Miracles of Life (26 page)

Authors: J. G. Ballard

MystFest was interesting to me because it demonstrated

the peculiar psychology of the jury system. The six jurors,

with Claire as supernumerary, enjoyed our meals together in

Viareggio’s best restaurants, including Puccini’s favourite. It

seemed to me that we were in agreement about everything,

sharing the same taste in films, whether European, Japanese

or American. I was sure we would come to a speedy conclusion when we sat down to decide on the winner.

Halfway through the festival, when we had seen five films,

Jules Dassin called a meeting. ‘The films are rubbish,’ he told

us. ‘We’ll give the prize to Roeg.’ We had not yet seen Roeg’s

film,

Cold Heaven

, and I pointed out that there were six films

waiting to be screened for us. ‘They’ll be rubbish too,’ Dassin

said. I suspect that he was under pressure from the festival

management to steer the best film award to Roeg. Bob

Swaim, the American director of

Half Moon Street

and

La

Balance

(‘I always sleep with my leading ladies.’ This left me

agog. ‘You’ve had sex with Sigourney Weaver? Tell me more.’

‘No, not Sigourney.’) and I insisted that we see all the films,

though the other jurors were ready to follow Dassin.

In the event, sadly, Roeg’s film was not one of his better

efforts, and at our final meeting Dassin gave up his attempt

to award the prix d’or to him. But our problems had only

just begun. As we discussed the eleven films it soon became

clear that we would never agree. Each member of the jury

had his or her favourite, which the other jurors dismissed

with contempt. We stared at each speaker as if he had

announced that he was Napoleon Bonaparte and was about

to be taken away by the men in the white coats. Every choice

other than my own seemed preposterous. I assume that sitting

collectively in judgement runs counter to some deep

and innate belief that justice should be dispensed by a single,

all-powerful magistrate. How jurors at murder trials ever

come to a unanimous verdict is beyond me.

Aware that we were becoming tired and fractious, Dassin

wisely called a halt to the discussion. He passed around

pieces of paper and asked us each to write down our top

three films, in descending order. This we did, and it is

remarkable that the eventual winner did not feature in the

list of any member of the jury.

Utter deadlock loomed, and tempers rose. No one was

prepared to yield an inch. We were saved by one thing alone

– our desperate need for lunch. We were tired, angry and

starving. At last we seized gratefully on a compromise candidate,

a German thriller about a Turkish detective in Berlin.

This had been shown without subtitles, and had been barely

comprehensible. But it would have to do.

The German woman director was flown in for the prize-

giving but the festival organisers were most displeased.

Roeg’s honour was satisfied, though not in the way we had

expected. At the gala evening, in front of massed TV cameras

and journalists, we found that our deliberations had been

demoted to the status of a ‘jury’ prize. The festival grand

prix, newly created for the occasion, went to Nick Roeg. As

the jury retreated from the rear of the stage, well aware of its

humiliation, I wished that we had heeded the wise old Jules

Dassin and awarded Roeg the prize in the first place.

My novel

The Kindness of Women

, a sequel to

Empire of

the Sun

, was published in 1991, and the BBC TV series

Bookmark

decided to make a programme about my life and

work. Most of it was filmed in and around Shepperton, but

I spent a week in Shanghai with the film crew and its director,

James Runcie. He was the son of the then Archbishop of

Canterbury, which may have had some bearing on the help

that the Chinese gave us. Two English-speaking executives

from the Shanghai television service were with us throughout

the week. I have no doubt that part of their job was to

keep an eye on us, but they went out of their way to lay on

an air-conditioned bus and car and smooth our path around

any obstacles.

Without their navigation skills we might never have discovered

Lunghua Camp, now completely swallowed by the

urbanisation of the surrounding countryside. In the 1930s

our house in Amherst Avenue had stood on the edge of the

western suburbs of Shanghai. Standing on the roof as a boy, I would look out over the cultivated farmland that began

literally on the far side of our garden fence. Now all this had

gone, vanishing under the concrete and asphalt of greater

Metropolitan Shanghai.

The return to Shanghai, for the only time in forty-five years,

was a strange experience for me, which began in the Cathay

Pacific lounge at Heathrow. There I saw my first dragon

ladies, rich Chinese women with a hard, fear-inducing gaze,

similar to those who had known my parents and terrified me

as a child. Most of them got off at Hong Kong, but others

went on with me to Shanghai. We landed at the International

Airport, on one of the huge runways laid across the grass

airfield at Hungjao where I had once sat in the cockpit of a

derelict Chinese fighter. As the dragon ladies left the first-

class compartment their immaculate nostrils twitched disapprovingly

at the familiar odour that stained the evening

air – night soil, still the chief engine of Chinese agriculture.

We drove into Shanghai down a broad new highway.

Lights glimmered through the perspiring trees, and above

the microwave air I could see vast skyscrapers built in the

1980s with expat Chinese money. Under Deng’s rule,

Shanghai was returning rapidly to its great capitalist past.

Inside every open doorway a small business was flourishing.

A miasma of frying fat floated into the night, radio

announcers gabbled, gongs sounded the start or end of a work shift, sparks flew from the lathes of a machine shop,

mothers breastfed their babies as they sat patiently by pyramids

of melons, traffic horns blared, sweating young men in

singlets smoked in doorways … the ceaseless activity of a

planetary hive. There are only two words in the Chinese

bible: Make Money.

The Bund was intact, the same vista of banks and trading

houses still faced the Whangpoo river, crowded with ships

and sampans. The Nanking Road seemed unchanged,

Sincere’s and the great Sun and Sun Sun department stores

crammed with Western goods. The racecourse was now an

immense parade ground, the only visible trace of the

authoritarian regime. I had hoped that we might stay at the

former Cathay Hotel (now the Peace Hotel) on the Bund, a

crumbling art deco palace. We later filmed a scene in the

karaoke bar, where drunken Japanese tourists bellowed their

way through Neil Diamond hits. But the Cathay, where Noël

Coward had written

Private Lives

, lacked fax links to the

outside world, and we moved to the Shanghai Hilton, a tall

tower not far from the former Cathedral Girls’ School.

Memories were waiting for me everywhere, like old

friends at an arrivals gate, each carrying a piece of cardboard

bearing my name. The next morning I looked down at

Shanghai from my room on the seventeenth floor of the

Hilton. I could see at a glance that there were two Shanghais

– the skyscraper city newer than yesterday, and at street level

the old Shanghai that I had cycled around as a boy. The Park Hotel, overlooking the former racecourse and a vast brothel

for American servicemen after the war, had been one of the

tallest buildings in Shanghai, but was now dwarfed by gigantic

TV towers and office buildings that stamped ‘money’

across the sky. The Hilton stood on the edge of the old

French Concession, still today one of the largest collections

of domestic art deco architecture in the world. The paint-

work was shabby, but there were the porthole windows and

marina balconies, fluted pilasters borrowed from some car

factory in Detroit in the 1930s. Curiously, the TV towers,

broadcasting the new to the people of Shanghai, seemed

rather old-fashoned and even traditional, as seen everywhere

from Toronto and Tokyo to Seattle. At the same time, the

dusty and faded art deco suburbs were bracingly new.

I was due to rendezvous with Runcie and his crew at

9 a.m. in the Hilton lobby, but an hour earlier I slipped out

of the hotel and began to walk the streets, heading in the

general direction of the Bubbling Well Road. The pavements

were already crowded with food vendors, porters steering

new photocopiers into office entrances, smartly dressed

young secretaries shaking their heads at a plump and sweating

60-year-old European out on some dishevelled errand.

And I was on an errand, though I had yet to grasp the true

nature of my assignment. I was looking for my younger self,

the boy in a Cathedral School cap and blazer who had played

hide-and-seek with his friends half a century earlier. I soon

found him, hurrying with me along the Bubbling Well Road, smiling at the puzzled typists and trying to hide the sweat

that drenched my shirt. On the last leg of our journey from

England, as we took off from Hong Kong, I worried that I

had waited too long to return to Shanghai, and that the

actual city would never match my memories. But those

memories had been remarkably resilient, and I felt surprisingly

at home, as if I was about to resume the life cut off

when the

Arrawa

set sail from its pier.

But something was missing, and that explained the real

nature of my breakfastless errand.

Shanghai had always been a European city, created by British

and French entrepreneurs, followed by the Dutch, Swiss and

Germans. Now, though, they had gone, and Shanghai was a

Chinese city. All the advertising, all the street signs and neon

displays, were in Chinese characters. Nowhere, during our

week in Shanghai, did I see a single sign in the English language,

except for a huge hoarding advertising Kent cigarettes.

There were no American cars and buses, no Studebakers and

Buicks, no film posters in twenty-foot-high letters announcing

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Robin Hood or Gone

With the Wind

.

Shanghai had forgotten us, as it had forgotten me, and the

shabby art deco houses in the French Concession were part

of a discarded stage set that was slowly being dismantled.

The Chinese are uninterested in the past. The present, and a modest down payment on a first instalment of the future, are

all that concern them. Perhaps we in the West are too preoccupied

with the past, too involved with our memories,

almost as if we are nervous of the present and want to keep

one foot safely rooted in the past. Later, when I left Shanghai

and returned to England with Runcie and the film crew, I felt

a great sense of release. I had visited those shrines to my

younger self, stood in silence for a few moments with my

head bowed, and driven straight to the airport.

At 9 on that first morning we gathered in the Hilton lobby

and then set off for the Ballard home in the former Amherst

Avenue. The house was still standing, though in a state of

extreme dilapidation, its gutters propped up by a scaffolding

of bamboo poles that was in turn about to collapse. At the

time of our visit the house served as the library of a state

electronics institute, and metal book-racks filled with international

journals and magazines had replaced the furniture

on all three floors, a change that might have pleased my

father. Nothing, otherwise, had changed, and I noticed that

the same lavatory seat was in my bathroom. But the house

was a ghost, and had spent almost half a century eroding its

memories of an English family that had occupied it but left

without a trace.

The next day we set off in our air-conditioned bus for

Lunghua, and spent most of the morning trying to track it

The former Ballard house in Amherst Avenue, Shanghai

,

in 2005. The fountain, garden sculpture and wall

decoration are recent additions

.

down. A vast urbanised plain stretched south from the

Shanghai that I had known, a haze-filled terrain of flats,

factories and police and army barracks, linked together by

motorway overpasses. Now and then we stopped, and

climbed to the roof deck of a workers’ apartment block,

where I scanned the countryside for any sight of the water

tower. Eventually, one of our translators hailed an old man

dozing outside a bicycle shop. ‘Europeans, imprisoned by the

Japanese…?’ He thought about this. ‘There was a camp – I

don’t remember which war…’

Ten minutes later we arrived at the gates of the former

Lunghua Camp, now the Shanghai High School. Almost

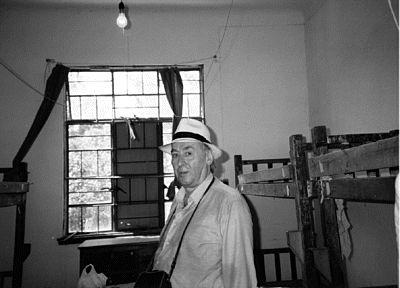

Standing outside the former G Block in 1991

.

The Ballard family room in the former G block

.