Male Sex Work and Society (67 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Drug Use

Research indicates that drug use among Latin America MSWs is high, particularly for those working on the streets (see Grandi et al., 2000; Infante et al., 2009; Mariño et al., 2003; Schifter, 1998, 1999). In the Argentine sample, 51.5 used tobacco daily, 52.2 percent consumed alcohol one to several times a week, 22 percent used marijuana from once a week to every day, and 18.7 percent used cocaine from once a week to every day. Although tobacco and alcohol were used by the majority of the sample, the use of illegal substances like marijuana and cocaine was much lower than their use among MSWs in, for example, Sao Paulo (Grandi et al., 2000). Again, this trend within the Argentine sample may be the result of less precarious work conditions (i.e., working on the street or for pimps), higher levels of education, and being within and providing services to a higher socioeconomic element of the population. Considering that drug use has been associated with STI transmission (Pando et al., 2003), the sexual health characteristics of this group are also of interest.

Sexual Health

In terms of their sexual health, MSWs were “worried” to “very worried” about contracting HIV (81.5 percent) or another STI (82.8 percent) while providing commercial sex services. This concern may be why the vast majority of MSWs indicated that they engage in safer sex practices (e.g., condom use) when providing sexual services. Although they claimed to practice safe commercial sex, these MSWs may still be at risk for STIs and HIV/AIDS, as many had several sexual partners (see Padilla & Castellanos, 2008). For instance, although many of these MSWs (58.1 percent) had a steady partner, 22.5 percent said they had slept with 2-5 other people (not including clients) in the previous 30 days, 26.8 percent had 6-10 other sexual partners, 19 percent had 11-50, and 3.5 percent had had 51-100 other casual partners in the previous year. As indicated earlier, this trend may stem from the macho stereotype within Latin American culture that encourages men to have sex with numerous partners as proof of their prowess (i.e., Cardoso, 2002; Padilla, 2008). As such, MSWs who are concerned about the risk of STIs and HIV/AIDS also live within a sociocultural landscape that may encourage men to have multiple sexual partners. However, the influence of these contradictory messages on the sexual health of MSWs and that of their casual sexual partners is not fully understood.

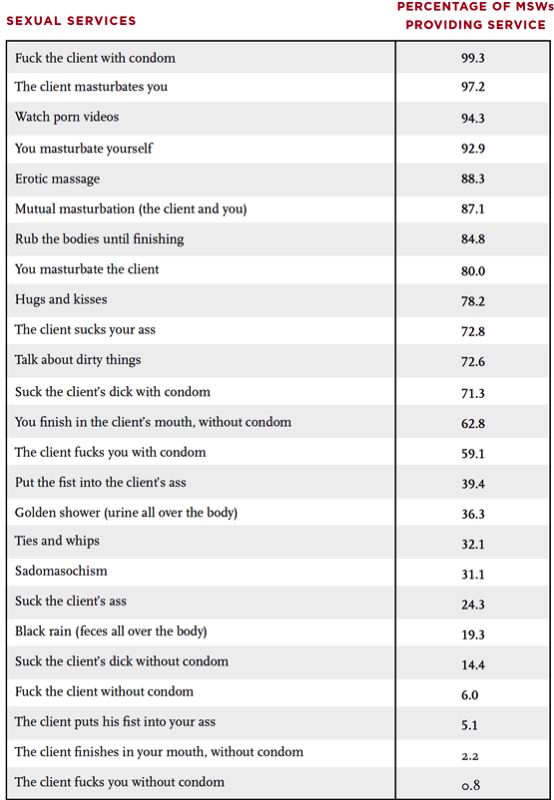

TABLE 15.2

Services MSWs Say They Would Offer Clients

Source:

MAHONY69, 2011

MAHONY69, 2011

Attitudes toward Health-Care Services

Among MSWs who said they had sexual health concerns, 33.3 percent indicated that they avoided public (26.8 percent) health-care services and private (31.7 percent) health-care services. Reasons for this included being worried that health-care staff would ask them if they were sex workers, that they would be asked for their names (4.9-14.6 percent), and the potential link between clinics and police (7.3 percent). The avoidance of both public and private health-care services may speak to the social stigma associated with sex work (see Allen, 2007; Padilla & Castellanos, 2008) and men who transgress the Latin America macho stereotypes (Campuzano, 2009; Padilla, 2008; Schifter, 1998, 1999). For instance, if MSWs are asked if they engage in sex work, they may subsequently be asked about the services they provide. This may mean disclosing that they perform insertive anal sex being the top (99.3 percent of the sample did this with a condom; see

table 15.2

), and perform receptive anal sex being the bottom (59.1 percent did with a condom). Independently, either of these activities may not be more stigmatizing than being homosexual. However, as mentioned above, men who are both tops and bottoms in their sexual encounters (with men or women) may not be perceived as truly macho men because their sexual behavior and/or preferences encompass both sides of the gender divide (see Parker, 1999; Phua, 2010; Schifter, 1998, 1999).

table 15.2

), and perform receptive anal sex being the bottom (59.1 percent did with a condom). Independently, either of these activities may not be more stigmatizing than being homosexual. However, as mentioned above, men who are both tops and bottoms in their sexual encounters (with men or women) may not be perceived as truly macho men because their sexual behavior and/or preferences encompass both sides of the gender divide (see Parker, 1999; Phua, 2010; Schifter, 1998, 1999).

Although 78 percent of the MSW respondents thought the healthcare services available were “good” to “excellent” in dealing with their STI concerns, many also perceived that the services were inaccessible. Reasons for inaccessibility included long wait times to see a doctor (67.2 percent), inconvenient clinic hours (29.9 percent), being treated badly by clinic staff (15.7 percent), distance to the clinic (8.2 percent), and the cost of services (6.7 percent). Even though some MSWs avoided health-care services or felt they were inaccessible, 70.9 percent indicated that if they needed medical advice for an STI they would go to the public hospital; 21.1 percent said they would go to a private clinic, 18.3 percent would consult a friend or relative, and 4.2 percent would seek advice from other MSWs.

Considering these findings, Argentine MSWs may have higher than average knowledge of the potential gravity of STIs and HIV/AIDS and would seek medical advice, even when health-care services create and/or perpetuate the stigma against sex work and MSWs, in addition to lack of access to health services. Two additional characteristics of this sample may also play a role in their potentially higher than average sexual health knowledge and awareness:

Education level.

According to research across numerous disciplines and global populations (Anwar, Sulaiman, Anmadi, & Khan, 2010; Cooper, 2011; Juelson, 2008; Mudingayi, Lutala, & Mupenda, 2011), higher levels of education are associated with higher than average sexual health knowledge and awareness. Because the Argentine MSW respondents were generally more educated than MSWs in some other Latin America studies (see Cortez et al., 2011; Grandi et al., 2000; Infante et al., 2009; Padilla & Castellanos, 2008), they may also have more sexual health knowledge and awareness.The legality of sex work in Argentina.

In countries where sex work is legal or decriminalized, sex workers have better access to sexual health knowledge and awareness than those in countries where sex work is illegal (Aggleton et al., 2003; Arnold & Barling, 2003; Vandepitte et al., 2006). This may be due to a higher incidence of sex worker associations and unions, which advocate safe sexual activities with clients and partners, provide social support, and promote sex worker education and rights. As such, the Argentine sample may generally engage in safer sex practices and seek out medical advice about their sexual health concerns because they have access to support systems and may be educated about their labor and social rights (see also Disogra, Mariño, & Minichiello, 2005; Mariño et al., 2000).

MSWs and the Law

A testament to the legality of sex work in Argentina is the fact that 65 percent of the MSWs indicated that they had never had contact with police while working. This also may be due to the fact that the vast majority of the MSWs in this sample worked privately and only advertised their services in gay newspapers, on websites, or in chat rooms dedicated to the sex industry. Of the 35 percent who had encountered police when working, 46.3 percent said such an event was rare, 37.3 percent said these events occurred “from time to time,” and 11.5 percent said they experienced these encounters almost the entire time they had worked.

Reported by 35 percent of the sample, the type of police encounters were varied and included being told to vacate the street (14), being treated well (13), being asked for money (8), being asked for services for which the police officer paid (6), being arrested (6), being mocked (4), being sexually abused (2), being physically abused (2), and not being paid for services (1). Although some MSWs had negative and/or abusive encounters with police, the low incidence may again speak to the legal status of sex work in Argentina and the availability of peer support and sex worker rights (see Disogra et al., 2005).

Conclusion

This chapter has illustrated how the unique circumstances of defining masculinity in a Latin American cultural and social context shape how male sex work in Latin America unfolds. There are some important differences in how the male sex industry is structured and how the interaction between clients and sex workers evolves and changes within these cultural contexts. Unlike the sex industry in North America and Europe, there appears to be greater fluidity in the expression of sexuality in Latin America. For example, the majority of the escorts advertising on the Internet advertised their services to both men and women; this contrasts with findings on North American websites, where the focus is on male-to-male sex (see

chapters 4

and

5

). This of course also creates a different context for the spread of STIs and may explain why the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in South America shows a more equal proportion of men and women in high-risk groups.

chapters 4

and

5

). This of course also creates a different context for the spread of STIs and may explain why the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in South America shows a more equal proportion of men and women in high-risk groups.

Another difference worth noting is that, with the higher levels of poverty and unemployment in such countries, more young males, including straight identifying males, are turning “gay for pay” and offering top services to clients. That there is a growing market for male sexual services, openly expressed via websites and chat rooms and increasingly in the local press, indicates that the sexual landscape is changing in these countries. The focus is less on explaining why this phenomenon is occurring and more on how to adapt the business to effectively meet the needs of clients and people who seek to work in the male sex industry. Gay issues are also receiving increased political attention. For example, the governments in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay have passed legislation recognizing gay marriage, and with such rights comes a more open debate about sexual and intimate relations between men. This puts more focus on the multiple sexualities found in those (and all) cultures and creates more positive opportunities for younger men to sexualize their bodies, including selling them for money. The oldest profession clearly is becoming less gender specific.

Sex worker education, empowerment, and services are limited or sparse in Latin America. Notably, STI and HIV/AIDS prevention and interventions that encourage MSWs and their clients to use condoms during commercial sex encounters and with their steady and casual partners is needed. Such programs must take into account the many differences throughout Latin America’s sex work populations. For example, many “tops” do not identify as gay and also have sex with women. This creates a different set of sexual health contexts and discourses about how to approach public health—should a campaign be directed to gay forums or to forums where women are the clients and female partners of MSWs. Should the message be different for each context? The availability of the Internet to male commercial sex operations can also be seen as an opportunity to reach more people with targeted interventions. From a technical standpoint, there already are several explanatory models of safer sex to inform those interventions. What is needed now is the political will to fund and carry them out in the countries where they are needed most.

Finally, it is evident from the images included in this chapter that the male body is a sexualized commodity at two levels: as an erotic sexual masculine expression with its own language, visuals, culture, and evolving discourses; and as a way for men to earn money or to purchase male sexual services, with increased visibility and normalized discourses around masculinity and sexuality. Thus, the business of selling sex among men is evolving toward greater societal openness, acceptance, and inclusivity.

References

Aggleton, P., Parker, R. G., & Maluwa, M. (2003).

Stigma, discrimination and HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean

. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank, Sustainable Development Department.

Stigma, discrimination and HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean

. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank, Sustainable Development Department.

Alea, T. G., & Tabío, J. C. (Directors). (1993).

Strawberry and chocolate

[Motion picture]. Mexico.

Strawberry and chocolate

[Motion picture]. Mexico.

Allen, J. S. (2007). Means of desire’s production: Male sex labor in Cuba.

Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power

,

14

, 183-202.

Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power

,

14

, 183-202.

Anwar, M., Sulaiman, S. A. S., Ahmadi, K., & Khan, T. M. (2010). Awareness of school students on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and their sexual behaviour: A cross-sectional study conducted in Palau Pinang, Malaysia.

BMC Public Health, 10

, 1-6.

BMC Public Health, 10

, 1-6.

Arnold, K. A., & Barling, J. (2003). Prostitution: An illustration of occupational stress in “dirty” work. In M. Dollard, H. R. Winefield, & A. H. Winefield (Eds.),

Occupational stress in the service professions

(pp. 261-280). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Occupational stress in the service professions

(pp. 261-280). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Other books

Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes - and Why by Amanda Ripley

Heritage: Book Three of the Grimoire Saga by Boyce, S. M.

Dead Wood by Amore, Dani

The Best of Joe Haldeman by Joe W. Haldeman, Jonathan Strahan

White-Hot Christmas by Serenity Woods

Whirligig by Magnus Macintyre

Glory (Book 1) by McManamon, Michael

The Billionaire's Romance (A Winters Love Book 2) by Rayner, Holly

Bone Orchard by Doug Johnson, Lizz-Ayn Shaarawi

Her Father, My Master: Mentor by Mallorie Griffin