Mark Griffin (19 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

The Clock

: Minnelli directs Garland in MGM’s version of Central Park, 1944. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

: Minnelli directs Garland in MGM’s version of Central Park, 1944. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

10

“If I Had You”

“I PRODUCED

The Clock

to give Judy a kick. She wanted to do a straight picture,” Arthur Freed recalled—though at first, the producer didn’t think allowing his greatest musical star to appear in a nonmusical film was such a smashing idea. The moviegoing public knew and adored Judy Garland as a singing star, and they paid good money to see her musicals, buy her records, and snap up the sheet music of songs from her movies. The bottom line was that there was plenty of profit to be made whenever Judy Garland belted them out.

The Clock

to give Judy a kick. She wanted to do a straight picture,” Arthur Freed recalled—though at first, the producer didn’t think allowing his greatest musical star to appear in a nonmusical film was such a smashing idea. The moviegoing public knew and adored Judy Garland as a singing star, and they paid good money to see her musicals, buy her records, and snap up the sheet music of songs from her movies. The bottom line was that there was plenty of profit to be made whenever Judy Garland belted them out.

After giving her all in one elaborate MGM musical after another, though, Garland longed for the opportunity to appear in a more modestly scaled production that would allow her to display her dramatic talents (which radio listeners had already been treated to, courtesy of broadcasts of

Morning Glory

and a nonmusical version of

A Star Is Born

several years earlier).

Morning Glory

and a nonmusical version of

A Star Is Born

several years earlier).

Paul and Pauline Gallico’s unpublished short story “The Clock” had caught Freed’s eye. It concerned a lonely, wide-eyed corporal from Mapleton, Indiana, on a forty-eight-hour furlough in New York City who meets a secretary one fateful Sunday afternoon. After a courtship that redefines whirlwind, the couple marries before the soldier ships out again. It was charming. It was timely. There were no big production numbers. And in the form of New Yorker Alice Maybery, Judy had found her first dramatic screen role. Robert Nathan and Joseph Schrank (who had scripted

Cabin in the Sky

) were tasked with adapting the Gallicos’ poignant story.

Cabin in the Sky

) were tasked with adapting the Gallicos’ poignant story.

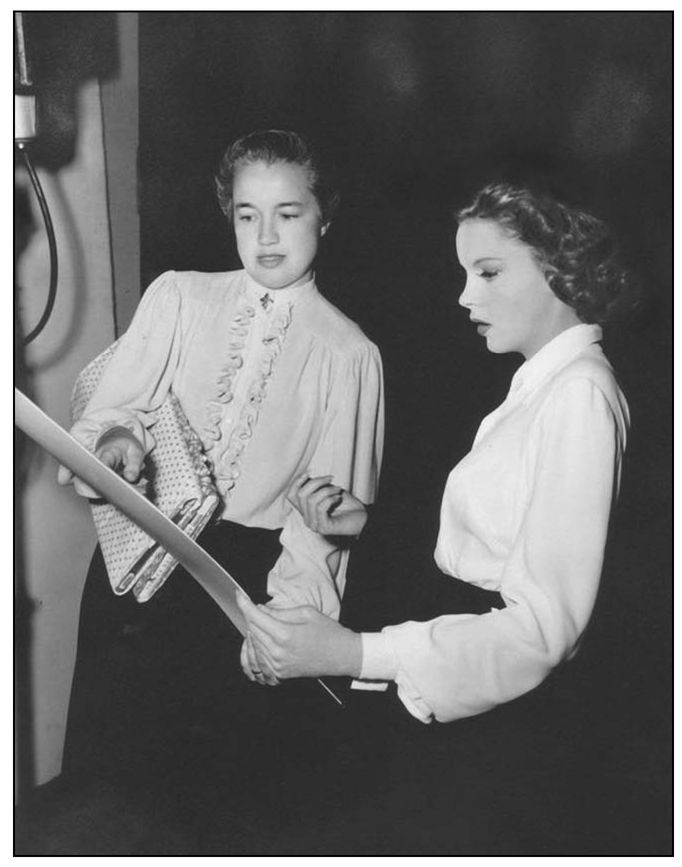

Designing Woman: Minnelli’s former fiancée, costumer Marion Herwood Keyes and his future wife, Judy Garland look over wardrobe designs on the set of

The Clock

. PHOTO COURTESY OF PETER KEYES (PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN)

The Clock

. PHOTO COURTESY OF PETER KEYES (PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN)

Robert Walker, who had already spent plenty of time in uniform, courtesy of MGM’s

See Here

,

Private Hargrove

, and

Thirty Seconds over Tokyo

, would play the lovestruck soldier. Jack Conway, the man who directed Metro’s first talkie (

Alias Jimmy Valentine

in 1928), was originally announced as the director of

The Clock

, but in June 1944, while shooting process shots on location in New York, he fell ill. Production was temporarily halted. When it resumed, Fred Zinnemann was at the helm. Almost immediately, it became apparent that although Zinnemann was a completely capable director, he was not suitably matched with the star.

See Here

,

Private Hargrove

, and

Thirty Seconds over Tokyo

, would play the lovestruck soldier. Jack Conway, the man who directed Metro’s first talkie (

Alias Jimmy Valentine

in 1928), was originally announced as the director of

The Clock

, but in June 1944, while shooting process shots on location in New York, he fell ill. Production was temporarily halted. When it resumed, Fred Zinnemann was at the helm. Almost immediately, it became apparent that although Zinnemann was a completely capable director, he was not suitably matched with the star.

“I don’t know—he must be a good director but I just get nothing. We have no compatibility,” Judy reportedly told Freed.

1

Others close to the production confirm that the lack of chemistry between director and star was an issue from the outset, though some believe that what also concerned Garland was the fact that the rushes revealed that Zinnemann had failed where Minnelli had triumphed. The luminous Judy of

Meet Me in St. Louis

was nowhere to be found in Zinnemann’s footage. Under Minnelli’s indulgent eye, Garland had blossomed as Esther Smith. On Zinnemann’s watch, her Alice Maybery was rather dull and ordinary. “The rushes came in and Judy said it looked like something out of

The Search

,” remembers Garland confidant John Meyer.

2

Zinnemann’s semi-documentary style may have worked for that postwar drama, but it seemed far too somber for an MGM love story. Clearly something would have to be done. Just because Garland was going legit and playing a nonsinging secretary didn’t mean she had to sacrifice every ounce of her newfound glamour. Judy made up her mind: “One day, I went to the officials and told them I knew what the picture needed . . . Vincente Minnelli.”

3

1

Others close to the production confirm that the lack of chemistry between director and star was an issue from the outset, though some believe that what also concerned Garland was the fact that the rushes revealed that Zinnemann had failed where Minnelli had triumphed. The luminous Judy of

Meet Me in St. Louis

was nowhere to be found in Zinnemann’s footage. Under Minnelli’s indulgent eye, Garland had blossomed as Esther Smith. On Zinnemann’s watch, her Alice Maybery was rather dull and ordinary. “The rushes came in and Judy said it looked like something out of

The Search

,” remembers Garland confidant John Meyer.

2

Zinnemann’s semi-documentary style may have worked for that postwar drama, but it seemed far too somber for an MGM love story. Clearly something would have to be done. Just because Garland was going legit and playing a nonsinging secretary didn’t mean she had to sacrifice every ounce of her newfound glamour. Judy made up her mind: “One day, I went to the officials and told them I knew what the picture needed . . . Vincente Minnelli.”

3

While Freed stopped

The Clock

yet again, Garland summoned Minnelli to a lunch meeting at The Player’s Club, the site of countless off-the-lot conferences. Offering Vincente a preview of her dramatic abilities, Judy prevailed upon the same man that she had recently spurned. Her pet project was in jeopardy, and she would do anything to keep it afloat—even if it meant putting personal feelings aside and asking Vincente to take over the picture.

The Clock

yet again, Garland summoned Minnelli to a lunch meeting at The Player’s Club, the site of countless off-the-lot conferences. Offering Vincente a preview of her dramatic abilities, Judy prevailed upon the same man that she had recently spurned. Her pet project was in jeopardy, and she would do anything to keep it afloat—even if it meant putting personal feelings aside and asking Vincente to take over the picture.

Minnelli quickly realized that this was a working lunch and that his meeting with Judy had more than likely been orchestrated by Arthur Freed. Already a studio-savvy diplomat, Vincente agreed to take on the rescue mission, but only if he could talk to Zinnemann first and under the condition that if he did restart

The Clock

, he would be granted complete creative control. Minnelli conferred with Zinnemann, the future director of such four-star classics as

High Noon

and

From Here to Eternity

. The Austrian-born auteur vented about Judy’s unreliability but gave Vincente his blessing to carry on.

The Clock

, he would be granted complete creative control. Minnelli conferred with Zinnemann, the future director of such four-star classics as

High Noon

and

From Here to Eternity

. The Austrian-born auteur vented about Judy’s unreliability but gave Vincente his blessing to carry on.

And, really, who better to direct a New York love story than Metro’s own Greenwich Village refugee? Freed was also shrewd enough to realize that what they were after wasn’t so much New York “realism” but a back-projected facsimile of it—coated with a thick veneer of Metro gloss. Whatever cinema verité flourishes Zinnemann had hoped to introduce went the way of his aborted footage. This would be a wartime romance produced by Arthur Freed and directed by Vincente Minnelli, and any resemblance to actual urban realities was purely coincidental. The producer was hopeful that what Minnelli had done for turn-of-the-century

St. Louis

, he’d be able to do for Culver City’s version of the Big Apple.

St. Louis

, he’d be able to do for Culver City’s version of the Big Apple.

With Garland garnering inordinate attention for appearing in a nonsinging role, nearly everyone overlooked the fact that

The Clock

would be Vincente’s dramatic debut as well. Recognizing this as an opportunity to display his versatility, Minnelli was determined that the picture had to stand out. Before diving in, he looked into whether there was anything worth salvaging from Zinnemann’s efforts.

The Clock

would be Vincente’s dramatic debut as well. Recognizing this as an opportunity to display his versatility, Minnelli was determined that the picture had to stand out. Before diving in, he looked into whether there was anything worth salvaging from Zinnemann’s efforts.

When it was pieced together, Zinnemann’s footage evidenced none of the dramatic effectiveness of his recent Spencer Tracy vehicle

The Seventh Cross

. As Minnelli observed, “Each scene from the two [

sic

] weeks of footage shot thus far looked as if it came from a different picture. It was very confusing. I could see why Metro’s executive committee had canceled the project.”

4

Although a minimal amount of material was retained from Zinnemann’s version, it was clear that Minnelli would have to start from scratch.

The Seventh Cross

. As Minnelli observed, “Each scene from the two [

sic

] weeks of footage shot thus far looked as if it came from a different picture. It was very confusing. I could see why Metro’s executive committee had canceled the project.”

4

Although a minimal amount of material was retained from Zinnemann’s version, it was clear that Minnelli would have to start from scratch.

“We tackled the script,” Vincente recalled. “We kept all the parts we felt were good, and tried to alter the rest. . . . I decided at once to make New York itself another character in the story and I introduced a number of crazy people.” In overhauling the script, Minnelli irked screenwriter Robert Nathan, who complained to Freed, “I still feel very strongly that when a director departs from the instructions in the script, he ought to—if only in politeness—discuss that departure with the writer

before

rather than

after

the scene is shot.” According to Vincente, much of what was removed from Nathan’s script were “sticky spots,” such as a sequence in which Robert Walker befriends a precious young lad in Central Park. “It was all terribly ‘darling,’” Minnelli would later remark. “Instead, I made [the boy] kick Walker and that made him more real, more human.”

5

before

rather than

after

the scene is shot.” According to Vincente, much of what was removed from Nathan’s script were “sticky spots,” such as a sequence in which Robert Walker befriends a precious young lad in Central Park. “It was all terribly ‘darling,’” Minnelli would later remark. “Instead, I made [the boy] kick Walker and that made him more real, more human.”

5

Elsewhere, Minnelli attempted to give the script more atmosphere and local color, and for this he dipped into his own big city experiences: “I tried to remember everything about New York. I set out to create an unexpected gallery of people whose lives might conceivably touch that of the boy and

girl.”

6

For Vincente, New York had meant getting the job done amid constant distractions. While mentally fashioning an extravagant Josephine Baker ensemble in his head, a preoccupied Minnelli was often jolted back to reality by a boisterous cab driver or too inquisitive waitress. In other words, New York was about trying to accomplish something while 38 million other people have very different ideas.

girl.”

6

For Vincente, New York had meant getting the job done amid constant distractions. While mentally fashioning an extravagant Josephine Baker ensemble in his head, a preoccupied Minnelli was often jolted back to reality by a boisterous cab driver or too inquisitive waitress. In other words, New York was about trying to accomplish something while 38 million other people have very different ideas.

“Every Second a Heart-Beat . . .”: Corporal Joe Allen (Robert Walker) and Alice Maybery (Judy Garland) share a tender embrace in

The Clock

. “The thing was to tell the story of two people who couldn’t be alone,” Minnelli would say of the film’s young lovers. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

The Clock

. “The thing was to tell the story of two people who couldn’t be alone,” Minnelli would say of the film’s young lovers. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

“The thing with

The Clock

was to tell the story of two people who couldn’t be alone,” Minnelli noted. “There was no possibility of privacy for those two people.”

7

Despite their developing intimacy, Alice and Joe are never really by themselves—they are constantly distracted by Minnelli’s colorful parade of interlopers: Alice’s hyper-conversational roommate Helen (played by Vincente and Judy’s friend Ruth Brady), an eavesdropper eating pie à la mode, Keenan Wynn’s philosophizing drunk, and a scene-stealing eccentric delectably played by Angela Lansbury’s mother, Moyna MacGill.

The Clock

was to tell the story of two people who couldn’t be alone,” Minnelli noted. “There was no possibility of privacy for those two people.”

7

Despite their developing intimacy, Alice and Joe are never really by themselves—they are constantly distracted by Minnelli’s colorful parade of interlopers: Alice’s hyper-conversational roommate Helen (played by Vincente and Judy’s friend Ruth Brady), an eavesdropper eating pie à la mode, Keenan Wynn’s philosophizing drunk, and a scene-stealing eccentric delectably played by Angela Lansbury’s mother, Moyna MacGill.

To all involved, it became immediately apparent that although Zinnemann’s grittier authenticity was forfeited, a romantic warmth and charm were

regained once Minnelli was in the director’s chair. Though Garland doesn’t sing a note, in Vincente’s hands

The Clock

plays like a musical with the numbers excised.

ac

A charming scene in which Joe scrambles after Alice’s 7th Avenue bus almost comes off like a mini-sequel to “The Trolley Song.” And George Bassman’s beautiful underscoring and his use of the haunting British ballad “If I Had You” add another layer of poignancy to this wartime romance.

regained once Minnelli was in the director’s chair. Though Garland doesn’t sing a note, in Vincente’s hands

The Clock

plays like a musical with the numbers excised.

ac

A charming scene in which Joe scrambles after Alice’s 7th Avenue bus almost comes off like a mini-sequel to “The Trolley Song.” And George Bassman’s beautiful underscoring and his use of the haunting British ballad “If I Had You” add another layer of poignancy to this wartime romance.

It was during the filming of

The Clock

that Minnelli and Garland’s own love story reignited. As many at the studio shook their heads in disbelief, Judy and Vincente were once again an item, and this time they were more open about their feelings.

The Clock

that Minnelli and Garland’s own love story reignited. As many at the studio shook their heads in disbelief, Judy and Vincente were once again an item, and this time they were more open about their feelings.

“When I was shooting, she only had eyes for him,” actress Gloria Marlen says of Judy’s obvious affection for her director. “She was constantly following him around and trying to look through the camera to see what he was shooting. They were not married or anything at the time but it was kind of cute, you could see that she had a real crush on him.” Marlen has a memorable bit in the film as a young lady who receives a corsage from a serviceman (“Here’s something to top you off . . .”). This inspires Joe to buy one for Alice. Of her director, Marlen remembers that “he was very patient but noncommittal. I mean, Vincente never said a word. He was very business-like in his approach. He gave very little direction and he assumed a lot with me because it was only my second film and I didn’t know beans about it. . . . I never knew if I had done what he wanted or not.”

8

8

The Clock

opened at New York’s Capitol Theatre in May 1945, and the critics devoted as much column space to praising the film’s director as its stars.

Time

raved: “[Minnelli’s] semi-surrealist juxtapositions, accidental or no, help turn

The Clock

into a rich image of a great city. His love of mobility, of snooping and sailing and drifting and drooping his camera booms and dollies, makes

The Clock

, largely boom shot, one of the most satisfactorily flexible movies since Friedrich Murnau’s epoch-making

The Last Laugh

.”

9

And Manny Farber observed: “

The Clock

is riddled, as few movies are, with carefully, skillfully used intelligence and love for people and for movie making and is made with a more flexible and original use of the medium than any other recent film. . . . Minnelli’s work in this, and in

Meet Me In St. Louis

, indicates that he is the most human, skillful director to appear in Hollywood in years.”

10

opened at New York’s Capitol Theatre in May 1945, and the critics devoted as much column space to praising the film’s director as its stars.

Time

raved: “[Minnelli’s] semi-surrealist juxtapositions, accidental or no, help turn

The Clock

into a rich image of a great city. His love of mobility, of snooping and sailing and drifting and drooping his camera booms and dollies, makes

The Clock

, largely boom shot, one of the most satisfactorily flexible movies since Friedrich Murnau’s epoch-making

The Last Laugh

.”

9

And Manny Farber observed: “

The Clock

is riddled, as few movies are, with carefully, skillfully used intelligence and love for people and for movie making and is made with a more flexible and original use of the medium than any other recent film. . . . Minnelli’s work in this, and in

Meet Me In St. Louis

, indicates that he is the most human, skillful director to appear in Hollywood in years.”

10

The constantly interrupted romance on screen in

The Clock

was mirrored by Vincente and Judy’s own relationship. Life on the lot—especially for two of the studio’s brightest talents—was the ultimate gold-fish-bowl experience. As gossip columnists shared every tender Minnelli-Garland glance with readers around the world, there was no hope for any real privacy. When Judy moved into Vincente’s elegantly appointed house on Evanview Drive in the Hollywood Hills, the couple did everything possible to keep their cohabitation out of the columns. “At that time, there was Louella and Hedda,” Minnelli recalled of the era when all-powerful gossip columnists Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper reigned supreme. “So we had to keep it very quiet. But it leaked out because somebody’s legman lived right across the street.”

11

Before long, studio insiders knew that Judy had moved in with Vincente. There were even rumors that the couple intended to marry.

The Clock

was mirrored by Vincente and Judy’s own relationship. Life on the lot—especially for two of the studio’s brightest talents—was the ultimate gold-fish-bowl experience. As gossip columnists shared every tender Minnelli-Garland glance with readers around the world, there was no hope for any real privacy. When Judy moved into Vincente’s elegantly appointed house on Evanview Drive in the Hollywood Hills, the couple did everything possible to keep their cohabitation out of the columns. “At that time, there was Louella and Hedda,” Minnelli recalled of the era when all-powerful gossip columnists Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper reigned supreme. “So we had to keep it very quiet. But it leaked out because somebody’s legman lived right across the street.”

11

Before long, studio insiders knew that Judy had moved in with Vincente. There were even rumors that the couple intended to marry.

Other books

After the Kiss by Joan Johnston

Love's Misadventure (The Mason Siblings Series Book 1) by Cheri Champagne

Kieran by Kassanna

Resistance (Ilyon Chronicles Book 1) by Jaye L. Knight

Samantha James by His Wicked Ways

I Hunt Killers Neutral Mask by Barry Lyga

Always His (Crazed Devotion #1) by C.A. Harms

The Other Woman's Shoes by Adele Parks

The Popsicle Tree by Dorien Grey

One Chance: A Thrilling Christian Fiction Mystery Romance by Daniel Patterson