My Share of the Task (29 page)

Read My Share of the Task Online

Authors: General Stanley McChrystal

Soon the young man began to grow a beard and wear different clothes. He started praying five times a day. It felt good to have the rigid discipline, the direction, and to think of himself as a hard man. In many ways he appeared no different from hundreds of millions of devout, peaceful Muslims. But the ideas he imbibed were narrow and potent. For some in the group with guilt over a wayward youth, jihad offered redemption, as it had for Zarqawi, who had ruined his adolescence with drugs and gangs. Soon the young man had no friends outside this circle. If the recruiter introduced the young recruits to a jihadist just back from Iraq, they would envy the older, prouder bearing of this veteran. One day, the young man came to the mosque and found that a handful of regulars were absent. It had been their turn. Violent jihad became not just a pillar of the particular faith preached to the young man's group. It was now compulsory as a source of esteem in his enclosed world. With a companion, or a maybe a few friends from the mosque, the young man decided to set out for Iraq.

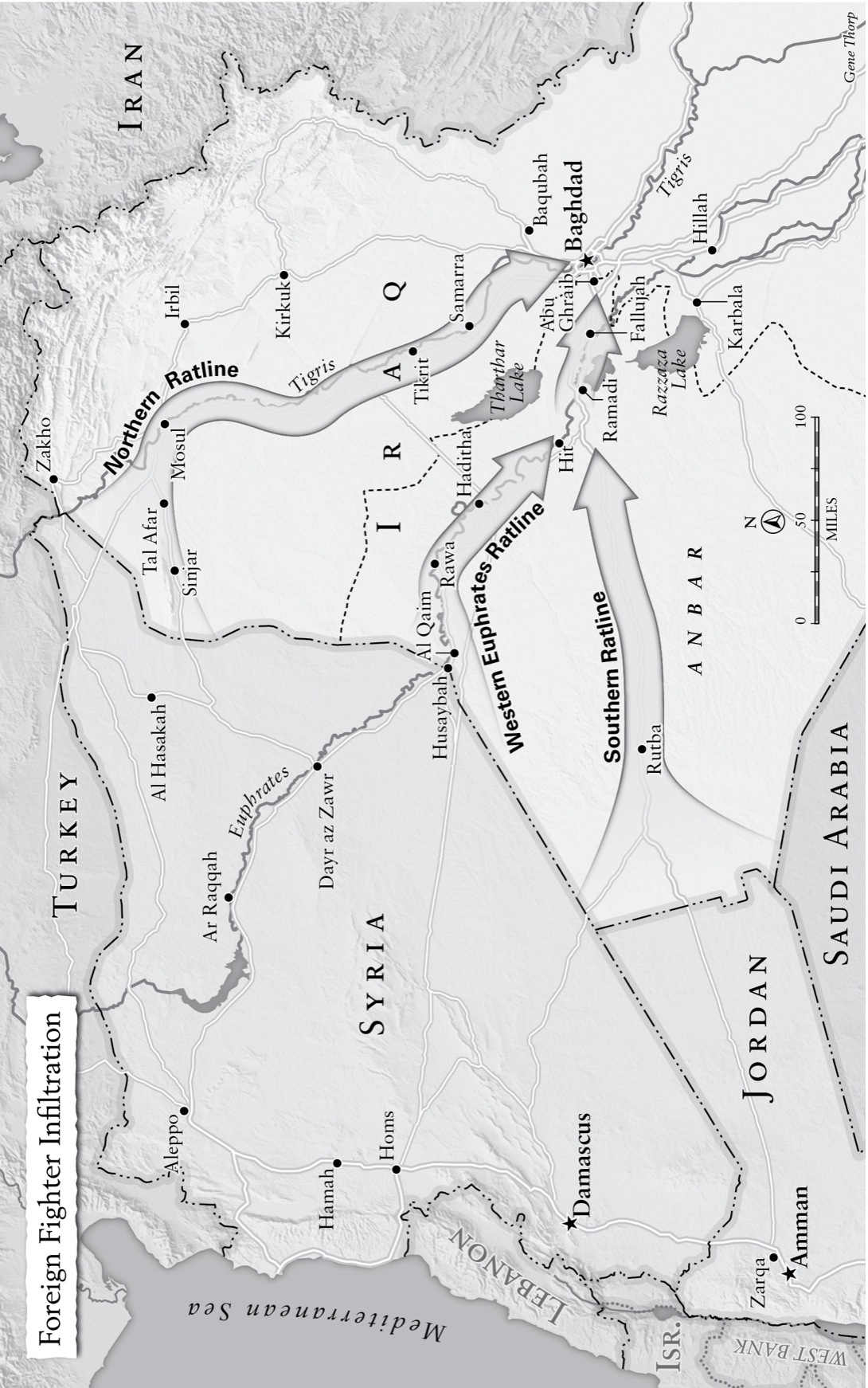

We found that most jihadists entered Iraq through Syria. Using their own savings or money from a wealthy sponsor, they typically flew into Damascus with little more than a gym bag of clothing. From the airport they were split up and rapidly put into what we called ratlines that moved them through safe houses in Syria. Usually passed between single recruiters, not teams, the jihadists moved up to Aleppo, then gradually down the Euphrates through Dayr az-Zawr to the Syrian side of the border, just across from the industrial town of Al Qaim, Iraq. After nightfall, a taxi deposited them at crossing points thirty miles up and down around Al Qaim, and they crossed the final few hundred yards on foot.

Once in Iraq, handlers whisked them to safe houses and confiscated nearly everything. They took volunteers' donations to Zarqawi's organizationâsometimes only a handful of bills, but usually hundreds,

if not thousands, of dollars. AQI kept meticulous records during this intake. The questionnaire we later recovered revealed the enemy had a serious, sophisticated managerial concern with the integrity and breadth of its network. Because its ratlines in Syria tended to rely on paid criminal smugglers, not true believers, AQI asked jihadists what fees the handlers had extracted and how well

they had been treated. To plumb potential partners, AQI had recruits list which other “mujahideen supporters” they knew and

how strong their relationships were.

At these early way stations, the handlers sorted the jihadists. Nationalities appeared in spurts and cycles, though Saudis were the largest, most consistent contingent. Men with visible smarts or a science background might go to Mosul to help make bombs. But handlers would be most anxious to gather those who volunteered to be suicide bombers or peel away those who appeared vulnerable enough to be turned into them.

Inside Iraq, potential suicide bombers were normally handled like rounds of ammunition, moved from safe house basement to safe house basement. Expedited down the pipeline, they were sequestered from outside contact and constantly indoctrinatedâall to prevent them from changing their mind. By design, often the first time a suicide bomber saw Iraqis in the flesh was in the moments just before he killed them.

Attacks were carefully orchestrated. The operative who was to film the 2000 attack on the

USS

Cole

overslept. Zarqawi brooked no such risks. On nearly every suicide bombing, a car with a videographer trailed behind. To safeguard against last-minute hesitation, the follow-on car or a lookout on the street often controlled detonation. In some cases the driverâlike the Saudi behind the wheel of a fuel truck that exploded in Baghdad on

Christmas Eve that yearâdid not know his was a suicide mission. But, at least early in the war, most went willingly. In many of the videos filmed on the day of an attack, the men appeared almost ecstatic.

Periodically, we had information that young men were planning to martyr themselves. The messages they left behind were chilling harbingers of attacks we often could not prevent. There was no humanity or humor in anything surrounding a young person willing to blow himself up to kill innocents. But I had to smile when I saw one message to a mother and read her stern response: “Stop this foolishness now and get your rear end home and back to work.” I hoped the young man complied. There was no way to know.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

D

uring the last week of November 2004, as the second battle of Fallujah waned, I invited General Casey and key members of his Multi-National ForceâIraq (MNF-I) staff to our compound at Balad to discuss our concerns over the foreign-fighter flow.

Although I had a good relationship with George Casey, I was glad that he brought his operations officer, Major General Eldon Bargewell. I'd known Eldon since we were captains at Fort Benning. A highly decorated Vietnam veteran, Eldon and I had worked together many times in later years during his service both in Green and on the TF 714 staff. Eldon was unfailingly helpful in smoothing tensions between MNF-I and TF 714. The setup of our two headquarters invited friction: Although we fought in Iraq, TF 714 answered to CENTCOM, not to MNF-I. Meanwhile, the ground-holding commanders' occasional annoyance with TF 714âover disruptive targeting missions in their domain or our greater share of resourcesâall percolated up to MNF-I headquarters. By being there, Eldon could translate our mission and culture to those he served with on the conventional side.

In the long meeting, Mike Flynn and some of our best minds, like Wayne Barefoot, laid out the case for the threat this foreign flow presented. I was disappointed at how much our read on the enemy differed from that of some of Casey's key staff. One senior officer on the MNF-I team

openly doubted our assessment of AQI's central role in the insurgency.

I sympathized with the concern that emphasizing the role of foreign fighters could be a way to unintentionally sidestep the reality that Iraqis were, in large numbers, joining the insurgency motivated by earthly grievances, not religious jihad. Especially early in the war, we in TF 714 and much of the rest of the Coalition problematically used “AQI” as a catchall designation for any Sunni group that attacked Americans or the Iraqi government. In truth,

more than fifty named insurgent groups fought at one time or another. These distinctions were important but also could be misleading. By numbers, AQI never constituted the majority of the insurgency. But AQI usurped the insurgency's leadership and gave it direction and shapeâoften through sheer intimidation. So while in 2004 and 2005 an Iraqi fighting for a nominally nationalist group did not consider himself a card-carrying member of AQI, his group was fighting within Zarqawi's strategic framework. The insurgent groups were like local gangs, while AQIâricher, crueler, and better linked across the countryâwas the mafia.

No major MNF-I orders or initiatives flowed from that November meeting at Balad, but our discussions continued. Unfortunately, the thinking at our respective headquarters continued to diverge. Around the time we met with George Casey and his staff, a month before Tom D. and Tres stood up our JIATF to combat foreign influence in Iraq, MNF-I assigned its own Baghdad-based JIATF to target “former regime elements”âessentially

old Saddam apparatchiks.

“The fat, old, jowly Baathist generals holding meetings in hotel lobbies in Amman and Damascus are not controlling the insurgency,” John Christian lamented after the meeting, voicing our collective frustration. “They are not the instigators of violence.” Nor were they the levers to success, despite some of their aggrandizing claims to control the spigot of insurgent attacks.

Although disappointed, I appreciated it was an antidote to groupthink for two major headquarters in the same theater to come up with such different assessments. And we could not fault Casey's staff for eyeing us as a kind of special-interest group. TF 714's global mission was almost entirely directed toward Al Qaeda and its close affiliates. So in Iraq we focused on AQI and its terrorist allies like Ansar al-Sunnah. That narrow lens could produce assessments that inflated Al Qaeda's role. And because threat measurements guided resource allocation, TF 714 had an interest in portraying Al Qaeda as the central enemy. As TF 714's growing credibility gave us greater sway in the war's decisions, I knew we needed to maintain a culture of self-scrutiny and humility, lest we have it wrong. Our divergent outlooks also told me our integration and communication with MNF-I was too weak. This we could, and would, labor to fix. At the conclusion of the meeting, while I felt his staff had it wrong, I sensed General Casey remained unconvinced but open-minded.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

E

very Friday that I was in Iraq, I flew from Balad to Baghdad to meet with General Casey. Periodically, in addition to my operations officer, T.T. (or his replacement, Kurt Fuller), and Mike Flynn, I brought two members of TF 16. I wanted Casey to see the knowledge and commitment that defined the task force.

Most of my travels around Iraq were at night. But flying over Baghdad every week for more than four years gave me a time-lapse-photography-like view of a city as it convulsed from the relative calm of 2004 to the dark days of 2006 and 2007 and settled back into a seething equilibrium in 2008. In January 2005, the streets we flew over were tagged with reminders of that pivotal juncture in Iraq. Colorful election posters and banners with flashy Arabic text hung alongside wanted posters for Zarqawi, with tip-line phone numbers running below his cold face staring out under a black kufi.

Since taking over, George Casey's two strategic priorities had been to build up Iraq's security forces and to support the emergence of a legitimate government. According to this plan, midwifing a new Iraqi government required that Casey secure the three Iraqi votes scheduled that year: in January to elect an assembly to draft the permanent constitution, in October to ratify that constitution, and again in December to vote for the government that would serve under that constitution.

We were increasingly focused on integrating our efforts with the larger MNF-I objectives. So in the lead-up to the January 30, 2005, election, we were doing everything we could to contain Al Qaeda's plans to undermine themâwhich Zarqawi announced a week before the election. On January 23, Zarqawi released an audiotape

calling democracy heresy. Eight years earlier, while the two were locked away together in Jordan's Suwaqah Prison, Abu Mohammad al-Maqdisi, a leading ideologue of the jihadist movement, had

mentored a younger Zarqawi. Maqdisi made his name in the 1990s, in part through an innovative treatise that argued democracy constituted not just a separate political process but a religion unto itself. For true believers, then, voting was a veritable act of heresy.

Zarqawi now invoked this logic as religious top cover for what were surely more clear-eyed strategic concerns. His sectarian scheme relied on keeping Sunnis paranoid and fighting. This wasn't hard: Whether or not Sunnis voted, the elections were going to entrench the majority Shia in power in Baghdad. But Zarqawi needed Sunnis fully disenfranchisedâto make the specter of Shia domination more fearsome and to prevent insurgents from getting the idea that integrating into the political process might have its benefits. So, joined by

other hard-line insurgent groups, Al Qaeda in Iraq prepared to unleash hell on the polling sites and the vulnerable queues of Iraqi voters. Its online warning that week was ominousâand essentially an admission that Zarqawi would target Sunnis. “Take care not to go near the centers of heresy and abomination . . . the election booths,” it threatened. “

The martyrs' wedding is at hand.”

Violence on election day was far more muted than Zarqawi's histrionics portended. Insurgents

overran no election sites. But their threats were enough to keep many Sunnis home; others boycotted in genuine protest of the new government, which would

freeze them into a minority role. Only 3,775 people voted in all of Anbar Provinceâ

2 percent of the population. Sunnis

secured a mere 17 of the new National Assembly's 275 seats.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â *

W

ithin the military, the elections had crystallized the increasing competition over resources, which had grown more acute that winter. The conventional forces understandably sought to employ intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft, like UAVs, to monitor polling sites in the days preceding the vote. We had asked for control of these assets in order to ramp up an offensive effort to preempt AQI's attacks. We sought a balanced approach of using the ISR to pressure AQI's network up until the day before the elections, then shifting them to monitor the voting areas.

Although not the first occasion for passionate competition between special and conventional operations over select resources like ISR, the January elections foreshadowed an extended debate over the best use of what were always scarce, highly useful tools. For relatively new assets, like the Predator UAV, demand continued to soar as more units identified valid, innovative ways to employ them.