 2003). A number of studies published on male prostitution in this period suggest a pattern of involvement of men between age 16 and 23 of working-class origin, who came from difficult family situations, a lack of economic opportunities, and involvement with other criminal activities (Whisnant, 2006).

Other books

The Clan by D. Rus

Move to Strike by Perri O'Shaughnessy

Ever Onward by Wayne Mee

Red Velvet (Silk Stocking Inn #1) by Tess Oliver, Anna Hart

The Highwayman's Lady by Ashe Barker

Stealing Carmen by Faulkner, Gail

Special Ops Affair by Morey, Jennifer

An Alpha's Lightning (Water Bear Shifters 2) by Sloane Meyers

Sanctuary (New Reality Series, Book One) by Jessica Jarman

Romancing the Running Back by Jeanette Murray