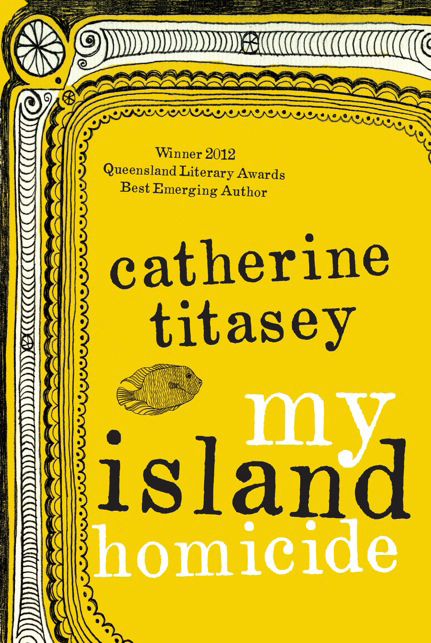

My Island Homicide

Read My Island Homicide Online

Authors: Catherine Titasey

Catherine Titasey was born in Sydney, raised in Papua New Guinea and travelled widely with her family and as a young adult. She studied law

at The University of Queensland

and then worked

as a solicitor before taking an extended overseas adventure that ended on Thursday Island, a multicultural community in the Torres Strait. There she fell in love with Tony, a local fisherman.

They have six children. In 2012, Catherine won the Queensland Literary Award for Emerging Queensland Author for this novel.

For more information, see

www.catherinetitasey.com.au

.

For Tony

I do not think that many people have been to Thursday Island. It is in the Torres Straits and is so called because it was discovered on a Thursday by Captain Cook. I went there since they told me in Sydney that it was the last place God ever made. They said there was nothing to see and warned me that I should probably get my throat cut.

French Joe

, W. Somerset Maugham

Chapter 1

Mr Tamala's left eye was swollen, a swirl of purple and red, vibrant against his dark skin. His right eye was untouched and seemed to work twice as hard to compensate, opening with emphasis, narrowing with mistrust, darting between his wife and me as he conveyed his point. I wanted to cry, but it wouldn't look good â the new boss crying on her first day of work, April Fools' Day, no less. At that moment, I regretted taking this officer-in-charge position on remote Thursday Island. I had wanted a radical life change, one that would deliver a relaxed and uncomplicated life in the tropics. Instead, I had Mr and Mrs Tamala in my office.

I glanced at the government-issue clock above the doorway. Husband and wife had been trying to convince me for 23 minutes that a serial killer was on the loose on the island. Apparently I had to act before more people died. The killer was using

maydh

, otherwise known as black magic. Mr and Mrs Tamala accused Danny Soto, 27, a labourer of John Street, of making

maydh

and causing people either to pass away from illness or meet a tragic demise. I toyed with the idea of telling them Danny would be charged with Procuring Death Using Forces of Darkness and he'd feel the full weight of the white fella's law.

Before the Tamalas arrived to lodge their complaint, I had a quick read of the QP9, the document detailing the facts of the assault. Danny admitted to the arresting officer that he had flogged Mr Tamala, saying he was fed up with being accused of âstupid native black magic'. The QP9 quoted him as saying, âWhat does Tamala expect? People to live forever?'

âDanny has been charged with assault,' I said, trying not to stare at Mr Tamala's giant weeping eye. âAnd his bail conditions mean he can't come near you or contact you.'

âWell, that's a fat lot of good,' said Mr Tamala. âHe doesn't need to come near me to kill me.

Yu mas sabe maydh, my gel

.'

Mr Tamala was having a crack at me for not knowing my culture. Unlike him, I have one European parent, my father, and I was born and raised in Cairns. To be honest, I don't even know what my Islander mother thinks about

maydh.

We've never talked about it and never had to because down south we know people die from accident, illness or old age.

I opened my mouth to say the Queensland Police Service was ill-equipped to deal with complaints of sorcery.

âYou probably don't even know Broken English.' Mr Tamala leaned as far forward as his barrel belly allowed and raised the hairy eyebrow above his good eye.

I took a deep breath, intending to offer Mr Tamala a brief explanation of the legal process.

âWell, do something,' he hissed.

I'd learnt from the two-day cross-cultural induction seminar I'd attended before coming here that Indigenous people are quiet and non-confrontational. That is the case with my Islander mother and my aunties and most of the relatives who have stayed with my family over the years. We were told, by the Islander and Aboriginal facilitators, that when asked a question, Indigenous people may pause so long it's easy to think they are not going to answer. So we were warned to accept silences and wait for people to speak. But it seemed I couldn't get a word in with Mr Tamala.

âPeople are dying because of him. Isn't that right, Sissy?'

âYes,

bala

,' said his wife, nodding at me. She wore the national dress of the Torres Strait: a bright floral-print âisland dress'.

âYouse police should do something.' Mr Tamala was gasping for breath as he spoke. Sweat formed on his forehead, which he wiped every now and then with a

sweater

, a handtowel worn by Islanders over the shoulders. I was worried he might have a heart attack in my office. Then I realised that might work in my favour. And Danny Soto's.

âAnd how are these people dying, Mr Tamala?'

âHuh? Don't speak so fast.'

âSorry, how are these people dying?'

âSo now you believe me.' He leaned back in triumph. âThey are having heart attacks and strokes. They are dying in accidents. Jacky Witt drowned in February. Nula Benton died a fortnight ago. And then there's Willis Banes.'

I was about to protest, but stopped myself in time to consider what I knew. Chronic disease caused by poor lifestyle was responsible for many premature deaths in the Torres Strait. Jacky Witt did drown in February and a week-long search and rescue failed to recover his body or dinghy. I knew this because it had been reported on the local ABC radio in Cairns. There had been deep fears for his safety given he was heavily intoxicated at the time he headed out, his dinghy had major mechanical problems and there was a strong wind warning. Any rational person would attribute his death to misadventure rather than

maydh

.

I knew about Nula Benton's death too, thanks to Jack Lakoko, the dashing Islander sergeant who collected me from the ferry yesterday with his dog, a huge brindle thing that kept farting. Nula was Jack's cousin. As he took me on a âround' of the island, managing just once to get into fourth gear for less than a kilometre, he laughed about the rumour that Nula's death had been the result of

maydh.

âHer liver packed it in, finally. Doctors told her for years to knock off the Bundy,' said Jack, with a killer grin that could melt the hearts of most women. He reckoned Nula had laughed about cheating death all those years. âSometimes people use

maydh

as an excuse,

wat

,

yu sabe

, for bad things happening. Not with Nula. Other times

maydh

really is the reason for them.'

But the Willis Banes bit threw me. I had never heard of him. âEnlighten me.'

âHuh?' said Mr Tamala.

âWillis Banes, what happened to him?'

âHe died in a car accident,' said Mrs Tamala.

âA car accident? On Thursday Island?' That I didn't believe. There was only five kilometres of ring road.

âNo, in Townsville.'

âSo, how do you know Danny was involved?'

âWillis been beat Danny in the pool comp at the Railway Hotel, here on TI, two weeks before Willis been dead. Danny was wild.'

I didn't mean to, but I closed my eyes and sighed. My eyes shot open when the phone rang. I answered it, hoping for a life-threatening emergency. But it was just the constable, who sounded the whole of 13 and three-quarters years old. She was after the detective, Jenny, but had pressed five instead of two. In that brief exchange, my eyes fell to my desk calendar.

Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.

A Chinese proverb. Of course. This was all an April Fools' prank! The Tamalas and their black magic claims were a set-up. I glanced through the doorway, seeking out staff with mischievous grins. Jack was walking past, mobile to his ear. He winked at me and gave me the thumbs up. Ha! I rest my case!

âOkay,' I said, keeping the handpiece to my ear even though the constable had hung up. âThat sounds serious. I'll come right away.'

I shook my head, trying to look as solemn as possible.

âWhat's happened now?' asked Mr Tamala. âSomething to stop you jailing Danny Soto, I bet?'

âI'm afraid I have to go. An emergency has come up.'

âYou will do something?' asked Mr Tamala.

âYes, of course.'

He and his wife heaved themselves up.

I walked them to the door, determined to see them out. After they left, I leaned my forehead against the shiny sign on my office door.

SENIOR-SERGEANT EBITHEA DARI-JONES

OFFICER-IN-CHARGE

If I wasn't the victim of a silly prank, I was stuck on a small remote island on my first day of a two-year contract, dealing with a couple of superstitious overweight locals who wanted me to arrest a black magic serial killer. I really did want to cry.

Chapter 2

âAre you crying?' asked a squeaky voice behind me, dripping with disgust.

I lifted my forehead from the plastic sign, the edge having dug a little into my skin. It was the constable â I saw from her name

tag â her white blonde hair shiny like two-pack epoxy. She stood a

few metres from me, as if I was carrying the plague. She clutched a file to her chest.

âOf course not,' I said. âI was thinking.'

âChoice. I thought you were having a breakdown or something.' Her sickly sweet perfume was overpowering.

âThea Dari-Jones.' I held out my hand and she shook it. She had those damn fake nails with glowing white tips.

âYou've got a red line on your forehead.'

âThat's what happens when I think too hard. You are Shayelle Connors?'

âYeah,' she said. âShay.'

âAnd what have you got there, Shay?'

âOh, this? It's a missing person's report.'

I laughed. Missing on TI? How ridiculous. Then I realised the missing person's report must be a person missing at sea, because there were famously a few of those each year. Just like Jacky Witt.

âThat'll be missing at sea?' I asked with great confidence.

âSea? Nuh. On the island.'

âDon't you think it's a bit of a coincidence that someone would go missing, today of all days?' Clearly, Shay wasn't in on the joke.

âCoincidence? I dunno. I've only been here three months.'

âLeave it with me,' I said, pointing to the two skyscrapers of folders on my desk. When I looked back, she was still standing there, her head cocked to one side, like a chook. âYou can go now.'

âCool.'

This was going too far: first sorcery, now a missing person. One caper was fine, two tedious. It was still only 9.45am on my first day. I took a deep breath as I had been taught in my yoga classes, closed my eyes and focused on a positive experience: waking up this morning.

Too excited to sleep, I rose in the cool tropical morning and stood on the verandah of my beach-front unit. I could not help smiling as I gazed at the emerald islands rising from the ocean. For breakfast I ate freshly picked pawpaw from my small backyard and a banana from the bunch given to me by my neighbour, Maggie. She was mid-fifties, small and wiry, with spiky grey hair and a sapphire stud in her nose. She'd called in yesterday after Jack dropped me off.

âHere's a welcome to TI gift,' she said, holding out a hand of sugar bananas. âYou're Islander?'

âNo, yes, sort of. My first time on the island, though. I'm the new OIC of police.'

âSocial worker, Queensland Health. Another white public servant blowing through,' she said matter-of-factly. âYou'll want to settle in, unpack. Give me a hoy if you need something.'

I savoured the fresh fruit for breakfast and embraced my new laid-back life as officer-in-charge, Thursday Island. I even had time to do some yoga. I laid out my purple bubble mat and performed a few salutes to the sun. I saluted my new beginning and the magnificent seascape beyond the sliding glass doors of my lounge room. While I stretched and bent, and tucked and arched, I thought that I was much better off without Mark, that catching him six months ago in our bed with his young assistant (a fancy name for his secretary) wasn't such a bad thing after all.

I was desperate for the simplicity of life TI offered and I knew I had made the right decision, even when I walked into the small brick station, with paint peeling from my office ceiling and vinyl chairs split with age to reveal the sponge beneath and a chipboard bookshelf sagging under the weight of cardboard folders, yellowed with age. The bags of used clothing and boxes of children's books in the corner of my office only intrigued me.

The first thing I did when I got to work, before Mr and Mrs Tamala arrived, was set up my desk. To the left, I put the photo of my family taken at my mother's 69th birthday last year. Dad, fair-skinned and silver-haired, next to Mum, the colour of milk chocolate with cropped curly hair. My two older brothers, Thomas and William, and I were coloured midway between our parents, a light brown. In fact, the exact brown of a tropical estuary flooded with wet season rain. To the right, I put the desk calendar, which I kept mostly for the daily quotes. Thank God for that desk calendar, otherwise I would have fallen for both pranks.

I had penned in Mick Buckrell, the departing senior-sergeant, for a nine o'clock handover and he was almost an hour late. Before I had time to ask Shay or Jack Lakoko, I was startled by loud abuse from the foyer. I rushed out to discover a massive woman trying to dodge past Jack to get to a smaller man behind the foyer gate. I'm six feet tall, but this woman was taller than me and twice as wide. Her head merged with her shoulders in a giant roll of flesh.

âWant a hand, Jack?' I asked. He could have featured in one of those men-in-uniform calendars with his broad shoulders, dark skin and almond-shaped eyes, the kind genetic bequest from a Japanese ancestor.

â

Yu fucken big munee

.

I go drill you.

Yu koey nutta

.' The woman yelled more abuse in the traditional Islander language I didn't understand.

âNah, she'll be right,' Jack said in a calm voice as he winked at me. âStop! Party's over.'

The woman actually stopped, but her chest kept heaving.

âIt's okay, Mrs Bintu,' said Jack. â

Yu matha go haus now

.'

Mrs Bintu shook her fist at the small man, stuck her chin out to Jack with a scowl and walked out. I couldn't believe it. A police officer said stop and the potential offender not only stopped, but left quietly.

Jack straightened his shirt. âIt's a long story, Thea,' he said, gesturing to the man. âMrs Bintu been

daylight

last night, gambling on triple leaf,

yu sabe

, cards, and used the food money that was supposed to last till pension day, next Thursday. So Mr Bintu hit her.

Em

here for protection.'

âYeah,' said Mr Bintu. âFuckin' bitch.' His T-shirt was faded and the neckline fraying.

âTake a seat,

bala

. I'll get you a cuppa.' Jack headed off, and I followed.

âWhat was she yelling to her husband?'

âStuff.'

âWhat stuff?'

âYou don't want to know.'

âJack, I wouldn't have asked if I didn't want to know.' He flicked on the kettle in the kitchen. âJack?'

âShe was abusing him.'

âYou don't say.'

âNo, seriously, she

was

,' he said with wide-eyed innocence. âThat's what they do when . . .'

âJack, I know. Just translate for me.'

âShe was calling him . . . female . . . she was insulting him using female . . . private parts.'

âGee, that's just what we do in Western culture. Does this charade happen often?' I asked.

âEvery couple of months. There's history to the Bintus and it doesn't take much for us to settle things down. Keep things out of court,

wat

. The old boss, Mick, was all for it.'

âRight,' I said, not wanting to interfere with due process. âSo, you'll sort Mr Bintu out and I'll get back to work?'

âYeah, she's all peaches.'

âYou mean apples?'

âHuh? Whatever, it's all fruit.' He rushed after me. âThea, do you want a dog?'

âNo.'

âJoey needs a home. You met him yesterday when I picked you up.'

âI thought he was your dog.'

âNo, one of the teachers wanted a second dog, company for her Jack Russell. I was taking Joey around to meet them. But Joey was a bit bigger than she expected. Interested?'

âNo.'

âSingle woman needs a man in her life to keep her safe.'

âNo.'

âOkay, okay. If you change your mind and he's already gone, you'll regret it.'

âI can only hope so.'

Sorcery and homeless farting dogs aside, I had to focus on the positives and remind myself why I came here. Before applying for this position, I'd done my research. I quizzed past officers and three former OICs. I checked statistics. Although Indigenous people are more likely to offend than non-Indigenous, most offences in the Torres Strait involved alcohol, which resulted in assault, property damage, traffic violation, public drunkenness and domestic violence. There were a few drug matters, serious assaults like grievous bodily harm and sexual assaults, but these were exceptions to the rule. Most offending was between parties known to each other, was opportunistic and was nothing like the serious crime I was used to. The incident with the Bintus was a pleasant confirmation of my research. It was just what I needed since I'd become bitter and twisted after 19 years of policing violent crime, seeing countless bodies carved up, blasted apart, burnt or decayed.

Once quiet resumed, I returned to my office and flicked through back copies of the

Torres News

that were piled in a Tully Bananas box. I intended to dump the lot, but I wanted to have a quick read of a few papers first. You can pick up a lot about a community from the local rag. I found that out when I worked as a constable in country towns west of Brisbane in the early nineties. I became an auxiliary firefighter and went to line dancing classes and rodeos, all because I answered classifieds in the local paper. At one of the rodeos I met a handsome Elders sales rep and spent five wonderful days in Toowoomba with him . . . until he told me his girlfriend was visiting from Roma the next day.

Anyway, in the

Torres News

was a semi-regular Crime Stoppers column, semi-regular because there simply wasn't enough unsolved crime on TI. It did give me a snapshot of what unsolved offending had occurred: mostly stolen bikes, and theft of food from school tuckshops and grog from bottle shops. I noted in the past three months there had been five occurrences of sexual assault on women around Millman Hill, which I guessed was a suburb.

Articles about search and rescues all had happy endings apart from Jacky Witt's, which was in February's edition and came with a half-page spread on boating safety.

There were ads and articles in each edition encouraging people to enrol at TAFE and to gain qualifications in Business Administration and Coastal Marine Operations â Coxswain Certificate.

My favourite column to read was the Letters to the Editor, which appeared to be the channel for people to vent their frustrations to the general public without actually confronting anyone directly. Each week, one man lambasted readers for straying from the word of the Lord and used anything from footy games to 21st parties as proof of blasphemy. There were a few letters about the high cost of living, the president of the school P & C Association complaining about lack of parental and community commitment, and many complaining about stray dogs; one man wrote that âthe council by-laws with respect to animal management should operate in the Torres Strait because, and this may come as a surprise to many people, the Torres Strait is part of Australia'.

Hear, hear

, I thought. This was exactly what I expected in a small island community.

I was intrigued by the letters written by Arthur Garipati, who signed off

Chief Mamoose of Torres Straits

. Each week, he urged workers to ârise up against the oppressors, claim your rights to legal and cultural autonomy' and to âsend Europeans home so not to tolerate any longer the unreasonable, oppressive and repressive governmental control'. Two weeks later he accused white public servants of only coming to the âTorres Straits' for the âjoyous benefits of their jobs' and demanded âmore money be given to the Torres Straits'. I couldn't quite understand if he was encouraging people to reject capitalism, which was limited on an island sustained by the three tiers of government, particularly welfare, or whether he was having a go at the government, which you wouldn't do if you wanted more funding. I couldn't understand the gist of his letters at all, but I wouldn't have minded some of those âjoyous benefits' that didn't come with my salary package. Perhaps he was just showcasing an expansive vocabulary.

I put the papers away when Lency Edau, station receptionist, dropped in to introduce herself. I'd liaised by phone with Lency for the past five years while I was working in Cairns. Serious matters in the Torres Strait like violent assaults, rapes and child sexual abuse are referred to the District Court in Cairns for trial if the defendants plead not guilty. Officers from TI and Cairns liaise about documents, witnesses, exhibits and court dates. Lency told me a couple of years back that her great-grandmother was related to my mother's cousin's great-aunt. I checked with Mum who said her cousin's great aunt, Aka Velma, had been traditionally adopted into the family about 60 years ago. I was thoroughly confused, but when Lency came into my office after ten, she crushed me in a tight hug as if I really was a long lost relative.

âI had to take my great-grandson to the specialist's clinic. I've just dropped him back to the babysitter,' she said, looking me up and down. âAnd you do look just like Aka Velma, but more taller.'

Lency's giggle was infectious and I found myself smiling. I couldn't believe that a great-grandmother could be so energetic and have such smooth skin. Hell, apart from a few streaks of grey around her temples and lines on her face, she didn't look much older than me. A hibiscus was stuck behind her ear. She, I decided, was the product of relaxed island life, and I considered wearing a hibiscus behind my ear tomorrow.

âYou met Jack?

Mina kind

handsome. And Shay? Good. She's new and is in,

wanem

, culture shock. Jenny's not in till later. Met Salome? No? She's the police liaison officer. She is my husband's cousin's husband's daughter. She's on leave, taken her latest boyfriend out to family on Yam Island. She likes those white men, the tradesmen, especially Bertie the builder's men.' I was hoping she didn't want answers because I'd forgotten her first few questions already. âSo you're all settled then?' She squeezed my arm.