Male Sex Work and Society (77 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

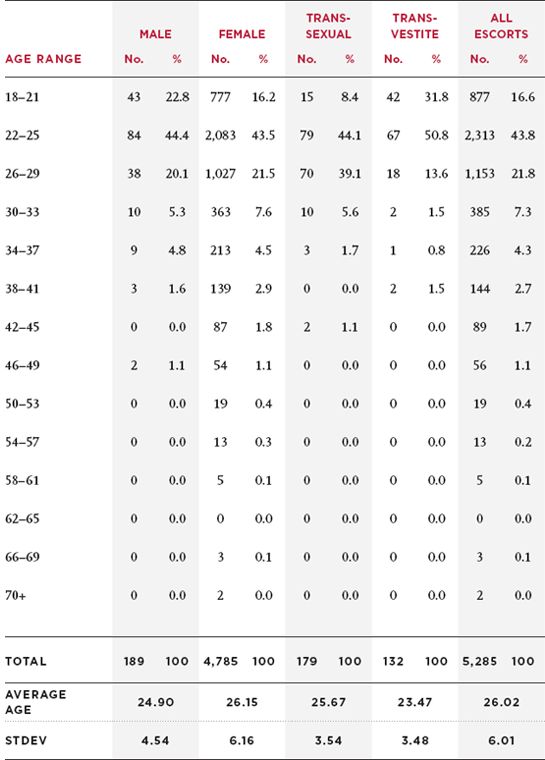

TABLE 17.2

Age Profile of Escorts, 2012

Source

:

www.Escort-Ireland.com

:

www.Escort-Ireland.com

So, what does the age profile of MSWs in Ireland look like and how does it compare with sex workers in other locations? As seen in

table 17.2

, the mean age of all sex workers is 26 (STDEV = 6.01); the mean age of male sex workers is just under 25 (STDEV = 4.54), slightly lower than females at 26.15 (STDEV = 6.16) and transsexuals at 25.67 (STDEV = 3.54), but higher than transvestites at 23.47 (STDEV = 3.48). A significant proportion of MSWs (22.8 percent) was listed as between ages 18 and 21—which is in line with Pruitt’s and Minichiello et al.’s observations—as compared to female (16.2 percent) and transsexual (8.4 percent) sex workers; almost one-third of transvestite escorts, however, were between ages 18 and 21—almost twice the rate for all escorts. The proportion of male sex workers age 18-21 resonates with findings by Logan (2010) and Minichiello et al. (2002) that only a small number of male (n = 2), transsexual (n = 1), and transvestite (n = 1) sex workers were 18 years old. Significantly more female sex workers were listed as being 18 (n = 32), but this age group accounted for just 0.7 percent of total female sex workers. The majority (67.5 percent) of Irish-based MSWs, like their U.S. and Australian counterparts, was found to be between 22 and 30 years old.

table 17.2

, the mean age of all sex workers is 26 (STDEV = 6.01); the mean age of male sex workers is just under 25 (STDEV = 4.54), slightly lower than females at 26.15 (STDEV = 6.16) and transsexuals at 25.67 (STDEV = 3.54), but higher than transvestites at 23.47 (STDEV = 3.48). A significant proportion of MSWs (22.8 percent) was listed as between ages 18 and 21—which is in line with Pruitt’s and Minichiello et al.’s observations—as compared to female (16.2 percent) and transsexual (8.4 percent) sex workers; almost one-third of transvestite escorts, however, were between ages 18 and 21—almost twice the rate for all escorts. The proportion of male sex workers age 18-21 resonates with findings by Logan (2010) and Minichiello et al. (2002) that only a small number of male (n = 2), transsexual (n = 1), and transvestite (n = 1) sex workers were 18 years old. Significantly more female sex workers were listed as being 18 (n = 32), but this age group accounted for just 0.7 percent of total female sex workers. The majority (67.5 percent) of Irish-based MSWs, like their U.S. and Australian counterparts, was found to be between 22 and 30 years old.

In terms of older sex workers, 47 was the maximum age of male sex workers, 44 and 40 for transsexual and transvestite escorts, respectively. There were considerably more older female sex workers, with 269 (5.6 percent) age 40 and above. In fact, the maximum age of female sex workers was 71. This difference in the age range of female and male sex workers raises interesting questions about the market preferences of largely male clients. On face value, it would seem that punters are relatively more discriminatory toward older male than female sex workers, and that career prospects in the sex industry appear to be more durable for women than men.

Nationality of Irish Male Sex Workers

As noted earlier, the Irish economy experienced significant economic growth between 1993 and 2007; that ended with the 2008 global financial crisis. Those years of growth saw many Irish citizens return home after living overseas and fueled considerable immigration of European migrants, including those from countries that became part of the EU in 2004—Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia—and later from Romania and Bulgaria, which became EU members in 2007 (Kitchin, O’Callaghan, Boyle, Gleeson, & Keaveney, 2012; Krings, Bobek, Moriarty, Salamonska, & Wickham, 2009). However, some EU member states, including the UK and Ireland, imposed restrictions on the right of permanent residence and the employment of Bulgarian and Romanian nationals within their respective jurisdictions; Ireland only lifted those restrictions in January 2012 (Citizens Information Board, 2013; Kitchin et al., 2012; Krings et al., 2009). We highlight this broad process of migration because various antisex work advocacy groups in Ireland (e.g., Ruhama and TORL) claim that the fact that the majority of women in sex work in Ireland are not Irish is evidence of widespread human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation. But, as Agustin (2007) has highlighted, it is vitally important to recognize the difference between migrant sex workers and those coerced into sexual servitude, and the great difficulty in being able to ascertain definitively how many people are involved in sex work, whether by choice or as a result of trafficking. This is due to the stigma that surrounds sex work and the increased mobility of sex workers within and across borders. We acknowledge that there may well be some people, particularly women, who have been coerced into sex work in Ireland; however, assertions by some political actors, advocacy groups, and radical feminists that all or the vast majority of female sex workers have been coerced lacks any rigorous empirical basis.

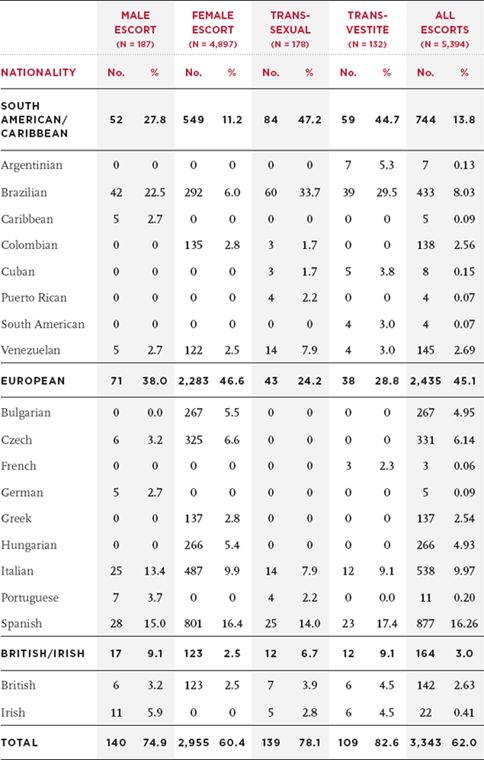

Data from

Escort-Ireland.com

reveal that MSWs identified with 39 different nationalities. Similar numbers were evident for transsexual and transvestite sex workers (38 and 29, respectively), while female sex workers identified with a staggering 123 nationalities. Very few MSWs identified as Irish, a mere 11 (5.9 percent) out of 187. Even fewer transvestite (2.8 percent) and transsexual (4.5 percent) sex workers identified as Irish. Most intriguingly, no female escorts identified as Irish. This was also true of those in NI who identified as British or Irish. British/Irish male escorts accounted for just under 10 percent of the total male sex worker population in Ireland (n = 187)—see

table 17.3

. It is difficult to discern why so few sex workers who work in Ireland identify as Irish. One possible reason is that this identity marker lacks a certain exotic appeal, hence sex workers may advertise themselves under a different and more appealing nationality in order to attract more clients. However, we feel that this is a rather unlikely scenario, as it would be extremely difficult for a male from Ireland to pass as a Brazilian or Italian in the event of a face-to-face meeting. More probably, because of the risk of being stigmatized, Irish escorts and those of other nationalities adopt different cultural or nationality backgrounds to avoid being recognized by someone from their own community. For reasons we elaborate on below, Irish male sex workers do use the Internet to transact commercial sex, but they do so in different ways than foreign nationals.

Escort-Ireland.com

reveal that MSWs identified with 39 different nationalities. Similar numbers were evident for transsexual and transvestite sex workers (38 and 29, respectively), while female sex workers identified with a staggering 123 nationalities. Very few MSWs identified as Irish, a mere 11 (5.9 percent) out of 187. Even fewer transvestite (2.8 percent) and transsexual (4.5 percent) sex workers identified as Irish. Most intriguingly, no female escorts identified as Irish. This was also true of those in NI who identified as British or Irish. British/Irish male escorts accounted for just under 10 percent of the total male sex worker population in Ireland (n = 187)—see

table 17.3

. It is difficult to discern why so few sex workers who work in Ireland identify as Irish. One possible reason is that this identity marker lacks a certain exotic appeal, hence sex workers may advertise themselves under a different and more appealing nationality in order to attract more clients. However, we feel that this is a rather unlikely scenario, as it would be extremely difficult for a male from Ireland to pass as a Brazilian or Italian in the event of a face-to-face meeting. More probably, because of the risk of being stigmatized, Irish escorts and those of other nationalities adopt different cultural or nationality backgrounds to avoid being recognized by someone from their own community. For reasons we elaborate on below, Irish male sex workers do use the Internet to transact commercial sex, but they do so in different ways than foreign nationals.

Despite the large number of nationalities across all sex worker types, the “top 10” nationalities accounted for between 60.4 percent (female) and 82.6 percent (transvestite) of escorts; across all four sex worker types, a total of 19 different countries were represented (see

table 17.3

). A significant proportion of transvestite (47.2 percent) and transsexual (44.7 percent) sex workers identified as being from South American/Caribbean backgrounds, Brazilian being the most common nationality among male (22.5 percent), transsexual (33.7 percent), and transvestite (29.5 percent) sex workers. It is difficult to discern exactly why so many present as Brazilian, but it is true that the Brazilian population in the ROI has increased by a staggering 700 percent, from approximately 1,100 in 2002 to 8,700 in 2011 (Central Statistics Office, 2012). Just over a quarter of all Brazilians in Ireland are students, and approximately 20 percent work in relatively low-skill, low-paid employment sectors—wholesale and retailing, hospitality, and manufacturing—and more than 80 percent are between 15 and 34 years old. These various factors, combined with the economic woes Ireland has experienced over the last five years, may partly explain why some Brazilians (and other migrant groups) have turned to sex work as a way to supplement their incomes (Magnanti, 2012). European nationalities accounted for the largest proportion of male (38 percent) and female (46.6 percent) sex workers. There was a fairly even distribution of nationalities among females and males, with a concentration around two—Spanish (15 percent and 16.4 percent) and Italian (13.4 percent and 9.9 percent) for males and females respectively.

table 17.3

). A significant proportion of transvestite (47.2 percent) and transsexual (44.7 percent) sex workers identified as being from South American/Caribbean backgrounds, Brazilian being the most common nationality among male (22.5 percent), transsexual (33.7 percent), and transvestite (29.5 percent) sex workers. It is difficult to discern exactly why so many present as Brazilian, but it is true that the Brazilian population in the ROI has increased by a staggering 700 percent, from approximately 1,100 in 2002 to 8,700 in 2011 (Central Statistics Office, 2012). Just over a quarter of all Brazilians in Ireland are students, and approximately 20 percent work in relatively low-skill, low-paid employment sectors—wholesale and retailing, hospitality, and manufacturing—and more than 80 percent are between 15 and 34 years old. These various factors, combined with the economic woes Ireland has experienced over the last five years, may partly explain why some Brazilians (and other migrant groups) have turned to sex work as a way to supplement their incomes (Magnanti, 2012). European nationalities accounted for the largest proportion of male (38 percent) and female (46.6 percent) sex workers. There was a fairly even distribution of nationalities among females and males, with a concentration around two—Spanish (15 percent and 16.4 percent) and Italian (13.4 percent and 9.9 percent) for males and females respectively.

TABLE 17.3

Nationality of Escorts, 2012

Source

:

www.Escort-Ireland.com

:

www.Escort-Ireland.com

One issue of note relates to the position of migrant sex workers from Romania and Bulgaria, although this appears to relate primarily to female sex workers. Since our data encompass the period from 2009 to 2012, they may underplay the increasing number of Romanian women who are engaged in the sexual commerce sector in Ireland. While there were female Romanian sex workers in our data, they only accounted for 0.3 percent (n = 17) of our overall sample and thus did not make the top-10 list of nationalities. As noted above, the ROI lifted restrictions on the right of Romanian (and Bulgarian) citizens to permanently reside and work in the country only in July 2012, so our data may understate the current numbers of Romanian sex workers in Ireland.

12

Indeed, a recent self-report survey by UglyMugs.ie (an organization that campaigns for sex worker safety) discovered that just over a quarter (25.7 percent) of Ireland-based sex workers who responded to the survey claimed Romanian nationality (UglyMugs.ie, 2013). This would appear to mirror the pattern for migrant sex workers—particularly from Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary—and their participation in the sex trade in other EU jurisdictions, including the Netherlands and Germany (Day & Wards, 2004; Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012; Katona, 2012).

12

Indeed, a recent self-report survey by UglyMugs.ie (an organization that campaigns for sex worker safety) discovered that just over a quarter (25.7 percent) of Ireland-based sex workers who responded to the survey claimed Romanian nationality (UglyMugs.ie, 2013). This would appear to mirror the pattern for migrant sex workers—particularly from Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary—and their participation in the sex trade in other EU jurisdictions, including the Netherlands and Germany (Day & Wards, 2004; Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012; Katona, 2012).

Ultimately, in order to develop more nuanced insights into the nature of the commercial sex industry in Ireland, more primary survey and qualitative-based research will be required. It will need to explore the demographic profile of male (and female) sex workers in Ireland, why and how they entered the sex industry, what market segments they service, and why and how they see a future in sex work. Conducting such research will be no easy feat, especially within the current political climate, where policy is moving toward eliminating sex work via the so-called Swedish model of regulation, which criminalizes the purchase of sex. As we (and others) have articulated, this is likely to drive sex workers deeper into the shadows of the informal sex economy and thus increase rather than reduce risks to their health and general well-being (Agustin, 2007; Maginn & Ellison, 2013).

Conclusions

As in other jurisdictions, the landscape of commercial sex work in Ireland, north and south, has been fundamentally altered by the development of the Internet as the primary mechanism for transacting sexual commerce for both female and male sex workers. We have noted that the dynamics of male sexual commerce in both parts of Ireland is woefully underresearched, but particularly in NI, where no academic studies have been conducted thus far. Even in the ROI, where slightly more research has been conducted (though much of it predates the Internet), no study of which we are aware has been based on a properly randomized sample that limits the generalizability of the data. The overwhelming majority of studies are based on small convenience samples, usually drawn from a subsection of the sex worker population who seek sexual health or other support services. Furthermore, the stigma traditionally associated with homosexuality in Ireland in general across the social, cultural, and political spheres has meant that researching the issue of male commercial sex has been beset by a number of difficulties. At one level, the issue of homosexuality in Ireland is still, as Oscar Wilde famously noted, the love that dare not speak its name, and as such has remained relatively hidden from official policy debates and public discourse. As noted above, the issue of male commercial sex did not feature at all in the DUP’s proposals to criminalize payment for sex in Northern Ireland. This is not due only to the fact that the issue was perceived to be less of a problem than female sex work, as it also reflects the fact that many in the DUP (which attracts a strong Protestant fundamentalist base) simply refuse to believe or acknowledge that there are men who are willing to both sell and purchase sex from other men.

Our analysis of the data from

Escort-Ireland.com

suggests that the phenomenon of male commercial sex is prevalent in Ireland, although comparatively fewer males than females are involved in the industry. One of the curious aspects of the

Escort-Ireland.com

data concerns the relatively small number of male sex workers who identify as “Irish,” or as “British” if from NI. This may suggest that, for reasons of anonymity, indigenous sex workers do not transact business via a website such as

Escort-Ireland.com

, where they have to maintain a permanent profile. Certainly, the majority of male sex worker profiles are of people who claim a nationality other than Irish or British, Brazilian, Spanish, and Italian being the most common. This may point to two things: first, the relative professionalization of the sector, wherein sex workers from Brazil, for example, appear to be highly mobile and may view sex work as their main job; second, male sex workers from the ROI and NI engage in commercial sex rather more sporadically and transiently and advertise their services using alternative means. A cursory analysis of alternative websites, such as Craigslist, Gaydar, Adultwork, Grindr, Gayswap, Planet Romeo, Vivastreet, and Squirt, indicate that, as far as can be ascertained, the overwhelming majority of sellers who advertise sexual services are based locally. However, advertisements and profiles appear and disappear with rather rapid abandon, sometimes staying live for only a few days at a time. Again, this suggests that sex work for some young men is something that they dip in and out of depending on circumstances; it is not a fixed identity.

Escort-Ireland.com

suggests that the phenomenon of male commercial sex is prevalent in Ireland, although comparatively fewer males than females are involved in the industry. One of the curious aspects of the

Escort-Ireland.com

data concerns the relatively small number of male sex workers who identify as “Irish,” or as “British” if from NI. This may suggest that, for reasons of anonymity, indigenous sex workers do not transact business via a website such as

Escort-Ireland.com

, where they have to maintain a permanent profile. Certainly, the majority of male sex worker profiles are of people who claim a nationality other than Irish or British, Brazilian, Spanish, and Italian being the most common. This may point to two things: first, the relative professionalization of the sector, wherein sex workers from Brazil, for example, appear to be highly mobile and may view sex work as their main job; second, male sex workers from the ROI and NI engage in commercial sex rather more sporadically and transiently and advertise their services using alternative means. A cursory analysis of alternative websites, such as Craigslist, Gaydar, Adultwork, Grindr, Gayswap, Planet Romeo, Vivastreet, and Squirt, indicate that, as far as can be ascertained, the overwhelming majority of sellers who advertise sexual services are based locally. However, advertisements and profiles appear and disappear with rather rapid abandon, sometimes staying live for only a few days at a time. Again, this suggests that sex work for some young men is something that they dip in and out of depending on circumstances; it is not a fixed identity.

Other books

The Sheik’s Captured Princess (The Samara Royal Family Series Book 4) by Elizabeth Lennox

Michael Chabon by The Mysteries of Pittsburgh

Chained (Chained Trilogy) by Elise Marion

The Source of All Things by Tracy Ross

3rd Degree by James Patterson, Andrew Gross

The Lords of Arden by Helen Burton

Welcome To Rosie Hopkins' Sweetshop Of Dreams by Jenny Colgan

Hold Me Close by Shannyn Schroeder

The Cowboy and His Baby by Sherryl Woods

To the Ends of the Earth by William Golding