Male Sex Work and Society (34 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Regulation and Criminalization

As Serughetti (2013) points out, the focus on the most degrading and coercive aspects of sex work, including the construction of clients as violent and dangerous, has played a major part in its stigmatization. In the last part of the 20

th

century, the most negative characterizations of clients shifted interest away from sex workers and toward their (male) clients. This shift fostered not only more research on clients but also a trend in many parts of the world toward criminalizing those who purchase sex. Clients have been blamed for the proliferation of the sex market and thus for the oppression of the workers in that market. This association of blame explains why some countries, among them Sweden, Northern Ireland, Norway, and England, have legalized the selling of sex but made its purchase illegal. In some large U.S. cities, clients have become the target of police crackdowns, and the shifting bounds of criminalization in some parts of the world now include programs aimed at decreasing sex work re-offense, which were originally called “john schools.” The first john school was started in San Francisco in 1995 and has since been renamed the First Offender Prostitution Program. This program has helped to reduce the number of clients arrested for re-offending (Shively et al., 2008), but a study of the program found that while re-offense rates did drop among clients who participated in the program, a similar drop was observed among men who did not attend (Monto & Garcia, 2001). Programs based on the john school model have been introduced in Canada, South Korea, the UK, and elsewhere in the U.S., but as Cook (2013) points out, they are almost exclusively aimed at the male clients of street-based FSWs. Nevertheless, they represent part of the regulatory shift toward the clients of sex workers.

th

century, the most negative characterizations of clients shifted interest away from sex workers and toward their (male) clients. This shift fostered not only more research on clients but also a trend in many parts of the world toward criminalizing those who purchase sex. Clients have been blamed for the proliferation of the sex market and thus for the oppression of the workers in that market. This association of blame explains why some countries, among them Sweden, Northern Ireland, Norway, and England, have legalized the selling of sex but made its purchase illegal. In some large U.S. cities, clients have become the target of police crackdowns, and the shifting bounds of criminalization in some parts of the world now include programs aimed at decreasing sex work re-offense, which were originally called “john schools.” The first john school was started in San Francisco in 1995 and has since been renamed the First Offender Prostitution Program. This program has helped to reduce the number of clients arrested for re-offending (Shively et al., 2008), but a study of the program found that while re-offense rates did drop among clients who participated in the program, a similar drop was observed among men who did not attend (Monto & Garcia, 2001). Programs based on the john school model have been introduced in Canada, South Korea, the UK, and elsewhere in the U.S., but as Cook (2013) points out, they are almost exclusively aimed at the male clients of street-based FSWs. Nevertheless, they represent part of the regulatory shift toward the clients of sex workers.

Normalization and the Internet

Among FSWs and MSWs alike, there appears to be a significant decrease in the number of street sex workers and an increase in those who use the Internet to advertise their services and engage clients (Gaffney, 2003). While the online context does not completely negate the risks associated with sex work, given the strong connection between street sex work and violence, it does show some promise of improving the working conditions for sex workers and the safety of their clients.

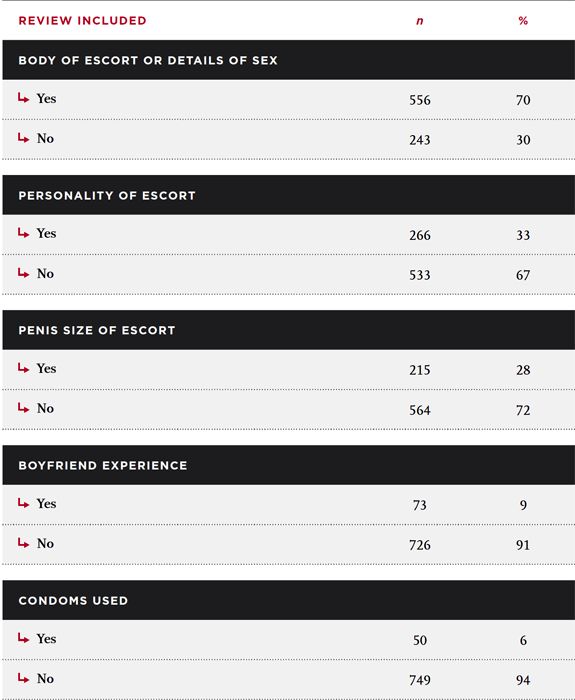

The Internet has brought the previously deviant and largely solitary behavior of clients into a public forum (Holt & Blevins, 2007). Online forums enable clients to discuss hiring sex workers, which, it has been pointed out, may also enable law enforcement to monitor sex work (Holt & Blevins, 2007; Soothill & Saunders, 2005). As noted earlier, MSWs’ online profiles can give clients insight into their characteristics and motivations. It also provides a venue for sex-worker reviews, which are often quite detailed and address a variety of issues, such as safety, performance, and cleanliness (Holt & Blevins, 2007). In

table 6.2

we have compiled some characteristics found in reviews posted online by MSW clients, which are taken from the sample noted earlier in this chapter.

table 6.2

we have compiled some characteristics found in reviews posted online by MSW clients, which are taken from the sample noted earlier in this chapter.

Clients often review sex workers’ physicality and the sexual experience, and, to a lesser extent, personality and penis size. Our review also found that a central aspect of these posts is to describe client satisfaction with the MSW experience. The vast majority posted about positive experiences.

Conclusions, Contrasts, Comparisons

This review describes the ways past research has approached concepts related to the clients of sex workers. Historically, the conceptualization of clients and, to some extent, sex workers has differed greatly between MSWs and FSWs. It is hard to make demographic comparisons between client groups, as the available research generally fails to agree on what makes a “typical” client, other than an increasing recognition of the diverse characteristics of those who purchase sex. Motivations for purchasing sex among the clients of MSWs and FSWs may be similarly diverse but comparable. Thus, while broad descriptive and motivation categories may be useful, attempts to neatly define demographic or behavioral profiles seem to be limited. It does appear that a lot can be gained, however, from engaging directly with clients, which may address gaps not only in our understanding of sex work and clients but also, more broadly, in our notions of masculinity and gender.

TABLE 6.2

Attributes of Escorts and Sex Described by Clients (

N

= 799)

N

= 799)

Historical intolerance of homosexuality has been influential in the construction of MSWs and their clients. Only through a recognition of the earlier legal and pathological paradigms associated with homosexuality can we truly unpack the historical position of MSWs and their clients, which is markedly different from the position of FSWs and their clients. Recent shifts in gendered discourse hints at major changes in the face of male sex work, and future research will be enriched by attempting to capture the new contexts from which clients are emerging. Two broad understandings of sex work clients already have emerged—one that views sex work as an expression of male power and hegemonic masculinity, and another that views it as a product of more diverse and even fragile forms of masculine expression—which does not discount the possibility that such experiences may be socially positive.

References

Agresti, B. T. (2007).

E-prostitution: A content analysis of internet escort websites

. Unpublished thesis, George Washington University, Washington, DC.

E-prostitution: A content analysis of internet escort websites

. Unpublished thesis, George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Barbes, H. (2009, February 27). Women who pay for sex.

BBC Radio 5 Live

. Retrieved from

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7914639.stm

BBC Radio 5 Live

. Retrieved from

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7914639.stm

Belza, M. J., de la Fuente, L., Suárez, M., Vallejo, F., García, M., & López, M. et al. (2008). Men who pay for sex in Spain and condom use: Prevalence and correlates in a representative sample of the general population.

Sexually Transmitted Infections, 84

, 207-211.

Sexually Transmitted Infections, 84

, 207-211.

Benjamin, H., & Masters, R. E. L. (1964).

Prostitution and morality: A definitive report on the prostitute in contemporary society and an analysis of the causes and effects of the suppression of prostitution

. New York: Julian Press.

Prostitution and morality: A definitive report on the prostitute in contemporary society and an analysis of the causes and effects of the suppression of prostitution

. New York: Julian Press.

Bernstein, E. (2005). Desire, demand, and the commerce of sex. In E. Bernstein & L. Schaffner (Eds.),

Regulating sex: The politics of intimacy and identity

(pp. 101-128). New York: Routledge.

Regulating sex: The politics of intimacy and identity

(pp. 101-128). New York: Routledge.

Bimbi, D. S., & Parsons, J. T. (2005). Barebacking among Internet based male sex workers.

Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 9

, 85-105.

Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 9

, 85-105.

Bloor, M., McKeganey, N., & Barnard, M. (1990). An ethnographic study of HIV-related risk practices among Glasgow rent boys and their clients: Report of a pilot study.

AIDS Care, 2

, 17-24.

AIDS Care, 2

, 17-24.

Brewer, D. D., Muth, S. Q., & Potterat, J. J. (2008). Demographic, biometric, and geographical comparison of clients of prostitutes and men in the US general population.

Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 11

. Retrieved from

http://mail.ejhs.org/volume11/brewer.htm

Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 11

. Retrieved from

http://mail.ejhs.org/volume11/brewer.htm

Brooks-Gordon, B. (2006).

The price of sex

. New York: Taylor & Francis.

The price of sex

. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Caldwell, H. (2011)

Long-term clients who access commercial sexual services in Australia

. Master’s thesis, University of Sydney.

Long-term clients who access commercial sexual services in Australia

. Master’s thesis, University of Sydney.

Carael, M., Slaymaker, E., Lyerla, R., & Sarkar, S. (2006). Clients of sex workers in different regions of the world: Hard to count.

Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82

, iii26-iii33.

Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82

, iii26-iii33.

Carballo-Diéguez, A., Ventuneac, A., Dowsett, G. W., Balan, I., Bauermeister, J., Remien, R. H. et al. (2011). Sexual pleasure and intimacy among men who engage in “bareback sex.”

AIDS Behavior, 15

, S57-S65.

AIDS Behavior, 15

, S57-S65.

Caukins, S. E., & Coombs, N. R. (1976). The psychodynamics of male prostitution.

American Journal of Psychotherapy, 30

, 441-451.

American Journal of Psychotherapy, 30

, 441-451.

Chang, J., Thompson, J., & Harold, K. (2012, February 16). Secrets of gigolos: Why more women say they are willing to pay for sex.

ABC News

. Retrieved from

http://abcnews.go.com/Business/secrets-gigolos-women-pay-sex/story?id=15644065#.UawA_tJmjTo

ABC News

. Retrieved from

http://abcnews.go.com/Business/secrets-gigolos-women-pay-sex/story?id=15644065#.UawA_tJmjTo

Cook, I. (2013).

Sex, education and the city: The urban politics and pedagogies of kerb-crawling education programmes

(Imagining Urban Futures working paper 11). Retrieved from

http://research.northumbria.ac.uk/urbanfutures/

Sex, education and the city: The urban politics and pedagogies of kerb-crawling education programmes

(Imagining Urban Futures working paper 11). Retrieved from

http://research.northumbria.ac.uk/urbanfutures/

Coughlan, E., Mindel, A., & Estcourt, C. S. (2001). Male clients of female commercial sex workers: HIV, STDs and risk behaviour.

International Journal of STD & AIDS, 12

, 665-669.

International Journal of STD & AIDS, 12

, 665-669.

Decker, M. R., Raj, A., Gupta, J., & Silverman, J. G. (2008). Sex purchasing and associations with HIV/STI among a clinic-based sample of U.S. men.

Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 48

, 355-360.

Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 48

, 355-360.

Della Giusta, M., Di Tommaso, M. L., Shima, I., & Strøm, S. (2009). What money buys: Clients of street sex workers in the U.S.

Applied Economics, 41

, 2261-2277.

Applied Economics, 41

, 2261-2277.

Earle, S., & Sharp, K. (2007). Sex in cyberspace: Men who pay for sex. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

Earle, S., & Sharp, K. (2008). Intimacy, pleasure and the men who pay for sex. In G. Letherby, K. Williams, P. Birch, & M. Cain (Eds.),

Sex as crime?

London: Willan.

Sex as crime?

London: Willan.

Edlund, L., & Korn, E. (2002). A theory of prostitution.

Journal of Political Economy, 110

, 181-214.

Journal of Political Economy, 110

, 181-214.

Elifson, K. W., Boles, J., Darrow, W. W., & Sterk, C. E. (1999). HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among clients of female and male prostitutes.

Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 20

, 195-200.

Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 20

, 195-200.

Estcourt, C. S., Marks, C., Rohrsheim, R., Johnson, A. M., Donovan, B., & Mindel, A. (2000). HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and risk behaviours in male commercial sex workers in Sydney.

Sexually Transmitted Infections, 76

, 294-298.

Sexually Transmitted Infections, 76

, 294-298.

Farley, M., Schuckman, E., Golding, J. M., Houser, K., Jarrett, L., Qualliotine, P. et al. (2011).

Comparing sex buyers with men who don’t buy sex: “You can have a good time with the servitude” vs. “you’re supporting a system of degradation.”

Paper presented at the annual meeting of Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Boston, MA.

Comparing sex buyers with men who don’t buy sex: “You can have a good time with the servitude” vs. “you’re supporting a system of degradation.”

Paper presented at the annual meeting of Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Boston, MA.

Gaffney, J. (2003).

Working together with male sex workers in London

. Paper presented at the European Network of Male Prostitution, Hamburg, Germany.

Working together with male sex workers in London

. Paper presented at the European Network of Male Prostitution, Hamburg, Germany.

Gaffney, J. (2007). Prostitution policy: A co-ordinated prostitution strategy and response to paying the price—but what about the men?

Community Safety Journal, 6

, 27-33.

Community Safety Journal, 6

, 27-33.

Ginsburg, K. N. (1967). The meat-rack: A study of the male homosexual prostitute.

American Journal of Psychotherapy, 21

, 170-185.

American Journal of Psychotherapy, 21

, 170-185.

Goodley, S. (1995). A male sex worker’s view. In R. Perkins et al. (Eds.),

Sex work, sex workers in Australia

(pp. 126-132). Sydney: University of New South Wales.

Sex work, sex workers in Australia

(pp. 126-132). Sydney: University of New South Wales.

Grov, C., Wolff, M., Smith, M. D., Koken, J., & Parsons, J. T. (2013). Male clients of male escorts: Satisfaction, sexual behavior, and demographic characteristics.

Journal of Sex Research

, 1-11.

Journal of Sex Research

, 1-11.

Harriman, R. L., Johnston, B., & Kenny, P. M. (2007). Musings on male sex work: A “virtual” discussion.

Journal of Homosexuality, 53

, 277-318.

Journal of Homosexuality, 53

, 277-318.

Holt, T. J., & Blevins, K. R. (2007). Examining sex work from the client’s perspective: Assessing Johns using on-line data.

Deviant Behavior, 28

, 333-354.

Deviant Behavior, 28

, 333-354.

Hubbard, P. (1999).

Sex and the city: Geographies of prostitution in the urban west

. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

Sex and the city: Geographies of prostitution in the urban west

. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

Hull, P., Mao, L., Kao, S.-C., Edwards, B., Prestage, G., Zablotska, I. et al. (2012).

Gay community period survey: Sydney 2012

. Sydney: University of New South Wales.

Gay community period survey: Sydney 2012

. Sydney: University of New South Wales.

Other books

Diary of a Discontent by Alexander Lurikov

Stealing the Mystic Lamb by Noah Charney

Conspiracy by Allan Topol

Falling to Earth by Kate Southwood

The Invincibles by McNichols, Michael

My Sister Is a Werewolf by Kathy Love

Shadow's Light by Nicola Claire

The Doctor's Daughter by Hilma Wolitzer

The Seducer by Madeline Hunter

Don't Cry for Me by Sharon Sala