Male Sex Work and Society (32 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

The relationship between an MSW and his client is typically represented as dysfunctional. Ginsburg (1967) and Caukins and Coombs (1976) referred to this relationship as mutually dependent and often transgressing into antagonism and hostility because of the stigma both parties experience. In this early research, there was little room to suggest that satisfaction or reciprocity was involved. With the advent of the gay liberation movement and a shifting understanding of masculinity, researchers began to present MSWs not as the victims of homosexuals but of heterosexism. Kaye (2004) has reported that during the 1970s an increasing number of gay-identified men purchased sex from other gay-identified men. During the 1980s and 1990s, research began to suggest that, while many clients of MSWs were married or had female partners, the majority identified as gay (Bloor, McKeganey, & Barnard, 1990). A new understanding of the MSW encounter emerging in the research reevaluated MSWs and their clients in a more positive light. Salamon (1989), for example, noted that some negative portrayals of clients were part of a strategy by MSWs to negotiate their own perceived deviant status. During the 1990s, research increasingly highlighted the diversity of MSW clients in terms of background, motivation, sexuality, and experience (Goodley, 1995).

Today, the men engaging the services of MSWs are understood to be a diverse group, as are the clients of FSWs. In fact, some research has found little difference in the demographic or sexual history of the clients of male prostitutes and their nonpurchasing peers, except that some male clients are slightly older and better educated (Pitts et al., 2004). Other research has found that clients of MSWs are usually middle class and from 20 to 60 years old (Minichiello et al., 1999), but their age tends to vary globally. Research in the U.S., for example, suggests that younger men are more likely to engage MSWs (Brewer, Muth, & Potterat, 2008), while research from Australia (Coughlan, Mind, & Estcourt, 2001) and Spain (Belza et al., 2008) reports the opposite. A recent survey of an online MSW client community characterized the average client as white, middle-aged, single, HIV-negative, middle class, and gay-identified (Grov et al., 2013). The survey also reported that around 40 percent of the sample was presently or had previously been in a relationship with a woman, and approximately 25 percent identified as straight or bisexual.

Our understanding of the diversity of this population continues to expand, particularly in light of new avenues for sex work through the Internet and mobile technologies. The Internet enables people previously restricted from sex work geographically or demographically to meet and engage with MSWs (Logan, 2010). Agresti (2007) suggests that clients of Internet-based male escorts tend to be of higher socio-economic status and have a lower incidence of drug use or dependence than clients who meet MSWs on the street or in bars.

The Internet also provides new ways for researchers to explore the characteristics of MSWs’ clients. Through our own review of nearly 800 online client profiles posted on the website Daddy’s M4M Reviews (

www.daddysreviews.com/cruise

) by men in the U.S., including California specifically, the UK, and Australia, a fascinating picture of client demographics emerges.

www.daddysreviews.com/cruise

) by men in the U.S., including California specifically, the UK, and Australia, a fascinating picture of client demographics emerges.

Reviews were sampled over four weeks during July/August 2013 and any recent post was included (i.e., posted no earlier than 2010).

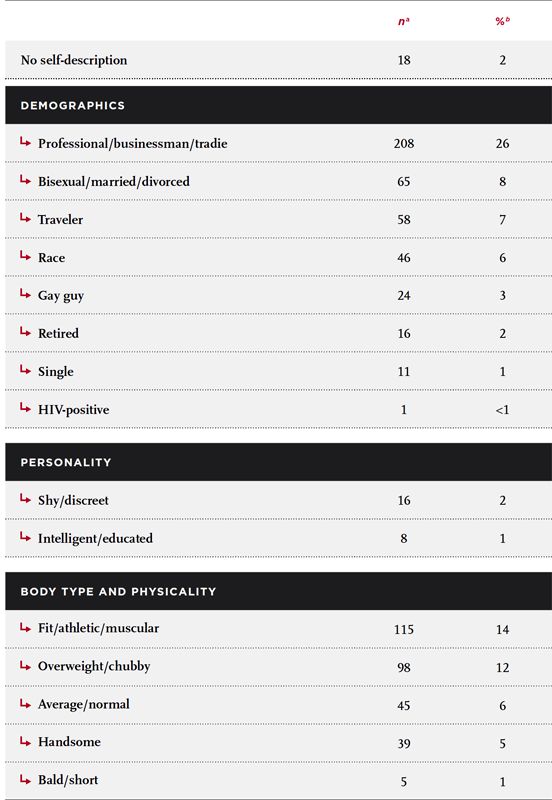

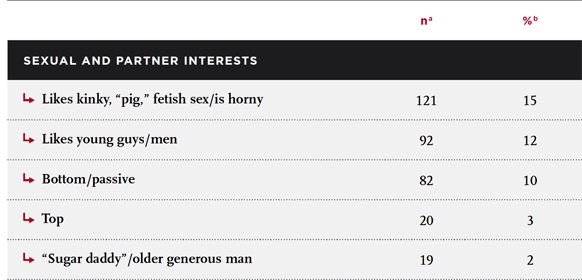

Table 6.1

details the self-descriptions clients posted online; it is notable that only a tiny minority (2 percent) provided no self-description. The remaining profiles contained at least one self-descriptive comment, and most described their authors in multiple ways. We organized the profile descriptions under four thematic headings: demographics, personality body type and physicality, and sexual/partner interests. Demographically, over one-quarter of the profiles sampled referred to their employment using language like “businessman,” “professional,” or “tradie” (slang for tradesperson), and 16 profiles (2 percent) were posted by retired men. Several profiles self-reported their age, ranging collectively from 20 years old to over 70, but most posts came from those in the 40-59 age range (

n

= 413, 51 percent). A few profiles referenced sexuality (

n

= 65, 8 percent), but only one (< 1 percent) discussed HIV status. A small number of profiles also offered descriptions relating to personality, such as “shy” or “discreet” (

n

= 16, 2 percent) and “intelligent” or “educated” (

n

= 8, 1 percent). References to body type and physicality were quite common, with men presenting themselves as “fit,” “athletic,” and/or “muscular” (

n

= 115, 14 percent), overweight or “chubby” (

n

= 98, 12 percent), or with average/normal body type (

n

= 45, 6 percent). Several men also described their sexual interests, such as sexual position.

Table 6.1

details the self-descriptions clients posted online; it is notable that only a tiny minority (2 percent) provided no self-description. The remaining profiles contained at least one self-descriptive comment, and most described their authors in multiple ways. We organized the profile descriptions under four thematic headings: demographics, personality body type and physicality, and sexual/partner interests. Demographically, over one-quarter of the profiles sampled referred to their employment using language like “businessman,” “professional,” or “tradie” (slang for tradesperson), and 16 profiles (2 percent) were posted by retired men. Several profiles self-reported their age, ranging collectively from 20 years old to over 70, but most posts came from those in the 40-59 age range (

n

= 413, 51 percent). A few profiles referenced sexuality (

n

= 65, 8 percent), but only one (< 1 percent) discussed HIV status. A small number of profiles also offered descriptions relating to personality, such as “shy” or “discreet” (

n

= 16, 2 percent) and “intelligent” or “educated” (

n

= 8, 1 percent). References to body type and physicality were quite common, with men presenting themselves as “fit,” “athletic,” and/or “muscular” (

n

= 115, 14 percent), overweight or “chubby” (

n

= 98, 12 percent), or with average/normal body type (

n

= 45, 6 percent). Several men also described their sexual interests, such as sexual position.

The range of research presented here highlights the challenge of generalizing the reported demographic and behavioral factors associated with paying for sex. As noted, it may be that the clients of MSWs and FSWs are not much different from the general population of men (Monto & McRee, 2005; Pitts et al., 2004).

TABLE 6.1

Self-Description in Online Client Profile

a

Some men used multiple descriptions in one profile.

Some men used multiple descriptions in one profile.

b

Proportions were calculated based on total sample size (

N

= 799).

Proportions were calculated based on total sample size (

N

= 799).

Client Motivation

The available research on sex work clients reveals a strong interest in what motivates individuals to purchase sex. Early research in this area suggested that men sought out sex workers to satisfy “perverse” or illegal sexual practices, such as oral sex (Kinsey et al., 1948). Sixty years later, Wilcox and Christmann (2008) undertook a global review of research on client motivation and produced a more diverse list of reasons. Sexual variation, sexual gratification, dissatisfaction with existing relationships, risk-taking, loneliness, psychological and/or physiological incapacity, and a desire to exercise control over the sexual experience were all listed in that review. Sanders (2008) constructed a typology of clients that included a range of motivations, among them exploration, control, and compulsion. Despite the diverse motivations presented in the research, the purchase of sex remains linked to a common perception that clients are incapable of forming “real” sexual or romantic connections (Caldwell, 2011). Drawn from across the available research, motivations can be organized as follows.

Seeking Power

Some research has pointed to the oppressive aspect of sex work as a motivating factor for some clients of FSWs (Vanwesenbeeck, de Graaf, Van Zessen, & Straver, 1993). In one study that compared those who had not paid for sex to the clients of FSWs, the clients tended to have higher rates of criminal activity, lower levels of empathy toward sex workers, and an increased likelihood of committing rape (Farley et al., 2011). Men in that sample also repeatedly expressed enjoyment over the power dynamics of the FSW-client relationship, partly due to the potential to objectify women. Another study reported that, when compared to infrequent or onetime clients, men who regularly hired FSWs tended to more readily accept beliefs that supported or justified sexual violence against women (Monto & Hotaling, 2001). A desire for power among the clients of MSWs may be linked to the negotiation of condom use and anal sex. Although some research has found that only a minority of men request barebacking (i.e., condomless sex) from MSWs (Mariño, Minichiello, & Disogra, 2004; Minichiello et al., 1999), such requests appear to have risen over the past decade (Bimbi & Parsons, 2005; Parsons, Koken, & Bimbi, 2007). Given that bareback sex has been discussed in relation to power dynamics, objectification, and masculinity (Minichiello, Harvey, & Mariño, 2008; Ridge, 2004), clients who request this may be expressing a desire to exert power over a sex worker or, conversely, to have the sex worker exert power over them. The significance of this connection is highlighted by a study that found client violence against MSWs was often linked to disagreements over barebacking (Jamel, 2011).

Seeking Intimacy

A search for intimacy has been found to be a motivating factor behind men’s purchase of sex, with up to one-third of the clients of FSWs seeking an emotional connection (Milrod & Weitzer, 2012). In contrast to clients interested in the oppressive aspects of sex work, Sanders (2008) found that many clients are respectful of sex workers and seek an emotional connection with them. Furthermore, clients posting online often reported that giving pleasure was as important as receiving it, particularly in the context of masculine identities (Earle & Sharp, 2007). This finding is echoed in other research, which notes that some aspects of traditional courtship occur between FSWs and their clients (Earle & Sharp, 2008). An interest in intimacy, sometimes referred to as a girlfriend/boyfriend experience, seems to hold a particular spot in sex work culture and highlights the potential for transactions to include an emotional element (Earle & Sharp, 2008; Weitzer, 2009). A review of Internet-based advertisements for escorts in the U.S. suggests that the offer of a girlfriend experience is more common than offers for specialized sexual practices, such as S&M or anal sex (Pruitt & Krull, 2010), which might reflect a relatively high demand for this service. Research specific to the clients of MSWs also found that intimacy, companionship, and a desire for emotional support are motivating factors for the purchase of sex (Harriman, Johnston, & Kenny, 2007; Minichiello et al., 2000; Smith & Seal, 2008).

Seeking Sensation

Finally, some men may pay for sex to get more sexual variety than they find in their existing sexual relationships (Della Guista, Di Tommaso, Shima, & Strøm, 2009; Xantidis & McCabe, 2000). It also has been suggested that some men engage an FSW to satisfy sexual interests they feel are not being met (Watson & Vidal, 2011), and that men who engage the services of MSWs may also be seeking to fulfill unmet sexual interests (Harriman et al., 2007).

Motivation, Sex, and Self-Identity: A Client Case Study

The research in the previous sections highlights the diversity of clients in terms of their characteristics and their motivations for engaging sex workers. We are currently conducting an interview-based research study of these themes, which aims to collect qualitative data on MSW clients that will allow us to understand more fully how such men give meaning to the potential contradictions paying for sex with a man may create for masculinity. Clients are recruited for the study through a dedicated website (

www.talkaboutmalesexwork.com

), where we collect prescreening information and arrange an anonymous telephone interview. One early finding from this research is that clients do not represent a cohesive or connected community and it is often only the identity of “client” that connects them in any way. Here we consider an interview with a client we call Client X as a case study of the different needs and perspectives associated with “being a man.” This particular client presents many challenges to the notions of masculine sex and a male perspective.

www.talkaboutmalesexwork.com

), where we collect prescreening information and arrange an anonymous telephone interview. One early finding from this research is that clients do not represent a cohesive or connected community and it is often only the identity of “client” that connects them in any way. Here we consider an interview with a client we call Client X as a case study of the different needs and perspectives associated with “being a man.” This particular client presents many challenges to the notions of masculine sex and a male perspective.

Client X has some common demographic characteristics described earlier in this chapter. At the time of the interview, he was in his late forties, a highly successful businessman who traveled far and frequently and enjoyed an affluent lifestyle. He had been married to a woman and had two children. Most striking about the interview with Client X was the importance he placed on sex and sexuality in relation to his self-identity. In response to the question, “How important is sex to you?” he replied without hesitation:

Other books

Space in His Heart by Roxanne St. Claire

Backlash by Lynda La Plante

TREASURE by Laura Bailey

Rich Man's Coffin by K Martin Gardner

Love and Other Unknown Variables by Shannon Alexander

Spartan Gold by Clive Cussler

The Boats of the Glen Carrig by William Hope Hodgson

The Last Summer of the Water Strider by Tim Lott

Tessa Ever After by Brighton Walsh